My first pregnancy was a lot. I had a routine ultrasound at seven months that turned out to be not so routine. My baby was sticking his tongue out during the exam, which I thought was adorable until the doctor arrived and explained that a protruding tongue can signal a genetic abnormality. I spent the next four weeks in a kind of diagnostic hell. I had an amniocentesis, a fetal MRI, and a four-week wait for the exhaustive genetic testing of my baby’s cells. He ended up being diagnosed with a rare overgrowth disorder called Beckwith-Wiedemann Syndrome, which causes (among other things) babies' tongues to grow very large. Every pregnancy book, every advice app, every ethereal Instagram ad I had consumed during my pregnancy seemed no longer to apply to me. One day, after an OB appointment in Manhattan, my husband took me to Central Park, where I stared into a pond for a really long time. Slick little turtles paddled about. I tossed some leaves in there. Finally the craggy, mossy back of a much larger turtle surfaced from the deep. It lifted its gargantuan head above the water and I looked it in the eye. I googled “really big turtle central park” afterward. It gave me something else to think about.

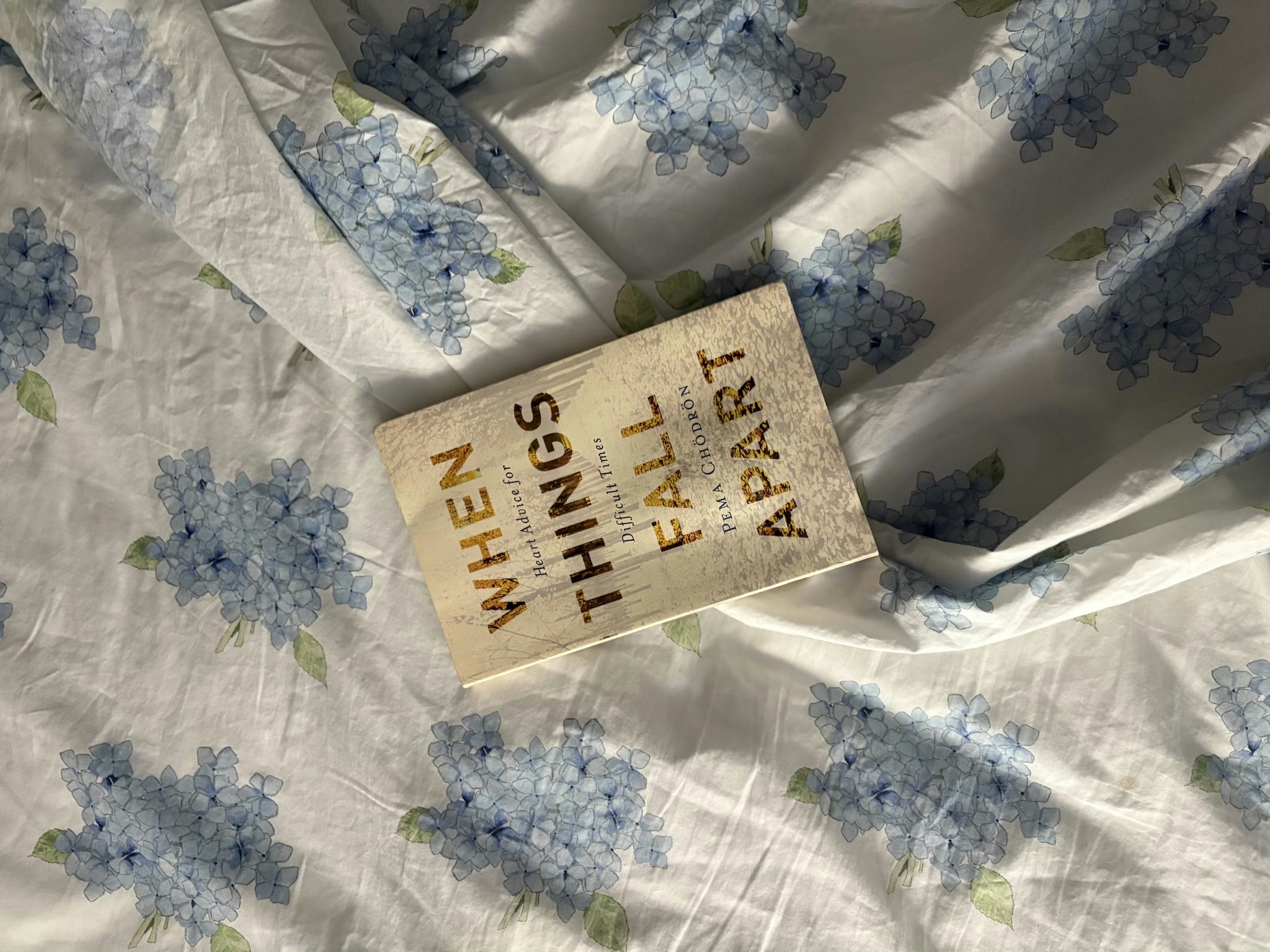

As soon as I told my dear friend Michelle that I had had a troubling ultrasound, she sent me “When Things Fall Apart” by the Tibetan Buddhist nun Pema Chödrön. When it arrived I found its presence in my apartment somewhat horrifying. The ultrasound had led me away from the shelf of pregnancy books featuring photos of smiling women hugging their bumps, and toward the shelf of self-help books featuring oversaturated photographs of bare trees. That’s how hopeless my pregnancy had become: winter-forest-stock-image level of hopelessness. Then I opened it and found the perspective that all other pregnancy literature had failed to offer me. It wasn’t about what I should eat or how I should move but how I could confront myself and my greatest fears. I was growing a human being, and now I had the precious opportunity to become more human myself.

One of my stupidest online habits is to take a photograph of myself, upload it to Facetune, and then smooth, nip and reshape my body and face until I realize that I have made myself grotesque and unrecognizable. For some reason, this makes me more comfortable posting the original photograph; it beats the alternative. During my pregnancy, when my body already felt grotesque and unrecognizable, I took my Facetune habit to extremes, manipulating my body until it looked un-pregnant, then ultra-pregnant, then ultra-pregnant and made up to resemble a Megan Fox Halloween mask. I got a perverse thrill from this, because a) pregnancy is very boring, and b) it allowed me to take digital control of my pregnant image, which had been so commodified, surveilled and morally charged that it seemed no longer to belong to me. My pregnant body itself was unruly and weird as hell, and these pictures worked to visualize all of those contradictions.

"Every pregnancy book, every advice app, every ethereal Instagram ad I had consumed during my pregnancy seemed no longer to apply to me."

I was pregnant in 2020 so I spent a lot of time sitting around and prodding at screens. The best thing I did on them was open Google Maps and “walk” the route from my elementary school to my childhood home in Spokane, Washington. I had not lived in the city for more than 20 years but I could still navigate the path from memory. It was more challenging than I realized: It was over two miles long, led up a winding hill where the sidewalk narrowed then dissolved, and cut across the wooded area of a vast park. Midway through, I would pass my best friend’s house, where he would peel off and I would continue home alone. Retracing my steps through Google Maps and proceeding in its slow and halting rhythm reminded me that I was strong, I could do hard things, and I could always find my way home.

My friend Martha suggested that I put a comfort object in my hospital go-bag, and I’m so glad I did. I brought my childhood lovey, “Guck,” a sunshine-yellow Gund duck from the 1970s with graying fur and a tattered gingham ribbon around its neck. I ended up clinging to it for dear life as I “recovered” from pregnancy, labor and a C-section while struggling to breastfeed a baby in the NICU with an extra-large tongue—probably the most uncomfortable I’ve ever been. The lovey says: You just had a baby, but you also are a baby.

I bought this classic book of feminist sociology a couple of months after my son was born. Its author, Rayna Rapp, underwent an amniocentesis in 1983 that produced a diagnosis of Down Syndrome. She aborted the pregnancy, then spent the next 15 years studying the influence of genetic testing on pregnant women’s lives and everyone else’s, too. Rapp describes prenatal testing as having “simultaneously eugenic and liberating agendas,” which describes so perfectly the ethical plank that I walked in pregnancy. The developing technology, she says, has turned women into “moral pioneers,” who are “forced to judge the quality of their own fetuses,” thus “making concrete and embodied decisions about the standards for entry into the human community.” Amid my prenatal diagnostic journey, a doctor looked at my baby’s brain on an ultrasound screen and told me that it looked as if it may be severely underdeveloped; one week later, an MRI revealed that his brain was, in fact, developing normally. I asked myself so many questions in that week of waiting — about abortion and disability, but also the frustrating limits of scientific knowledge, and the elusive purpose of life itself — that stuck with me even after the MRI provided its medical answers. Rapp’s book was the first source I found that acknowledged that pregnancy was, among other things, a profound ethical and philosophical experience.

AMANDA HESS is a critic at large for The New York Times. She writes about internet and pop culture for the Culture section and contributes regularly to The New York Times Magazine.Her debut book, Second Life: Having a Child in the Digital Age, is both a timely memoir and investigation into the convergence of technology and parenthood.