The existential business of sleep

Words by Leah Bhabha

“Just close your eyes, your body knows what to do.” It’s 7:06 p.m. and Matilda and I are in her room. The books have been read, the unicorn nightgown is on, the teeth are brushed, the socks have been put on and taken off, the water bottle refilled, pees attempted, covers re-tucked. She’s restless, kicking her legs around in bed, her dark hair splayed on the sheets, a tendril over Belle, one on Ariel, another covering Jasmine. (I’ve never liked Disney and now my life is ruled by their royalty). “Just close your eyes, your body knows what to do.” I can tell she’s trying to calm herself, and I repeat the phrase again, as much for me as for her. I inhale slowly, trying to still myself in this nightly ritual, one that’s been setting flares of anxiety off in my chest lately.

We’re in the house we moved into a few months ago. Sleep for my four-year-old has become fraught. We spent her first three years in Brooklyn, then ten months living with my parents in Cambridge, MA, and in late spring, moved into our own home, thirty minutes from her grandparents. With the maelstrom of transitions she’s undergone—leaving her place of birth and first friends, starting camp then preschool, sharing her family with a younger sister born days after she turned three—I had expected disruptions. But her sleep wasn’t affected. Now, months later, in a new place away from her doting grandparents, coupled with larger looming existential fears, the awareness that blooms with age, and the freedom of a ‘big girl bed’ without barriers, we’ve experienced lengthy, emotional bedtimes, multiple night wakings, and very early mornings.

The fear began a few weeks before the move. In “her” old room (my mother’s converted office) she became hysterical one night, rocketing out of her crib. Other than small blips here and there, she’d been a solid sleeper for years. Her nighttime routine had been swift and simple. We sleep trained early and stuck rigidly to The Schedule, determined that rest above all else would prevail. It was a safety net—a framework by which to chart our days, amidst the meltdowns and snack demands, the eye-wateringly tender moments and the exasperating ones. 7pm. That was it.

"We sleep trained early and stuck rigidly to The Schedule, determined that rest above all else would prevail. It was a safety net—a framework by which to chart our days, amidst the meltdowns and snack demands, the eye-wateringly tender moments and the exasperating ones. 7pm. That was it."

Sleep means separation and it threatens us with loneliness. At 37, I still struggle with the solitariness that comes with darkness, the feeling that everyone else is resting and I have only 5,4,3 hours left until I have to get up. The elements of life that we eject from our consciousness in the daytime, when immediate needs and calls and interactions insert themselves, become outsized in the quietness of the night. When I tell my little girl her body “knows what to do,” it doesn’t feel entirely truthful. Because, so often, my body doesn’t, no matter how many times I flip the pillow or get up to pee. “You don’t want to be enmeshed,” my therapist says. She has to move through these things just l do, she reminds me. Resilience.

When Matilda told me that she was nervous about the new house and didn’t want to be alone, we talked over and over about change and togetherness. We read and reread The Invisible String, played hide-and-seek—anything to reinforce the fact that connection can remain despite physical separation. Because my husband and I were so ready for our own home, one apart from my parents, I couldn’t imagine how deeply she wanted to stay. For months, I’d worked in my high school bedroom, at the desk where I’d done physics homework, next to the bookcase lined with diaries scribbled in Gelly Roll pens, burned CDs, and photo albums of friends I hadn’t thought about in decades. A mausoleum to my teenage self. The room was also where the baby slept and where my parents exercised. For naps and workouts, I relocated my calls (often after they’d already started). My husband and I were eternally grateful for my parents’ generosity and love—privileged to have the space for our entire family to stay—but I began to chafe under the confines of personal history and shared living. Being there also put my parenting in sharp relief, trapping me in a version of myself that was equal parts postpartum hormones, bratty angst, and exhaustion. My parents were so warm, so happy with our intergenerational existence, which added guilt to the cocktail of emotions. When Matilda said to me, one night, after hours of soothing and stories, “I just feel tricky about the new house and about leaving,” I couldn’t relate.

"At 37, I still struggle with the solitariness that comes with darkness, the feeling that everyone else is resting and I have only 5,4,3 hours left until I have to get up. The elements of life that we eject from our consciousness in the daytime, when immediate needs and calls and interactions insert themselves, become outsized in the quietness of the night."

Her sparkly curiosity, her ability to access and express her feelings, her sensitivity—these qualities I adore about my daughter make it only harder to see her working through this. She can name her worries and yet I sometimes feel powerless to assuage them. The confines of her crib, in a house she knew, were a salve that created more challenges once taken away. Like a good millennial, I scour the internet for solutions, often asking the same question over and over and hoping for a different answer—the definition of insanity, they say. Searching has become a maddening sort of comfort, to know how common preschool sleep challenges are and also to distract my impatient self from the buried knowledge that yes, this is a phase that will end, and no, nothing will suddenly change it. I know it’s a blip on the radar of childrearing, a garden variety difficulty compared to so many others, to children growing up in bombed out neighborhoods and homes without food. It engenders more guilt, of course, that this is my current cross to bear.

And yet, still I search. “3.75 year old sleep regression how long.” “Toddler night wakings” ”sleep anxiety 4 year old” “Toddler bed bad in new house move.” I’ve watched modules, read and reread chapters of sleep books, consulted scripts from online specialists, and asked questions in forums. I write myself notes and parrot things I see on Instagram, mantras devised by smiling women in their bright, beige living rooms. I flit in and out of feeling like my-kid-isn’t-sleeping is becoming my entire personality and replacing the anxiety of a new home, a new life, a world on fire, and professional frustrations with her sleep struggles.

When this all began, the wheels of my own sleep issues showed how ragged and rusty they were, how fraught with memories of being picked up from sleepovers, of nights awake til dawn, of the half-used bottles of melatonin and magnesium, dream journals, and weighted blankets. Where the silver bullets have failed for me, I need them to work for her. Color-changing nightlights, meditation books before bed, a shirt that smells like me, sticker charts, plastic princess figurines in the morning as rewards—anything. I’ve overthought each change, each addition or subtraction from her routine. All I want is for her to have the relationship with sleep that I’ve never had.

***

" I’ve watched modules, read and reread chapters of sleep books, consulted scripts from online specialists, and asked questions in forums. I write myself notes and parrot things I see on Instagram, mantras devised by smiling women in their bright, beige living rooms. I flit in and out of feeling like my-kid-isn’t-sleeping is becoming my entire personality and replacing the anxiety of a new home, a new life, a world on fire, and professional frustrations with her sleep struggles."

When I was a child and couldn’t fall asleep, which was often, I would travel with my mind. We moved often when I was growing up, and I used past ‘homes’ to distract me from insomnia. From the pink sheets of my trundle bed in Chicago, I’d transport myself to the London room I slept in until I was six, before we moved to the U.S. Eyelids closed tightly, I’d envision the yolky glow of streetlights through the curtains and the vague shouts and late night whoops emanating from the park in front of our flat. With each passing year in America, I could picture our London home, neighborhood, and English friends less and less, but my body could always recall the feeling of the bed beneath me, the proximity to my brothers’ and parents’ rooms, and, if I tried hard enough, the scent of London dampness mingling with cooking smells that never fully ventilated after dinner.

If a visit over the Atlantic didn’t calm me, I might venture further, skating over the continents Eastward, to my father’s childhood bedroom in Mumbai, which I shared with my brothers on holiday trips, my head under a sheet to avoid mosquitos. Wherever my imagination had carried me, I would be lying with my ear pressed tightly on the pillow to drown out any noise. In my twenties, I continued my midnight voyages, quieting the East Village revelers or sanitation trucks with memories of past apartments, old beds, and sheets long since discarded.

***

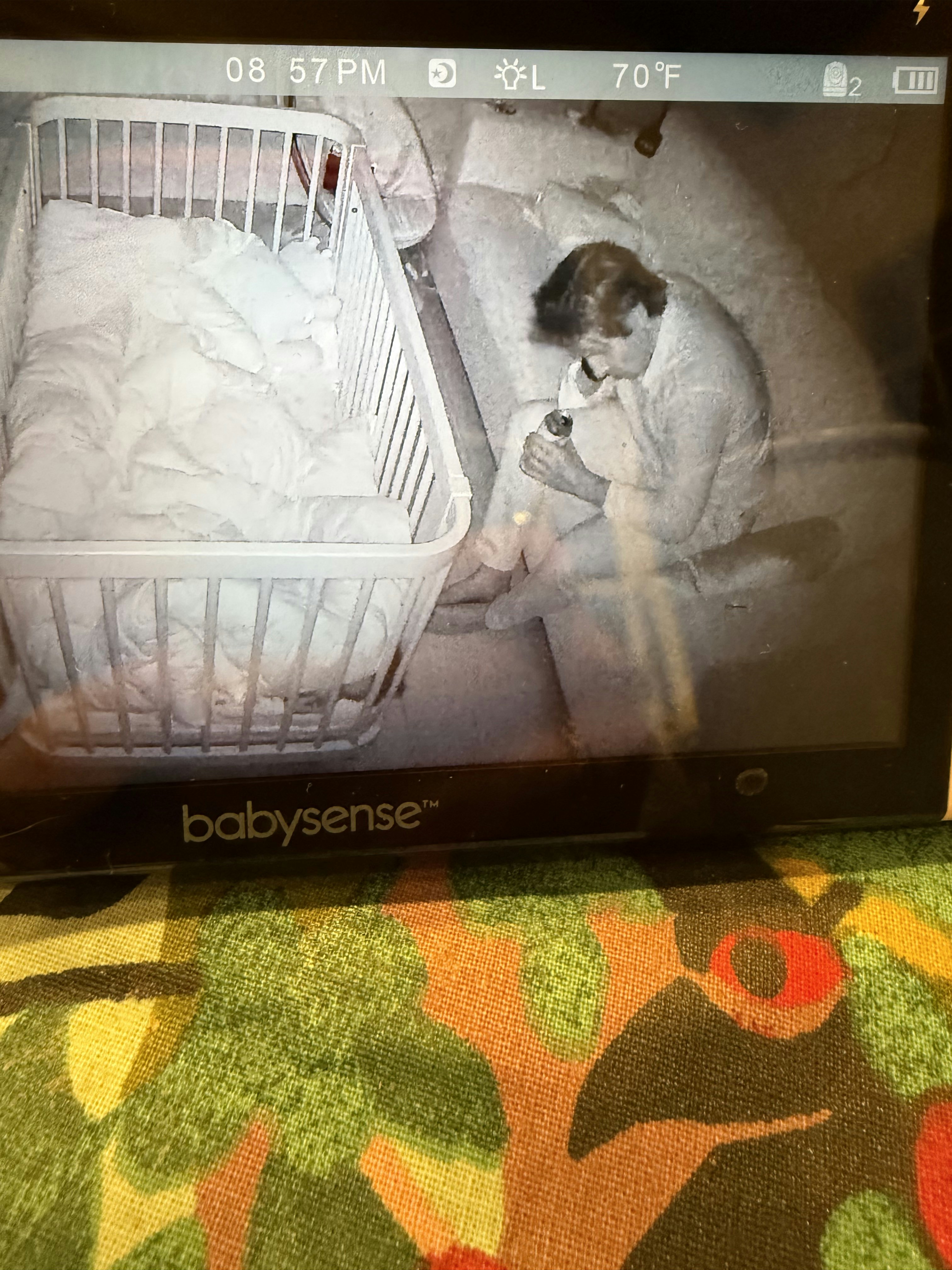

Diving deeper into the roots of Matilda’s sleep difficulties, I realized there had been kernels of worry months before the move had been on the horizon. I had enacted such a quick bedtime routine that she would often call out to me right after I’d closed the door, repeating the same run-on sentence over and over “Get me in the morning don’t let daddy talk through the camera don’t take a shower.” Said all in one breath, repeated as a sort of mantra—a way, I think, to get me to stay in the room, to connect, and assure her that I’d be nearby. She didn’t want me to take a shower because to her, that was a physical separation. She didn’t want Daddy to talk through the monitor camera because, frankly, it scared her when she was already feeling alone. She wanted me to wake her up so she was assured she would see me first thing, the conclusion of 12 hours apart. A few weeks after we moved in, I went on a mother’s day friends' trip to Mexico. For weeks after, she’d ask, whenever I left the house, if I was returning to Mexico. I felt trapped, wanting to go out with friends at night, but knowing that the inevitable bedtime dance would thwart any such independence.

During these months, I’ve been so fearful of her need for me at night, even though her need for me is a thrumming heartbeat of our connection. The push/pull of separation, of knowing I’m a part of her emotional core, carries with it a weighted blanket that is simultaneously smothering and soul-filling. Partly because of my own fear of exhaustion and partly because of my desire to foster her independence, I’ve always tried to maintain separation at night, erecting boundaries that give me a sense of control and calm. Snuggles always, co-sleeping never. She’s grappling with the complexities of dependence and independence while managing a desire for togetherness—”How can I know we’re together if you’re not with me?” she asks. And lately, she’s preoccupied with death—developmentally appropriate for preschoolers—but jarring nonetheless. Recently, a friend said to me, “Maybe sleep isn’t even what she’s working on right now. It’s just manifesting that way.” And I know, of course, that sleep challenges are an amalgamation of so many other concepts she’s processing—control, attachment, boundaries, triggers, loneliness—and represent an urge to be held literally and metaphorically. She can recognize basic physical needs like hunger, bathroom, and sleep, but still requires someone she trusts to help her fulfill them. The more Matilda knows who she is, the more aware and her own person she is, the more she acknowledges her free will coupled with her need. They need us from day one, but they can only articulate, and realize it, later.

***

Parenting has brought out in me much that I expected—a maternal instinct I’ve always had, a willingness to be goofy, a warmth I associate with closeness—and much I didn’t—a sense of patience, a sometimes obsessive need to adhere to schedule that often sparks more anxiety, and a constant need to problem solve even when there is no solve, merely time. Some aspects of mothering feel so second nature, and some keep me second guessing, “Am I doing this right?” “Will what’s happening right now be forever?” “Will I fuck her up?” The answers are who knows, definitely not, and yes, but that’s okay because it’s part of the experience. I know all of this, and yet I still feel the intensity of these whirring unknowns. With the constant metamorphoses of these small people, who change opinions and develop skills seemingly overnight, we ground ourselves in the knowledge of who they are, even if it’s ever evolving. “She’s a great sleeper,” my husband and I said smugly for years. “She’s super outgoing,” “She eats anything.” But then, of course, there are the shy phases (developmentally and evolutionarily appropriate) and the picky eating phases (exerting control). These constant changes, which shift as soon as you’ve become comfortable with them, have been one of the most challenging but enlightening parts of motherhood.

***

"“She’s a great sleeper,” my husband and I said smugly for years. “She’s super outgoing,” “She eats anything.” But then, of course, there are the shy phases (developmentally and evolutionarily appropriate) and the picky eating phases (exerting control). These constant changes, which shift as soon as you’ve become comfortable with them, have been one of the most challenging but enlightening parts of motherhood."

There’s a desire to wrap things up in a bow, neatly package a narrative, especially a personal one, with a beginning, a middle, and an end. There’s also the complexity of writing about something when you’re in it, of taking notes on what gives you pause and of overthinking moments even further in the service of a creative outlet. But as a writer, I’ve always leaned on narrative as a way to comprehend life, so why would this moment be any different? With a few weeks of regular check-ins, her door opened and closed so many times that the handle started to squeak. Bedtime has mostly eased although, of course, nothing is linear and we still have nights of her little contorted face wondering earnestly, in tears, why she can’t just sleep in bed with me. “Because none of us will sleep well, my love” doesn’t seem to satisfy her inquiries. The middle of the night wakings are very slowly trending towards the positive, and we had a night of no wakings recently. My hope is that once school starts, sleep will start to resolve. “I’m learning to love staying in bed,” she said to me this morning. I’ve probably talked to her too much about it, unintentionally applied too much pressure, convincing myself that if I could just understand exactly how to fix the problem while maintaining boundaries, it will all go back to ‘normal.’ So I’m working on trying to dispel the urge to problem solve and to look outside for answers, trying to let her work through what she needs with less of my input and even more of my patience. I’m trying to really, truly slow down and let go. Life doesn’t consistently adhere to one’s expectations and schedules, so why would anything else? Particularly a child in constant discovery, with a fledgling sense of emotional regulation. Recently, as I’m going to sleep, I’ve started to tell myself “There’s nothing you have to figure out right now, nothing left to solve for the day.” It’s a privilege, of course, to know that outside of the quotidian difficulties and uncertainties of adult life, I can will myself to relax. My body might not know what to do, but I’m hoping that it will learn, right alongside Matilda’s.

Leah Bhabha is a writer and content strategist who has written for publications like Vogue, New York, The Financial Times, and Bon Appétit. A graduate of Columbia’s MFA program and cookbook co-author/recipe tester, she’s currently consulting for a variety of brands and working on a memoir about her family and its global roots. She lives in Concord, Massachusetts (after 12+ years in NYC, and London, Chicago, and SF before that) with her husband, daughters Matilda and Rio, and dachshund, Strudel.