I read The Argonauts by Maggie Nelson when I was pregnant with our first child. I read some of it on a roof we used to sit out on when it was warm. It was 2016 and a hot summer in London. You had to clamber out of the kitchen window to get onto the roof. We would sit on the roof to smoke cigarettes and look at the row of bright green poplar trees in front of a housing estate. When I was pregnant, I sat out there to read. Nelson’s incredibly smart and interesting book told me that pregnancy was as wild as I felt it to be and that there was also something intellectually and creatively stimulating about that. This is my favourite bit: “Is there something inherently queer about pregnancy itself, insofar as it profoundly alters one’s “normal” state, and occasions a radical intimacy with—and radical alienation from—one’s body? How can an experience so profoundly strange and wild and transformative also symbolize or enact the ultimate conformity?”

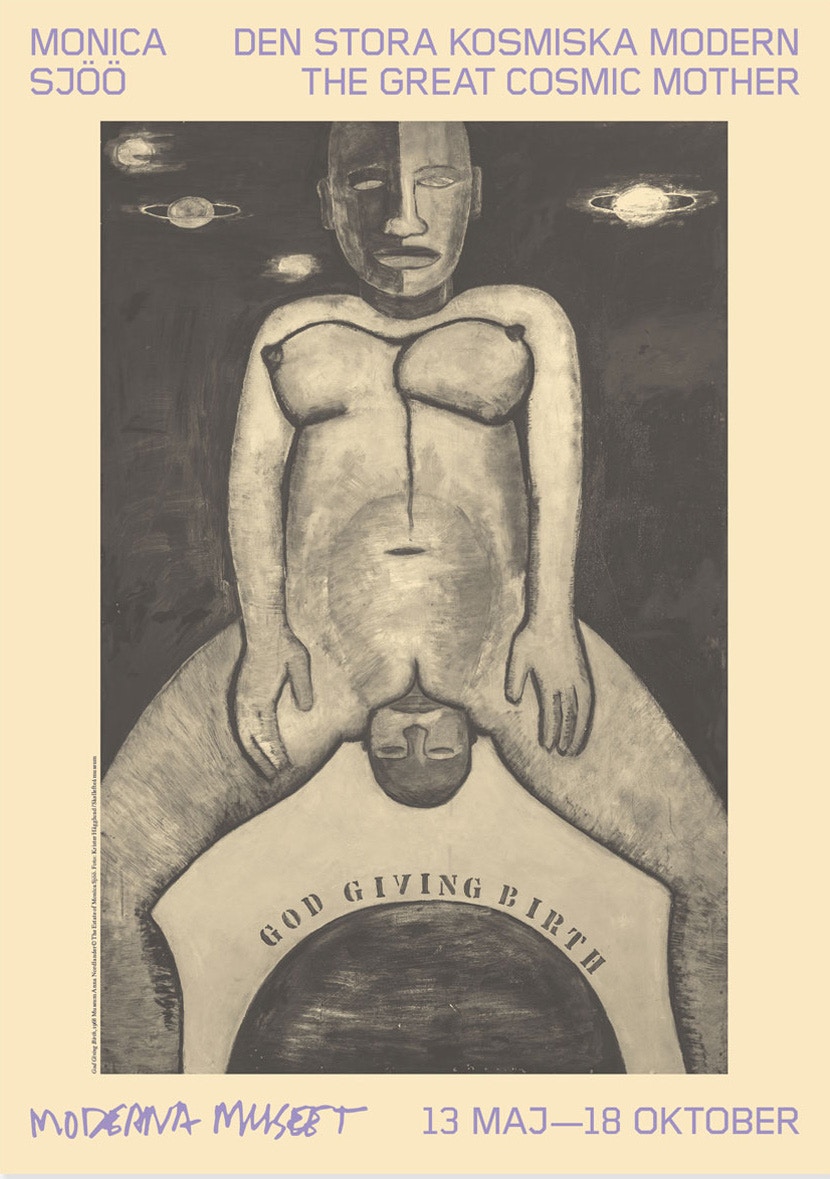

I gave birth three times in a five year period (my youngest is now 3) and each one was quite different. After the birth of my first child in 2016, I was obsessed with wanting to see photographs or depictions of crowning. It just felt so insane to me that a person had made its way out of my body. I don’t feel I’ll ever get over it. One work of art that helped me process this physical, emotional, psychological and existential experience was God Giving Birth by Monica Sjoo. On a really basic level, simply because it depicted birth. Childbirth had been a profound shock in so many ways. It was a kind of final loss of innocence and childhood, for me, and psychedelic, and so paradoxical. Awe // terror // pain // ecstasy. The closest to the sublime I’ll ever be, I’m sure. But yet my culture disavows and hides the realities of birth and the vulnerability surrounding it for mother / birthing person and baby in so many ways. Sjoo, who was a Swedish-born artist, political activist and anarchist, was radicalised by her experiences of birth, especially a home birth with her son in 1961 in which she “saw” the Goddess of the Universe and began to question patriarchal cultures and religions which diminish women. These are her own words about it:

“I wanted to create a painting that would express my emerging religious belief in the Great Mother as the Matrix of cosmic creation. I didn’t want Her to be a white woman. As a result of this work I was nearly taken to Court and my painting was censured many times during the 70s and 80s It was considered “ugly”, “obscene” and “blasphemous”. A modem day witch-hunt was carried out against me and my work. It was racist also. I didn’t know at the time I did the painting that the entire human race is thought to have originated from one or a handful of African women in the mists of time. This has been traced through the mitochondrial DNA which is only carried through the mothers/women. In 1968 there was also no women’s arts movement or a Goddess movement and I felt totally alone. I had a sense though that ancient women, who coincide with us in another time-space, were communicating with and through me.”

She died in 2005. I saw the painting in relief earlier this year in Oxford, England. It was so strong and powerful and bold. For the same reasons, I love Judy Chicago’s Birth Project.

I’ve read a lot of books about the maternal experience over the last years. But before I devoured Adrienne Rich’s Of Woman Born, Maternal Thinking by Sara Ruddick, A Life’s Work by Rachel Cusk and so on, I found solace in Kafka’s The Metamorphosis in those tiny snatches of time. In the early months and years of motherhood I identified with the travelling salesman Gregor Samsa who turns into a gigantic insect, or cockroach, overnight. The transformation happens quickly and unexpectedly. He is trapped in his new body, in the four walls of his room, and he is isolated from his family and wider community. What an allegory for the modern institution of motherhood in patriarchal neoliberal capitalism. What has happened to me, he asks himself, trying to make sense of the transformation. I felt that weird, for quite a while. I felt I had gone. What has happened to me? What has happened to me? It helped when I read the word “matrescence” in an article by Alexandra Sacks in the New York Times and learned that matrescence, becoming a mother, is a significant developmental stage and transition that our culture has neglected or forgotten about and we might all feel like gigantic insects for a while.

Liz Berry is one of England’s finest poets and this incredible poem blew my heart wide open when I read it in early motherhood and then put it back together with kindness and care. It is so beautiful and tender and still gives me goosebumps. I was lucky to hear Berry read the poem at the recent Matrescence Festival in England and it was such a moving experience. I don’t cry much at the moment but I lost it at:

“..I knelt instead

and prayed in the chapel of Motherhood, prayed

for that whole wild fucking queendom,

its sorrow, its unbearable skinless beauty..”

I became obsessed over the last few years with slime molds. They are exquisitely beautiful, intricate, complex beings - tiny, hard to find, but everywhere. Some resemble iridescent ingots of petroleum, others corn dogs made of peach glass, balloons of lip gloss on black stilts, pink foam dissolving into sherbet, licorice buttons with a hundred spider legs. Myxomycetes— the scientific name for slime molds— are fungus- like organisms. Part of their life cycle is spent as fruiting bodies that can look a little like minuscule mushrooms, and they live anywhere there is organic matter: decaying logs, sticks, leaf litter, dung.

They undergo a very dramatic metamorphosis - from an often yellow slime-like slick of plasmodium which moves and predates, anticipates and learns (but without a brain) to these incredible colonies of beauty. They are also hidden. When it felt like my culture was telling me to “bounce back” from having a child and go back to what I was before, which seemed impossible, I found a lot of resonance in slime moulds in early motherhood.

Spread the Jelly suggested a song and an album but one of the disconcerting changes of motherhood for me was that having been obsessed with music my entire life, I stopped being interested or even really listening to it. I weirdly lost the love of it for a couple of years. Everything I listened to sounded alien, I couldn’t connect. But then a few songs started to touch the sides and one was "Les Fleurs" by Minnie Riperton. I listened to it a lot while in labour with my second child.

Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer is one of my favourite books of all time. I don’t usually read books multiple times but this one is different. It’s a text that is so alive, and changes at each stage of life. There’s a part in a chapter called A Mother’s Work which I find so powerful in soothing my premonitory sorrow about my babies leaving home one day, and the inevitable ordinary heartbreak of motherhood, which is change, which is also loss, every day, as the child changes so rapidly. It’s a meditation on Hydrodictyon, a water net of green algae. Inside each of the net cells, Kimmerer tells us, “daughter cells are born”. And then, “in order to disperse her young, the mother cell must disintegrate, freeing the daughter cells into the water”.

“Mothering is like that, a net of living threads to lovingly encircle what it cannot possibly hold, what will eventually move through it,” she writes. Oof.

I was amazed by how relevant Of Woman Born was, forty-something years after it was first published. She had her children in the 1950s, and published the book in the 1970s. It shocked me to realize that the leading assumption I held about motherhood was identical to Rich’s:

“That a “natural” mother is a person without further identity, one who can find her chief gratification in being all day with small children, living at a pace tuned to theirs; that the isolation of mothers and children together in the home must be taken for granted; that maternal love is, and should be, quite literally selfless.”

I found her concept of the “institution of motherhood,” so useful in helping me deconstruct the patriarchal maternal ideal and work out my own way of being a mother. Rich showed how wider societal conditions—in a word, patriarchy—had turned motherhood into a “modern institution,” with its own rules, strictures and social expectations. She made clear that it was the sociocultural institution of motherhood, not the children themselves, that oppressed women and could even mutilate the relationship between mother and child. The institution fostered the idea that women are born with a “natural” maternal “instinct” rather than needing to develop knowledge and skills as caregivers. The uneven power relations between mother and child were, she argued, a reflection of power dynamics in society. It was a setup, in which mothers were destined to fail.

This extraordinary book gave me permission to critique and analyse the systems of modern motherhood which make up a part of my book Matrescence.