Getting Sticky With Gianna Toboni

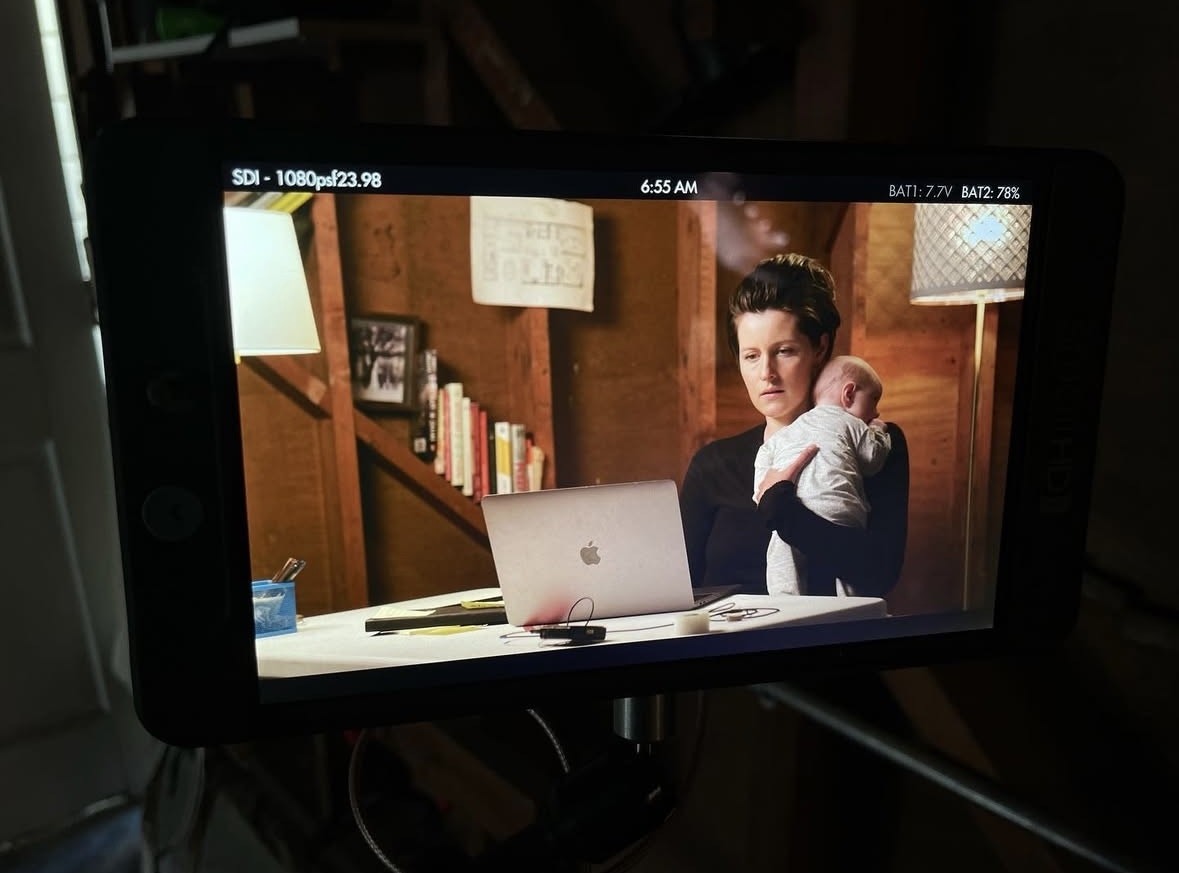

Photos by Maria del Rio, Words by AnaMaria Glavan

“I think you’re like a police officer who writes books because you go to jails a lot.”

That’s how Emmy-winning journalist and documentary filmmaker Gianna Toboni’s young son explains her work. “Not quite, but also not a bad guess,” she laughs.

The accolades for Toboni’s reporting are both extensive and well earned. Over the course of her career, she has tackled an extraordinary range of subjects, all with the aim of educating viewers and helping them distinguish fact from fiction. Much of her work lives in the gray areas: hero versus villain versus anti-hero, peeling back assumptions and demystifying stories audiences often arrive at with firm opinions already in place.

Her documentary Just Kids, which explores the lives of trans youth and what gender-affirming care looks like in the midst of state-level bans, is a clear example: piece by piece, she unearthed data that challenged the talking points of conservative politics. Her book The Volunteer, chronicling inmate Scott Dozier’s path to death row, follows a similar thread. Now, she hopes to continue that work alongside her sister, actress Jacqueline Toboni, through their new venture—an aptly named production company called Mother Media.

Below, Gianna reflects on what it’s like to sit knee-to-knee with someone on death row and then return home to make mac and cheese for her family, and the challenge of explaining a more nuanced version of a villain to her young son.

“I ended up really loving the C-section”

When I was pregnant with my first, we found out he was breech and I’d need a C-section. I struggled with the news at first; eventually I felt grateful for the medical advancements that keep moms and babies safe when things don’t go to plan.

I ended up really loving the C-section. I thought there was something kind of beautiful about all of the orchestration; the team of medical personnel assembling around us for the procedure, all experts in their own area. And you also get to plan! I threw a party for friends the night before, baked cookies that morning, took the ferry to the hospital in this very calm way. And those first two weeks of being a parent were the greatest two weeks of my life, and I knew I’d never experience anything like it again. It was pure magic.

At the same time, in the months after, there was this voice in my head: You have to stay on your shit. You have to keep working or you’ll miss out on opportunities. I remember calling women I admired who were a decade ahead of me in their careers, asking whether I should skip a trip that involved risk. They told me, Don’t go. It won’t matter for your career. What matters is your health and your baby’s health. That advice was huge in helping me let go of the guilt. I’m so grateful for their perspective.

The internal conflict between being a mother and being a journalist isn’t easy to disentangle. The truth is, I never loved the dangerous part of the work, and I’m no longer seeking assignments that keep me on the road. I love a Tuesday afternoon when I can make mac and cheese and talk about superheroes at home.

That said: I still do work that most people would consider dangerous. I still go to death row, and I still sit knee-to-knee with people convicted of homicide. The reason I got into this work in the first place is because I believe in holding power to account, and that north star has remained unchanged. I also believe in elevating the voices of people who otherwise wouldn’t have their stories told, or their injustices acknowledged. That’s still the core of what I do.

"I ended up really loving the C-section. I thought there was something kind of beautiful about all of the orchestration; the team of medical personnel assembling around us for the procedure, all experts in their own area. And you also get to plan! I threw a party for friends the night before, baked cookies that morning, took the ferry to the hospital in this very calm way."

A decades-long battle: Blatant propaganda for political gain

More than 10 years ago, I started spending time with trans kids, their families, and their doctors to try and understand what gender-affirming care was. I’ll admit—I was nervous going into it. I didn’t love the idea of hormones and kids because I simply didn’t understand it. But then I spent real time with these kids, followed them as they grew up, interviewed their doctors, sat in hospital rooms while they got care.

I asked doctors to see datasets, to understand the evidence behind the care they were recommending. And what I found was the real truth of this hotly contested political issue, which could not have been more different from what I was seeing on the news or hearing from conservative politicians. It felt so insane to be experiencing the reality up close—and studying it deeply—while watching blatant misinformation being spread for political gain. So I just kept going. We ended up producing eight documentaries on trans youth over the last 10 years.

I want to show that these are kids trying to live a normal life. They don’t have a political cause. They’re not advocates. They just want to go to school, grab McDonald’s, hang out with friends, and be accepted. They’re also mature, articulate, and unwavering in who they are over years of knowing them. Their clarity about their identity is striking.

"I asked doctors to see datasets, to understand the evidence behind the care they were recommending. And what I found was the real truth of this hotly contested political issue, which could not have been more different from what I was seeing on the news or hearing from conservative politicians. It felt so insane to be experiencing the reality up close—and studying it deeply—while watching blatant misinformation being spread for political gain."

I went back and looked at the historical context of these political attacks. The language used against trans kids today is mirrored from the language used against gay men in the ’70s. “Save our children.” “Protect our children.” It’s the exact same script, and it still works, politically, for the right. These kids and their families have become so villainized in the media.

My number one message right now is that this is a parents’ rights issue, and it is government overreach. Families and doctors should be the ones deciding what’s best for a child; not politicians. When you frame it that way, it resonates more, even with people who don’t instinctively understand the issue.

My goal is to educate. I remember being in rural Indiana, a very conservative county, and a man in law enforcement came up to me and said he recognized me from the documentary I did on trans kids. He told me, My wife and I are very Christian, very conservative, and we’ve been anti-trans for years. But after watching your film, it opened our minds to what these families are actually dealing with. Encounters like that remind me how important this work is.

On the parents’ side, what’s been fascinating is seeing this cut across every political and religious line. Liberal, conservative, evangelical, Jewish. When their kid comes out, almost every parent goes through the same script: initial rejection, denial, and then eventual acceptance. They realize that the only way for their child to be healthy is to embrace who they are. No parent I’ve ever interviewed chose this journey. It’s hard. But they show incredible strength by continuing forward for the sake of their kids.

"My number one message right now is that this is a parents’ rights issue, and it is government overreach. Families and doctors should be the ones deciding what’s best for a child; not politicians. When you frame it that way, it resonates more, even with people who don’t instinctively understand the issue. "

Unchecked algorithms are antithetical to a healthy democracy

My book, The Volunteer, is a story that began in 2017 when I met a man named Scott Dozier who was scheduled for execution in Nevada. I was making a documentary on him for VICE on HBO, and then his execution was stayed. I got to know him very well and I couldn’t shake his memory after he died. I knew his side of the story, because we spoke almost every other day. I knew what the other men on death row were telling me. But I couldn’t get anyone inside the prison to say anything.

I realized I needed the space of a book to fully investigate. Over the course of a year, I filed countless FOIA (Freedom of Information Act) requests and eventually got access to prison officials’ text messages, emails, medical records, internal memos, and phone logs. With all that information, I was able to write a detailed account of what led to his death.

I knew this endeavor would be a professional challenge, but I underestimated the personal challenge. While researching, I realized I had, in some ways, aided Scott Dozier in his pursuit of death without fully recognizing it at the time. Sitting with that realization was confusing and painful, but instead of burying it, I made myself process it.

One of my goals with the book was to shake myself and readers out of our comfort zones. We live in bubbles, algorithms, and echo chambers. It’s not healthy for us, and it’s not healthy for democracy.

I’d always been anti–death penalty, but meeting Scott, someone volunteering for execution, forced me to rethink things. I saw the cell where he spent at least 22 hours a day. He was also placed in even more extreme solitary confinement for weeks at a time. I saw how it degraded him completely. It made me see that incarceration in many American prisons is akin to torture—and that sometimes not being executed can be more cruel than the execution itself.

I started trying to imagine what it must feel like to be a parent who’s lost a child in a school shooting. I’ve thought, If someone killed my child, I’d want to kill them myself. But when I sit with the idea of pursuing the death penalty, I’m not sure it would solve anything. Taking another person’s son off the earth wouldn’t bring mine back. At the end of the day, given how broken the system is, I don’t believe the death penalty should exist.

"One of my goals with the book was to shake myself and readers out of our comfort zones. We live in bubbles, algorithms, and echo chambers. It’s not healthy for us, and it’s not healthy for democracy."

On the importance of prison reform

I’ve met many mothers in prison: some serving short sentences, some on death row who will likely never be released. There are some amazing programs being rolled out in California. I recently watched one mom FaceTime with her daughter, which she does every afternoon, to help with homework. They sat there quietly, working through math problems, the daughter held her paper up to the camera while the mom explained what to check again. It was such an ordinary moment, something most people take for granted. And it had been stripped from her until reforms allowed that connection.

These moments are so formative for kids. Research shows that children who maintain strong bonds with their incarcerated parents are far less likely to end up in prison themselves. That’s why programs like these matter. There’s a big push to expand them, to help incarcerated parents rehabilitate and return to society ready to live productive lives.

"Research shows that children who maintain strong bonds with their incarcerated parents are far less likely to end up in prison themselves. That’s why programs like these matter."

The hero vs. the villain vs. the anti-hero

My kids are still young but they have some sense of what I do. My son is starting to read, and he opened my book and sounded out a curse word on the very first page. He goes: You said s*! The character in the book said sh*t, not me! I asked him what he thought I did for work, and he said, I think you’re like a police officer who writes books because you go to jails a lot. Not quite, but also not a bad guess.

The hardest part of my work to explain to a child is the gray area. For my son, as a five-year-old, the world is full of good guys and bad guys, superheroes and villains. Everything is black and white. But almost nothing is that simple in criminal justice. I try to explain to him that not all bad guys are only bad—they may have done something bad, but there’s often a way for them to become good again. It’s a tricky balance, trying to raise him with compassion and humanity without giving the impression that it’s ever okay to hurt people.

As a parent, I have an extraordinary opportunity to be a good influence on a child. In my work, I’m surrounded by adults who were often failed when they were children. So if there’s one thing I can control, it’s that I show up for my kids. The world feels like it’s on fire, and plenty of people I know are deciding not to have kids because of it. But what I can do in my house, on my block, in my community is important. I keep my optimism by keeping my focus small.

"I try to explain to my son that not all bad guys are only bad—they may have done something bad, but there’s often a way for them to become good again. It’s a tricky balance, trying to raise him with compassion and humanity without giving the impression that it’s ever okay to hurt people."

Chipping away at the zeitgeist, story by story

Recently, my sister and I started a production company called Mother Media. We named it after our mom, who’s the greatest storyteller we know. So much of our childhood was shaped by her stories, whether at bedtime or on long car rides, and this was a way to honor her.

We’re developing both scripted and unscripted projects. Our film Just Kids premiered at Tribeca, and we’re now in development on a celebrity documentary we’re really excited about. It’s not your average celebrity doc. It digs into universal themes like mental health, abuse, and resilience, issues that so many of us are facing today. That’s what we aim to do with every project, whether it’s celebrity, true crime, or sports: find the deeper meaning in the zeitgeisty issues everyone is trying to navigate, and uncover the universal themes that resonate beyond the story.

Storytelling has always been something I’ve loved. I remember watching Lisa Ling and Diane Sawyer and being fascinated by long-form news documentaries. But even outside of journalism, socially, there was always street cred that came with telling a great story. And telling a good story is hard. It’s a craft.

Sometimes stories land, sometimes they don’t. (And honestly, when they don’t is when you learn the most.) Even on the way to dinner with friends, if I know I want to tell a story, I’ll think through it: what’s the act structure, what line will land. There’s nothing better than delivering a story and getting the laughter or whatever reaction you’re hoping for. That feeling is unmatched.

None of my stories are about me, but I hope my kids will understand why I pursued this work. My biggest hope is that they grow up to be good forces in the world—kind, loving, treating others the way they want to be treated. If they can see that in my work and take it with them, I’ll feel like I’ve done my job. As both a journalist and and as a parent.

"None of my stories are about me, but I hope my kids will understand why I pursued this work. My biggest hope is that they grow up to be good forces in the world—kind, loving, treating others the way they want to be treated. If they can see that in my work and take it with them, I’ll feel like I’ve done my job. As both a journalist and and as a parent."