Navigating neurodivergence

Words by Mari Werth

In 2007, I devoted my life to educating kids on the autism spectrum. In 2018, I had an autistic baby.

Liam was almost born in a waiting area, when our hospital had no open rooms. I birthed him after vomiting uncontrollably following an undiagnosed staph infection. It was an unpleasant pregnancy and birth, but he was a pleasant baby. He slept through that first night in the hospital; he rarely cried; he fit into the folds of our family.

It was our toddler, who was two at the time of his little brother’s birth, that we were worried about. He was deeply jealous of his little brother, throwing rabid tantrums, heaving things, waking multiple times at night. He would grow out of it, everyone said, and he did, right around the time of his third birthday.

So when Liam entered toddlerhood with extra energy, explosive tantrums, and bone-hard rigidity, we thought nothing of it. As he approached preschool age, he was slated to enter the same public elementary as his brother, and none of these behaviors had subsided. I remember the week before he entered school, I turned to my husband and said, He will melt in a classroom environment. My husband was nonplussed, but I knew better.

When I was 22, I became a founding teacher in the Nest program, an inclusion-model program in NYC public schools for kids with low support needs autism (Asperger’s, as it was called then). The program was incredibly progressive for its time; including, supporting, and neuroaffirming neurodivergent kids was my mantra as I grew in my career. The Nest program is now replicated in hundreds of classrooms and dozens of NYC public schools. I’m now 40, and I’ve never not worked in a Nest school.

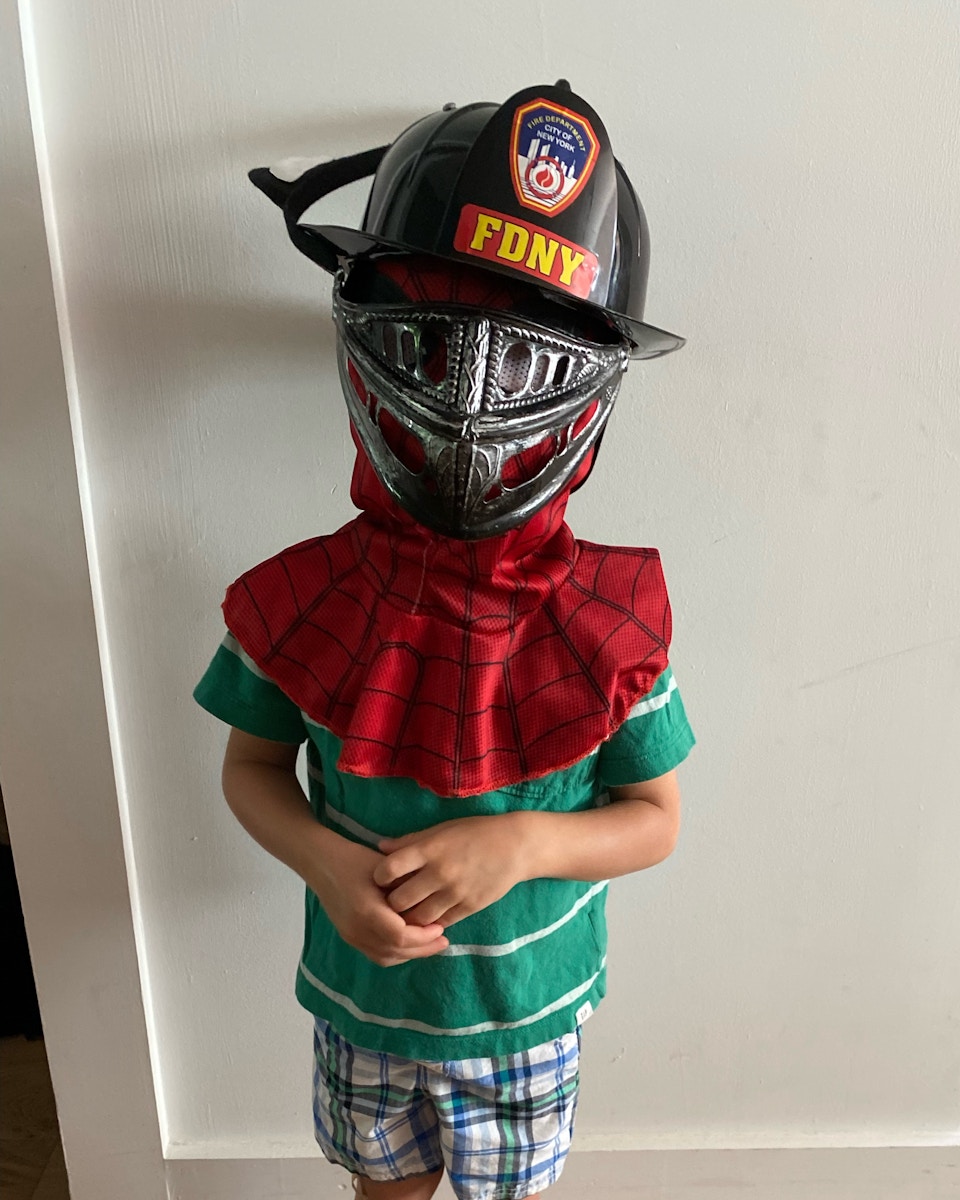

Liam’s first week of preschool was tough. He ran out after us, screaming and crying. I remember my son’s first week of school, my best friend told me. It was exactly the same. Only it wasn’t the same. Liam never stopped running out after us. One day, he even made it to the street. He began demanding to wear a police uniform to school, with the belt so tight it made marks on his stomach. His rigidity, his sensory needs, his anxiety were becoming more—not less—pronounced as the year wore on.

Towards the end of Liam’s Pre-K year, I received a call from the school social worker. She told me Liam ran out of class, was in her office, and was unable to calm down. I froze, then made a call to have Liam evaluated.

My husband was supportive, as he always is, but also skeptical. I don’t want him labeled. It’s not a label; it’s a diagnosis. You know too much and are pathologizing him. It isn’t typical for a Pre-K kid to continue to run out of the classroom.

My friend group’s reaction was similar. He’s so social. The spectrum isn’t linear. He makes eye contact and spoke early. These are outdated tropes of a much more nuanced disability. Aren’t we all a little autistic? No, but I bet a lot more people would fit the diagnostic criteria than you would think.

Liam was soon diagnosed with ADHD, then level 1 (low support needs) autism.

Since Liam’s diagnoses, and subsequent services, he is doing better in school, but his progress isn’t linear. I’ve had to fight for his school and community to understand that when he refuses to do work, he is not being willfully defiant. I’ve had to advocate for a basic understanding of his neurotype, the very same neurotype I’ve devoted my life to. I often find myself the only expert in the room with my child’s team, which is both empowering and crushing.

Picture listening to music, and it’s just missing the mark. My husband runs a record label. It’s trying so hard to work, but it can’t; the musicians aren’t trained. Now picture the music is sucking your kid’s spirit out of his body. We have to find a better school environment for him.

By the end of first grade, Liam's sense of self was so damaged that he frequently mentioned self harm.

" I’ve had to advocate for a basic understanding of his neurotype, the very same neurotype I’ve devoted my life to. I often find myself the only expert in the room with my child’s team, which is both empowering and crushing. "

"Liam’s disability is invisible. If you were to meet him, you may think he is a spunky, bubbly, energetic kid. You may think he lacks boundaries and says surprising things. You may think he needs better parenting. Who is raising this child? Where is his mother?"

Liam’s disability is invisible. If you were to meet him, you may think he is a spunky, bubbly, energetic kid. You may think he lacks boundaries and says surprising things. You may think he needs better parenting. Who is raising this child? Where is his mother?

Liam is autistic.

Writing those words is still hard, and feeling how hard they are is confusing to me. Autistic kids are my life’s work, my bread and butter, some of my favorite humans, my professional passion.

Liam is autistic.

It hits different when it’s your own kid.

I’m now fighting for Liam to be in the Nest program, the very program I helped to found. To note, there are hundreds of applicants for very limited seats. I helped to build this net for children with Liam’s profile, but now I’m not sure if it can properly hold him; getting into Nest is like winning the educational lottery.

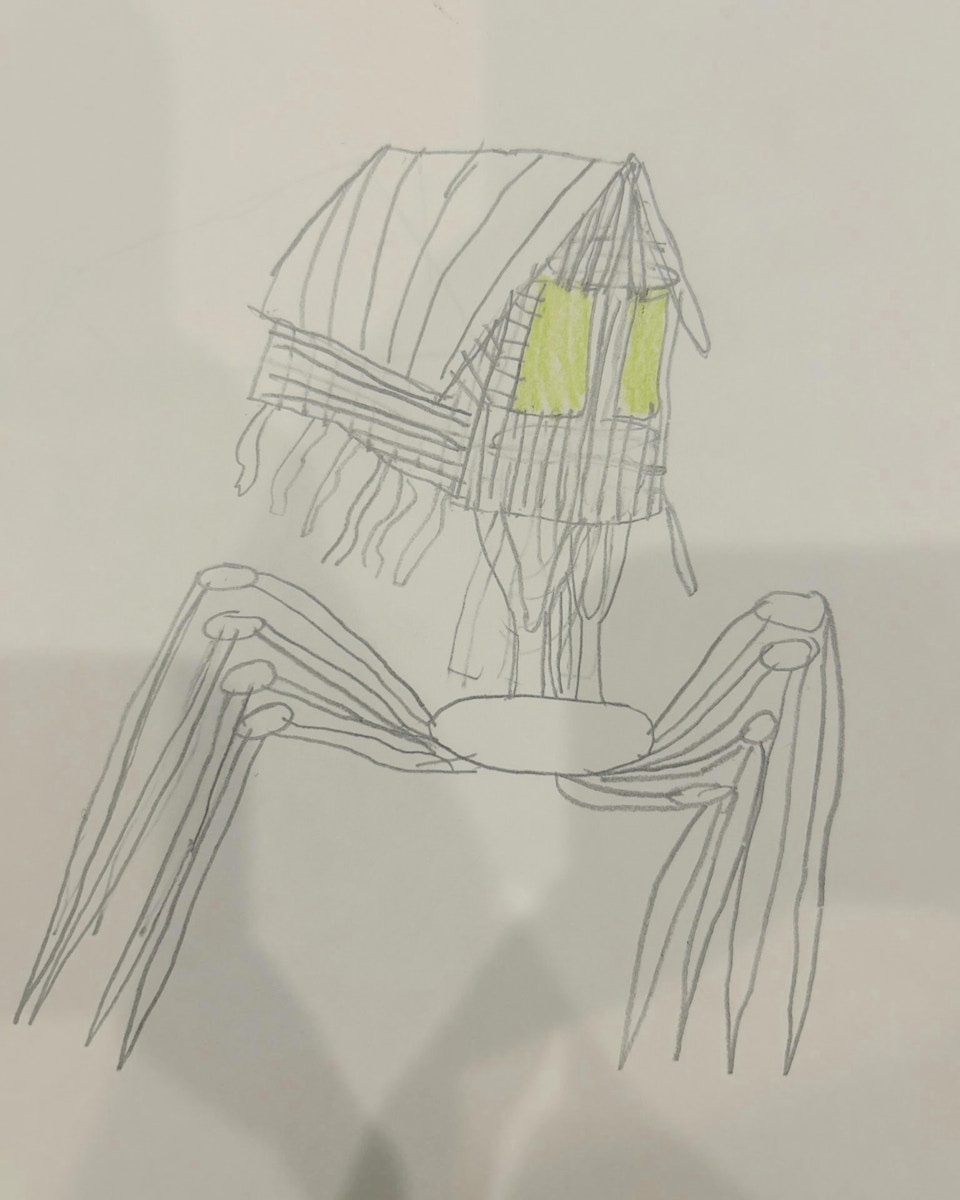

Liam’s brain gives him beautiful and unique strengths. He can focus for hours if he’s interested in a task. He draws with more detail, observation, and control than I do as an adult. Academics in school are a breeze. He is deeply creative, understanding a vision for what he wants to create immediately and forcefully. He makes friends easily. He has a contrarian and witty sense of humor. Liam has a giggle that will make even the most salty human laugh alongside him.

I want Liam to know his brain is not wired wrong. I want him to feel proud of his identity and strengths and needs. I want him to have community. I want to have community. Neurodivergence should not engender shame, because neurodivergence is natural.

Liam had something called a "home visit" today from his teachers; it's a tenet of the Nest program. He just got in. His teachers came to our house and played with him and told him how excited they were to have him in their class. They learned about his interests and silliness and deep creativity. They made him a book (called a "social story") about what their class will be like, and what the social expectations will be, and who will be there to support him and connect with him.

I cried big tears of relief after this visit. At dinner every night, we discuss three things that were notable in our days. Usually, when it's Liam’s turn, he deflects and talks about poop and big butts, a defense mechanism he’s learned to try to mask and fit in with the other little boys. During his turn tonight, he told us how his teachers came over, and how they were so nice.

Mari Werth began her career in 2007 as a founding middle school teacher in Nest, a special-purpose program that integrates students with autism into inclusion-model NYC public school classrooms. She is a proud assistant principal at PS 165, which serves a beautifully diverse community, including 30% of students with disabilities. She was the recipient of an Aspiring Leaders Fellowship at Summer Principals Academy at Teachers College, Columbia University.

Mari is mother to an 8 year old, and L, age 6. She is relieved and proud to know that L recently got into the Nest program, and she knows the program will help him to grow, reflect, and accept his kooky, quirky self just as he is.