My best friend’s breast milk fed my baby

Words by Sophie Lucido Johnson

Maybe this story begins with a birthing class. To be frank, I hated it.

The class pretended to be progressive and radical, and it was filled with ideas that I generally agreed with: that birth shouldn’t be feared, that bodies are designed to give birth, that birth can and should be an experience directed by the birthing person. The person teaching the class did nothing to hide the fact that she was anti-medical intervention. (That included, among other things, the use of an epidural as pain relief.) She didn’t like OBGYNs, and she didn’t like Prentice, the hospital where we already knew we were going to deliver. The people in the class (except one) all appeared to be white, and we were all people with relative financial resources. The first problem I had with the class was that there was a real “cost shouldn’t be a factor” mentality around birthing that left a bad taste in my mouth.

My least favorite session, however, was the one about breastfeeding. We learned that breastmilk was really the only acceptable food for a baby, that all women can produce enough milk for their babies if they work hard enough, and that the terrible doctors at the hospital will try to pump your baby with formula, so you must be vigilant in never letting your baby out of your sight, lest they be secretly tainted in a sinister back room filled with formula-thrusting ghoul physicians each greedy and under the thumb of Big Formula. (It seems like I’m linguistically exaggerating. I ONLY BARELY AM.)

We watched a video about this. The woman in the video said that we might receive samples of formula in the mail, and that formula was essentially poison, and so we should donate the formula to homeless shelters. (?!.) Although I felt uncomfortable-bordering-on-furious, I nevertheless believed parts of this video. Breast milk was best. I’d heard this from so many trustworthy people, it had to be true.

So, at the hospital, when my baby wouldn’t stop screaming and the doctors offered to give her a little formula to help calm her, I patently refused. This was what the woman had warned us about, and as much as I knew she was horrible, I was also not going to let anyone poison my baby. It helped that my best friend had recently gone through this; she’d seen a lactation specialist. I knew it took a little time and a lot of hard work to get the breast milk to flow, but that in the end, it would flow.

"My least favorite session, however, was the one about breastfeeding. We learned that breastmilk was really the only acceptable food for a baby, that all women can produce enough milk for their babies if they work hard enough, and that the terrible doctors at the hospital will try to pump your baby with formula, so you must be vigilant in never letting your baby out of your sight, lest they be secretly tainted in a sinister back room filled with formula-thrusting ghoul physicians each greedy and under the thumb of Big Formula."

But maybe the story begins earlier. Like, four years earlier, when I met a person named Bethany, whom I thought I would hate — mostly (and I am not proud of this) because her name was Bethany. We shared a classroom at the same public arts high school: she taught history in the morning and I taught writing in the afternoon, and over lunch breaks for a calendar year, we fell madly in love. Ride-or-die, more-than-friends-but-not-romantic love; you know it when you see it. Bethany was married, I was married, and like I said, this wasn’t sexual or romantic: it was the kind of love that women have always fallen into regardless of sexuality since the dawn of time. A year after we met, we moved in together (with our husbands and our pets). We had the perfect number of people in one house for board games, an extra large pizza, and a Christmas tree.

We cohabitated well, and the house felt cozy but not cramped. My husband Luke and I wanted to have a baby and Bethany and her husband Brett wanted to have a baby. So we all, separately, went about trying to get pregnant. Bethany and Brett succeeded first, and Bethany gave birth to their son four and a half months before I gave birth to our daughter. Bethany had had trouble breastfeeding, but ultimately, she conquered it. When I finally went into labor, I knew that an uphill battle was ahead, and I knew what it would take to win. But I was tough, and, crucially, I had an ally. Not only did I have an ally, but she lived in my house.

*

Or maybe the story begins even earlier than that. Maybe it begins thirty-four years earlier, when my own mom got pregnant after her own trials and tribulations with trying. Her fetus developed healthily, and everything was thankfully normal — except, and there was no way for her to know this, and nothing she could have done about it, the fetus lacked sufficient tissue in one area that wouldn’t be evident until years later.

In pregnancy, my breasts didn’t really grow. The rest of me did: I gained 65 pounds and every one of my limbs swelled. There were literally no close-toed women’s shoes that fit on my balloon-animal feet. In November, I stomped around ingloriously in the early Chicago frost wearing velcro-strap sandals that scooped up little bits of ice as I walked. But my breasts stayed basically the same. And they hadn’t really grown when I was in adolescence, either. My nipples grew, but my breasts didn’t. I stuffed my bra all through middle school, figuring that eventually my body would change and I could swap out the stuffing surreptitiously. But when I went to Victoria’s Secret when I was 17 to get fitted for a proper bra, the lady with the measuring tape told me they didn’t have any bras there that were my size, which she described as “not yet a AA cup.” I bought all my bras from the teen girl section of Target, and in my 20s, there emerged a thing called a “bralette” that was a non-bra I could use to flatten my puffy nipples under a shirt, and I bought a ton of them and stopped thinking about it.

I stopped thinking about it until two days after my daughter T was born, when the in-hospital lactation specialist came in to check her nipple latch. She took one look at my breasts and sort of recoiled. I told myself I was imagining this, except then she lightly sneered and said, “So, like, did your breasts grow during pregnancy?” She was the type of lactation specialist who (1) was wearing crystals as more than just jewelry, and (2) said “like” a lot. I told her that they didn’t really grow much. She said, “Oh, OK. Well, like, I can’t really evaluate the situation because, like, she” – she indicated to T – “is screaming so much or whatever. So you can come back, like, tomorrow if you really want an evaluation.” And then she practically ran out of the room. Looking back at this interaction, I should have known that something wasn’t right. I had erroneously chalked the weirdness up to the personality of a person with large crystals.

"In pregnancy, my breasts didn’t really grow. The rest of me did: I gained 65 pounds and every one of my limbs swelled. There were literally no close-toed women’s shoes that fit on my balloon-animal feet."

After we got home, T kept on screaming — a LOT. I knew that babies screamed. I was resilient, and decided the screaming would not affect me. T screamed so loudly that she sounded like a sacrificial goat. She screamed so much that eventually, she lost her voice, and then she dry-screamed pathetic air noises that could make a clinical psychopath feel heart-meltingly sad. When they’d discharged us from the hospital, the pediatrician expressed concern that she’d lost so much weight, but since she had come out big (almost 10 pounds), it worried her a little less, and she let us go, telling us to check in with a pediatrician the next day. When we got to the pediatrician with our wormy, raspy, now-slightly-yellow baby, she gave us a compassionate smile that I recognized: it was the same smile you gave to someone whose heart you knew you were going to have to break.

By this point, two things had happened: the first thing was that T had had several successful-seeming feedings. She was latching, and I could tell. I had read an entire book about breastfeeding (you seriously Do. Not. Sleep. In that first week of parenthood), and I knew that I was doing everything right. The second thing was that Bethany had offered up some of her frozen breast milk. She had a lot of it, because her baby had transferred over to formula and wouldn’t take breast milk anymore. But I didn’t know if it was OK to give my baby another person’s breast milk, and so I decided we’d wait until we saw a doctor, and then maybe I’d ask.

The moment I saw the pediatrician’s pitying smile, I said, “She’s eating! Can I show you?” Before she could answer, I pulled down my shirt and scooped my nipple into T’s mouth. T latched, and sucked a little, and then started crying again. The pediatrician’s pitying smile deepened in its regret.

“Yes. I’m sure you are doing everything right,” she said. She paused and then said gently, “Sophie, has anyone brought up the possibility of Insufficient Glandular Tissue Disorder with you?” I was horrified. Insufficient? Was this woman calling me insufficient? This must have shown on my face, because the pediatrician said, “Oh, I’m sorry. I know that that can sound sort of… mean. That’s the medical term for it. I’m not making a judgment.”

“No, no one's ever said that to me,” I snapped at her. She had seemed so nice! I thought. But she was one of those terrible back-room doctors in the pocket of Big Formula all along.

“It’s just, I’m looking at your breasts, and they fit the description of a person with IGT. Widely spaced, tubular shaped, bulbous nipples…” Well, yeah. My breasts were all of those things. And yeah, I’d never seen other breasts like mine. I had a momentary flashback to the time my entire freshman dorm did plaster casts of our breasts in support of breast cancer research. (Honestly, what didn’t we do in support of breast cancer research in 2008?) Mine just fell apart. It didn’t look like anyone else’s; everyone else had breasts that looked like breasts; my breasts were a heap of literal garbage. The pediatrician interrupted my reminiscence. “I’m sorry you’re just now finding out about this. I really am.” She took a long pause. “But we really need to figure out a way to feed your daughter. I hate to ask people to use formula who don’t want to, but –”

“— My roommate!” I interrupted. The word “formula” still sounded like “demon juice” to me.

“I’m sorry?”

“We live with this couple who has a baby and anyway she has all this breast milk she’s frozen and she offered it to me, and could we use that? Would that be OK?” The pediatrician’s face lit up.

“That’s amazing!” She said. “Wow. I’m not medically allowed to endorse you using unregulated breast milk, but off the record, as long as your roommate is healthy and isn’t using drugs, that could be a great alternative.” She looked even more relieved than I felt. “And here’s the number of an excellent lactation specialist in the area. Who knows? Maybe I’m wrong about the IGT.”

*

"The moment I saw the pediatrician’s pitying smile, I said, “She’s eating! Can I show you?” Before she could answer, I pulled down my shirt and scooped my nipple into T’s mouth. T latched, and sucked a little, and then started crying again. The pediatrician’s pitying smile deepened in its regret."

Many people I know have reported that breastfeeding was the hardest thing they have ever done. The New York Times reported that while 83 percent of babies in the United States start out on breast milk, only 56 percent are breastfed by 6 months, and only 25 percent drink breast milk exclusively.

The New York Times article cited above followed four breastfeeding mothers in day-in-the-life style reporting. Reading their schedules is like reading about a dystopian future where rest is nonexistent and everyone spends all their free time trying to find new time management strategies and life hacks. Pumping while driving; pumping while peeing; pumping while your shoulders and head are in a Zoom meeting. It’s unrealistic to expect to be able to keep a career while also breastfeeding a baby. Many of the mothers I know who breastfeed choose to take a year or two (or more) off work. That’s not something everyone is in a financial position to do, and as a result, I often hear those mothers talking about their privilege and resources apologetically, like, “I’m so lucky that this is my life.” And yet still: they aren’t getting enough sleep, they aren’t eating the food they want to eat, they so rarely do anything for themselves. Is this the best possible scenario?

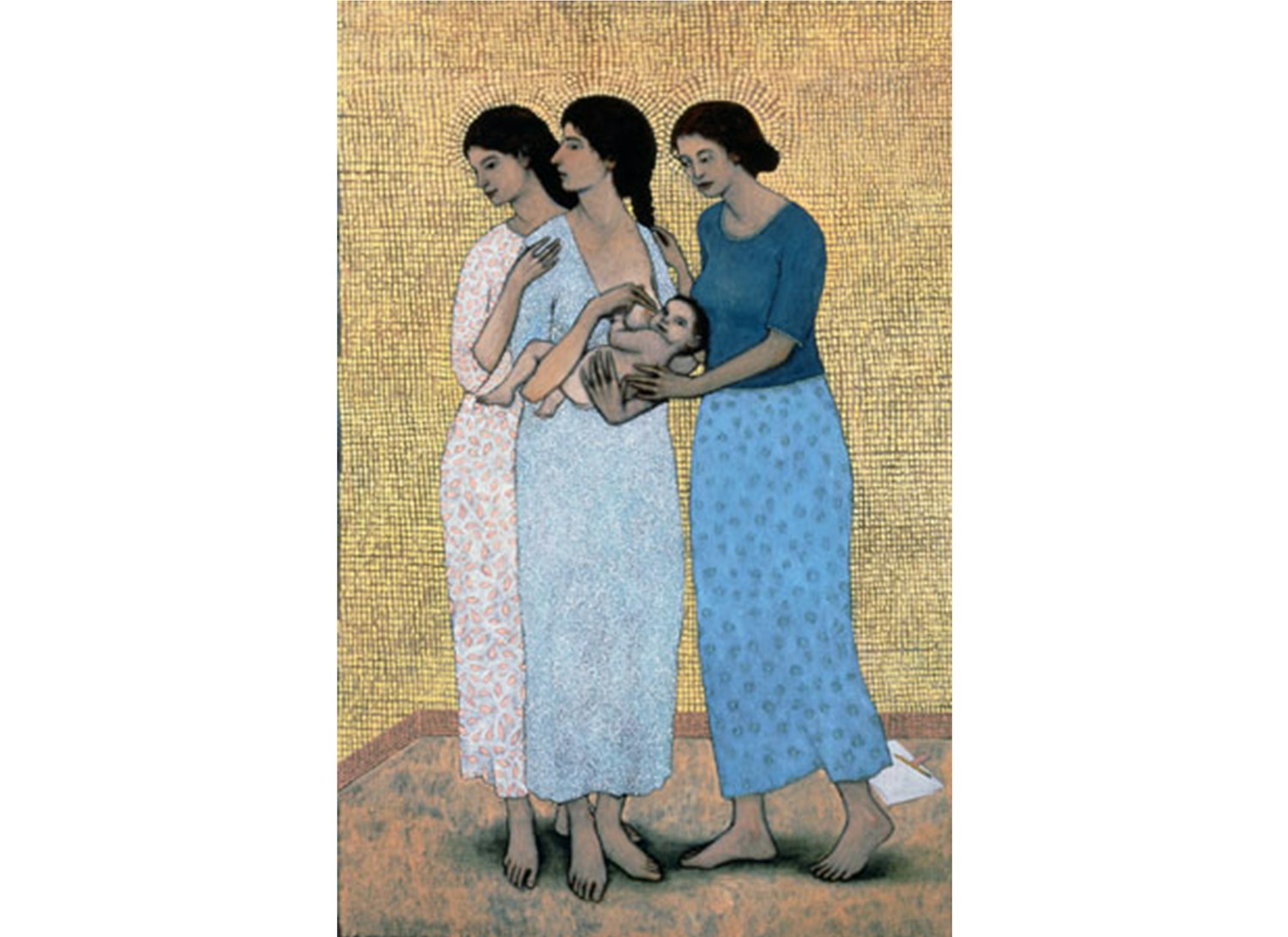

Cultural references to wet nurses date back to the Bible as well as Greek mythology. A wet nurse is a person who breastfeeds another person’s child, and while they have fallen out of favor since the invention of formula in the 20th century, there are still people who practice. In general, throughout history, wet nurses have underscored cultures of inequality. Enslaved people and servants were often hired to be wet nurses for the elite, sometimes against their will. In some cultures, the relationships between wet-nurses and the families they served were often special. In Vietnamese family structure, and in Islam culture, people who breastfeed other people’s babies are able to incur kinship rights.

These power dynamics are less problematic in instances where breastfeeding parents nurse each other’s babies in a reciprocal act. Although this is not as well documented, it’s been called cross-nursing or co-nursing, and there’s evidence of it dating back hundreds of years. But it’s not common today. In an article for The Guardian from 2007, Dr. Rhonda Shaw notes, “The exchange of body fluids between different women and children, and the exposure of intimate bodily parts make some people uncomfortable. The hidden subtext of these debates has to do with perceptions of moral decency.”

When I thawed the first batch of breastmilk from Bethany, I had no thoughts about moral decency or intimate body parts. All I could think was that I wanted my daughter to have enough food to eat, and that maybe this would make her stop screaming — and, in between those thoughts, that I loved Bethany on a level that somehow superseded even the word “family” because she was freely giving me a resource that was going to keep my baby alive.

I put the milk in a silicone bottle and gave it to Luke to feed T with. I took a picture of Luke feeding her because I knew I’d want to write about it someday, but as I try to write about it, I can see that it’s actually impossible to explain, like so many things about parenthood (and love, and growing up, and death, and all the other quintessentially human experiences), and there is an annoying paradox of language being insufficient for this thing that I so deeply wish I could explain to you. When I took the picture, I imagined I’d eventually have the words for this: what it was to fill an emptiness, what it meant for Luke to participate in caretaking that, until then, he’d had no control over, how it stopped a kind of bleeding, how it healed a kind of crack. But the image that comes to me isn’t really about Luke holding the bottle and T finally quieting; it’s an image of Bethany and her husband and their baby and our house, and how I felt held. Like, I was going to metaphorically drop this baby, because my boobs were failures, but no! There were all these arms there to catch me; Bethany’s voice to whisper, “Hey, I’ve got you. Relax a little.”

When it comes to breastfeeding, people have opinions. It’s hard to figure out how to unblur facts from fiction; there is some truth to the idea of the Evil Clutches of Big Formula. There is a lot of excess breast milk — people continue producing it after their own babies stop eating it, and they have to pump in order to avoid intense physical pain. Donating your breast milk is difficult, because breast milk has to be regulated. You can buy breast milk on a not-difficult-at-all-to-access black market, and it isn’t illegal, but it also isn’t medically recommended.

In 2022, when a national formula shortage prompted more parents to seek peer-to-peer breastmilk exchanges (which proliferated Facebook), the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Food and Drug Administration came out to discourage “casual sharing.” They cited the high risk of breast milk getting contaminated, or that babies might be exposed to scary medications or drugs that parents might not disclose taking or using. It is possible to donate milk through a formal “safe” channel, like an FDA-approved milk bank, which thoroughly screens all donors and pasteurized all donations. But it takes a lot of work to get approved to donate to a milk bank, and the milk that’s been donated is usually reserved for the highest risk infants (as it should be).

There’s really only been one major study, conducted in 2013, about unregulated shared breast milk. The study was only around breast milk that was purchased online and then shipped – not donated to be used freely and distributed locally. That breast milk had high levels of salmonella and other bacteria, and was sometimes diluted with cow’s milk, and it wasn’t always shipped properly. There isn’t any research about infants like mine who are given other people’s non-regulated breast milk. All the articles I could find about sharing breast milk included quotes from pediatricians and breastfeeding experts, but none from parents who had tried it. I wasn’t able to find stories from parents who regretted sharing breast milk, nor stories that signified the kind of danger that the AAP or FDA suggest might exist.

To be clear: I believe in science, and I can only share my own story, which I understand to be unique.

"When I thawed the first batch of breastmilk from Bethany, I had no thoughts about moral decency or intimate body parts. All I could think was that I wanted my daughter to have enough food to eat, and that maybe this would make her stop screaming"

I ended up using all of Bethany’s breast milk, and it kept my daughter alive and healthy for two full months before we ran out and had to switch to supplementing with formula. Even when I stopped what I was doing every three hours to pump, I never produced more than two ounces of milk a day. My nipples bled, my body ached, and I cried constantly because of my lack. The other lactation specialist we visited confirmed what the pediatrician supposed: I had IGT. I wasn’t ever going to make enough for T. She put her hand on my shoulder and said, “This is sad, and you can mourn. This is not how you wanted things to go.” I did mourn, but I also beat myself up, willing my breasts to be different and better. Eventually, T was not interested in my nipple at all – probably because it didn’t give her very much to be interested in. The last time I breast fed her, she had been rejecting my nipple for weeks, and she took it just one more time, and I knew that it wasn’t going to happen again, so I thanked her, and I cried, and I wished it was different.

I wished it was different, and also, I was so, so grateful. I didn’t get to choose my breasts, but I did get to choose my roommates. I did get to choose my family. And I imagine that browsing the internet trying to find a stranger willing to share milk with me would give me reason to pause, but taking breast milk as a gift from my best friend, whose favorite foods I knew, whose values I understood, whose hardships I’d witnessed, whose companionship had already nourished me, was easy. My parents were grateful, Luke’s parents were grateful, and my grandparents were grateful. No one said, “Ew, these weird communal poly hippies are sharing BREAST OOZINGS with each other!” Because it was so obvious that this was the best possible thing for the baby that we all collectively loved.

"I ended up using all of Bethany’s breast milk, and it kept my daughter alive and healthy for two full months before we ran out and had to switch to supplementing with formula. Even when I stopped what I was doing every three hours to pump, I never produced more than two ounces of milk a day. My nipples bled, my body ached, and I cried constantly because of my lack."

I saw a tweet the other day from an account called @PhDMumLife that said, “My hot take: for anyone considering having kids, the nuclear family concept is a hoax. Start a commune. Or live in a multigenerational, close-knit setting of another kind. It genuinely takes a village. Child-rearing in a nuclear unit is some version of hell.”

I know a lot of people who have made the nuclear model work for themselves, and who report to be very happy. But I know no parents who wouldn’t be grateful for a little help (or a lot of help) now and then, if only they knew how to get it without feeling selfish or rude or like they were overstepping. The best way to be able to ask for help is to get emotionally close enough to people that you trust them, and they trust you. One of the most beautiful things about the breastmilk arrangement was that Bethany wanted someone to use it. It’s not easy to make breastmilk! The hundreds of ounces she donated to our family represented hours of pain and physical labor that she desperately didn’t want to see go to waste. There was no way to express to her how grateful I felt, but I knew that she was, from her depths, glad to be able to show up for us, too.

Sophie Lucido Johnson is the author of the forthcoming book KIN: The Future of Family, which is about easeful and non-traditional ways to build community wherever you are. She is a cartoonist at The New Yorker, and writes the newsletter You Are Doing A Good Enough Job. She lives in Chicago, where she keeps bees.