Getting Sticky With Reshma Saujani

Photos by Randy Stulberg, Words by Anamaria Glavan

Childcare isn’t an isolated concern reserved for nuclear families; it’s an issue that impacts society en masse. That makes it a policy problem, one that must be addressed at scale. Accessible daycare and paid leave aren’t luxuries but rather signs of a functioning country that values its citizens. That’s the crux of Reshma Saujani’s work.

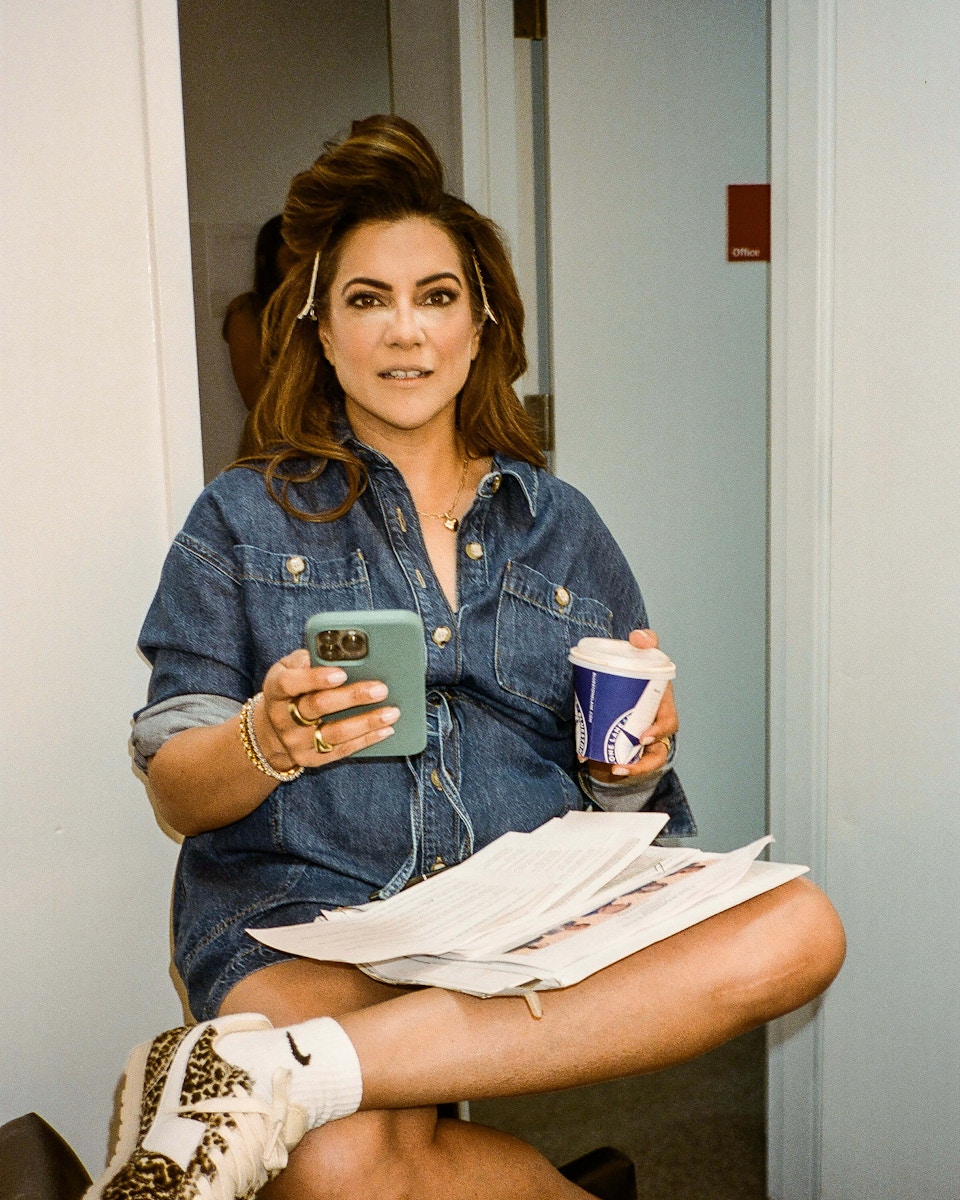

Reshma Saujani is the founder of Girls Who Code, a nonprofit organization dedicated to closing the gender gap in technology by teaching girls coding skills and inspiring them to pursue careers in STEM fields. She is also the founder and CEO of Moms First, an advocacy group focused on elevating the needs and voices of mothers in policy conversations, from paid family leave to affordable childcare and workplace equity.

Below, Reshma reflects on being the daughter of refugee parents who built meaningful lives through the lens of the American Dream — and how her current policy work is about reimagining that dream so that a once-common tale becomes possible again for a new generation of kind, smart, empathetic human beings. Ones who deserve a chance.

“There is no gender equality without child care”

Sai was born on January 25th. The world fell apart in March. I was on maternity leave but I had to go back to work to save Girls Who Code from being shut down. And I was seeing it from two vantage points. First, from the perspective of our students, half of whom live below the poverty line. Many of them were supposed to be on their way to college, but because their mothers were essential workers, they had to stay home and take care of their siblings.

We often talk about the generational cycle of poverty for girls—especially girls of color—when we think about Africa or India. But it was happening right here, in the Bronx and in Brooklyn. And it was happening because we don’t have childcare. We don’t have paid leave.

And then, from the inside—within my own team at Girls Who Code, and in my own life—I saw how little support we had, how much we were all hanging on by a thread. I realized how much I had been conned about women’s equality and why we’re still so far from it.

I had really bought into the lie that I was the problem. That it was my fault. I just needed to color-code my calendar. I needed to marry a different person. I needed more confidence. If I just did this or got that, I could balance it all.

And what the pandemic showed me was: Oh. I’m not broken. The country is broken. I’ve never been set up to succeed because we have a broken structure of care. That structure keeps mothers from equality. It keeps women from equality. There is no gender equality without child care. Period.

"We often talk about the generational cycle of poverty for girls—especially girls of color—when we think about Africa or India. But it was happening right here, in the Bronx and in Brooklyn. And it was happening because we don’t have childcare. We don’t have paid leave."

Recoding the American Dream

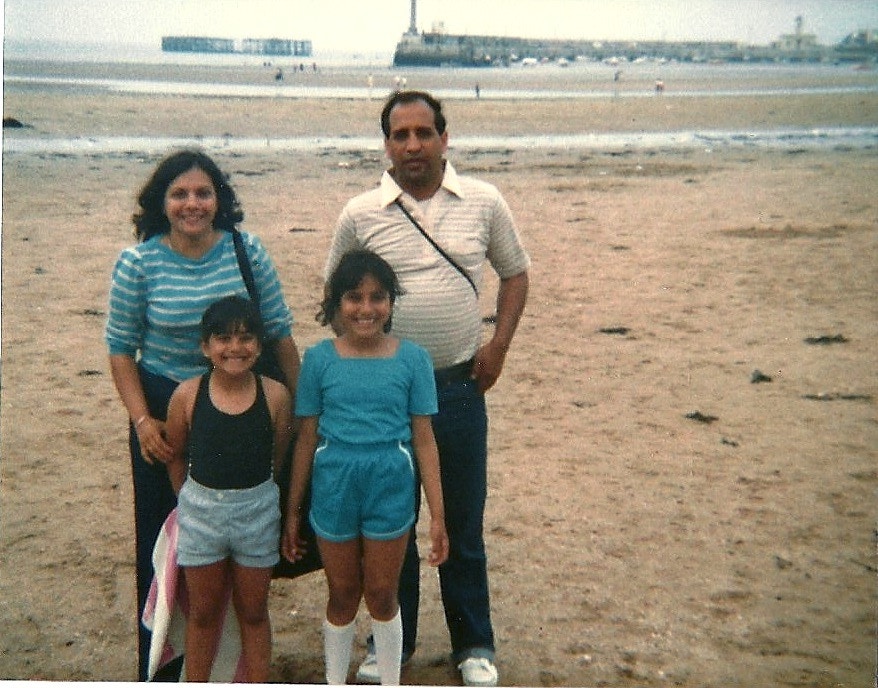

I love this country. My parents came here as refugees. My mother was in her early 20s, pregnant with my sister. They were two of a thousand refugees granted status to come here. The rest of their family was scattered in refugee camps around the world. When they arrived, they had no friends, didn’t speak the language. They were wearing shorts and t-shirts in the dead of winter.

The Catholic Church took them in. They fed them. Clothed them. Gave them shelter. And to me, that is what America looks like when it’s at its best: we take care of the poor, the vulnerable, the young, the sick, the old. My passion for public service, for fighting for people who don’t have someone fighting for them, comes from how my parents came to this country.

What I do every day is, as we say in Hinduism, my seva, my act of service. It’s my way of giving back to this country. That’s what patriotism means to me: wanting everyone to have a real shot at the American dream.

That means no one has to choose between feeding their kids and paying for daycare. That means everyone has a shot at the middle class. When my parents came here, they had $11 in their pockets. No jobs. Two daughters. And now, one’s a doctor, one’s a lawyer. We were able to jumpstart generations. Can people do that today? Do we make that possible anymore? That’s what I’m fighting for.

With Girls Who Code, I focused on girls. It wasn’t because I thought tech was cool. It was: how do I lift girls out of poverty? How do I make it so a girl leaving a homeless shelter and a girl leaving an apartment in Chelsea can start on the same baseline and have an equal chance at achieving the American dream? Now with Moms First, I’m focusing on mothers. My mission hasn’t changed, it’s just expanded.

"That is what America looks like when it’s at its best: we take care of the poor, the vulnerable, the young, the sick, the old. My passion for public service, for fighting for people who don’t have someone fighting for them, comes from how my parents came to this country."

Motherhood is not a personal problem

There are a ton of motherhood influencers. There are a ton of organizations that are organizing moms to fight for issues. But American motherhood is broken. And who’s working on fixing American motherhood, which is really childcare and paid leave?

When I started Girls Who Code, the reason why we were able to teach 600,000 girls to code and reach billions was because the private sector said, I have a talent problem. I can’t hire enough engineers.

The public sector was not addressing this problem. They weren’t teaching kids to code. So the private sector was looking for an intervention to help increase the number of people graduating with engineering and computer science degrees.

In many ways, it was a model I built at Girls Who Code that worked—and it was in partnership with the private sector. So when I looked at childcare, I thought, Why are we looking at this through the lens of it being a personal problem that families have to fix?

People can’t work without childcare. Why am I not hearing every single CEO talking about the fact that 50% of Americans live in childcare deserts? Or that 55% of parents are in debt because of the cost of childcare? It’s an economic issue.

So then it was like, ding, ding, ding, ding, ding. We need the same kind of intervention that we had at Girls Who Code. Business leaders. Private sector. Coming in and saying, Hey government, do something about this.

The second thing that became clear to me was that the way we were talking about it wasn’t working. We needed to figure out how to take an issue that was number 13 on the list and elevate it to number one.

Expanding the conversation

We were organizing around these issues from a progressive, female perspective. But it wasn’t an issue that was just affecting people on the left nor just affecting women. So how do we talk about it differently? How do we engage different people into the fight?

My son would sit with my Girls Who Code teacher, listening to my speeches. And he started asking me, Mama, why do you just talk about the girls? What about the boys? He was genuinely asking.

I started looking at the data. Around that time, we were starting to have more conversations about the fact that boys were lonelier, more anxious. They weren’t graduating college. Men and boys are struggling. You can’t deny it.

And then the election happened. And I saw part of the narrative being sold to men was: the reason you’re suffering is because we gave these women over here too many rights. We gave them too much power, too much opportunity. And if we take some of that away, you’ll do better.

That is a lie. It’s a con. And I didn’t want my son being sold that lie. I didn’t want him buying into it. Because that’s not how we help them. That’s not how we solve these problems.

That really motivated me—as a mother of sons—to say, No, no, no. Wait a minute. This isn’t the way. If we’re going to win these fights, we need to engage men. And the way we’ve been talking about men is wrong.

When we looked around, men were doing something. They were doing care work. They wanted to take their paid leave. But society gaslit them when they did it.

The language we use turns them off because it feels like we’re attacking them. I got dozens of handwritten notes from men after the summit. Every single one thanked me for giving them space and not blaming them.

"There are a ton of motherhood influencers. There are a ton of organizations that are organizing moms to fight for issues. But American motherhood is broken. And who’s working on fixing American motherhood, which is really childcare and paid leave?"

Bartering the girlboss for the tradwide

We have to reject the binary. That’s the first thing. We have moments in history where the pendulum swings. And we’re in a moment of traditionalism. The thing being sold now is almost a trade for the girlboss era.

We either talk about childcare from the perspective of, We need it because women need to work, or, We don’t need to invest in this because women should stay at home. And what we should be pushing for is the truth, and where mothers actually sit, which is: Give me choice and freedom. Give me the choice to make my own decision about whether I want to work, stay home, or do a little bit of both. Don’t sell me one thing or the other. That’s what Moms First is about. That’s what we’ve been building.

The presence problem

I told myself I would try one more IVF cycle. I called my doctor and she said “No. You can’t keep doing this. This is going to kill you. If we do one more cycle, you’re not going to try and carry. We do it for surrogacy.” I did that cycle when I was 43 and that’s how Sai, my second child, was born.

After his birth, I started working to change the surrogacy laws in New York. At the time, surrogacy was still illegal in the state. I had never seriously considered surrogacy before that. In fact, I had been adamantly against it.

Shaan’s best friend has two dads who’d used surrogacy, but for me, it felt like the ultimate failure. I’m someone who works hard. Why is my body conspiring against me? I blamed myself. I thought, If I just do more acupuncture. If I cut out gluten. If I stop working so hard, maybe then I can make my body do it.

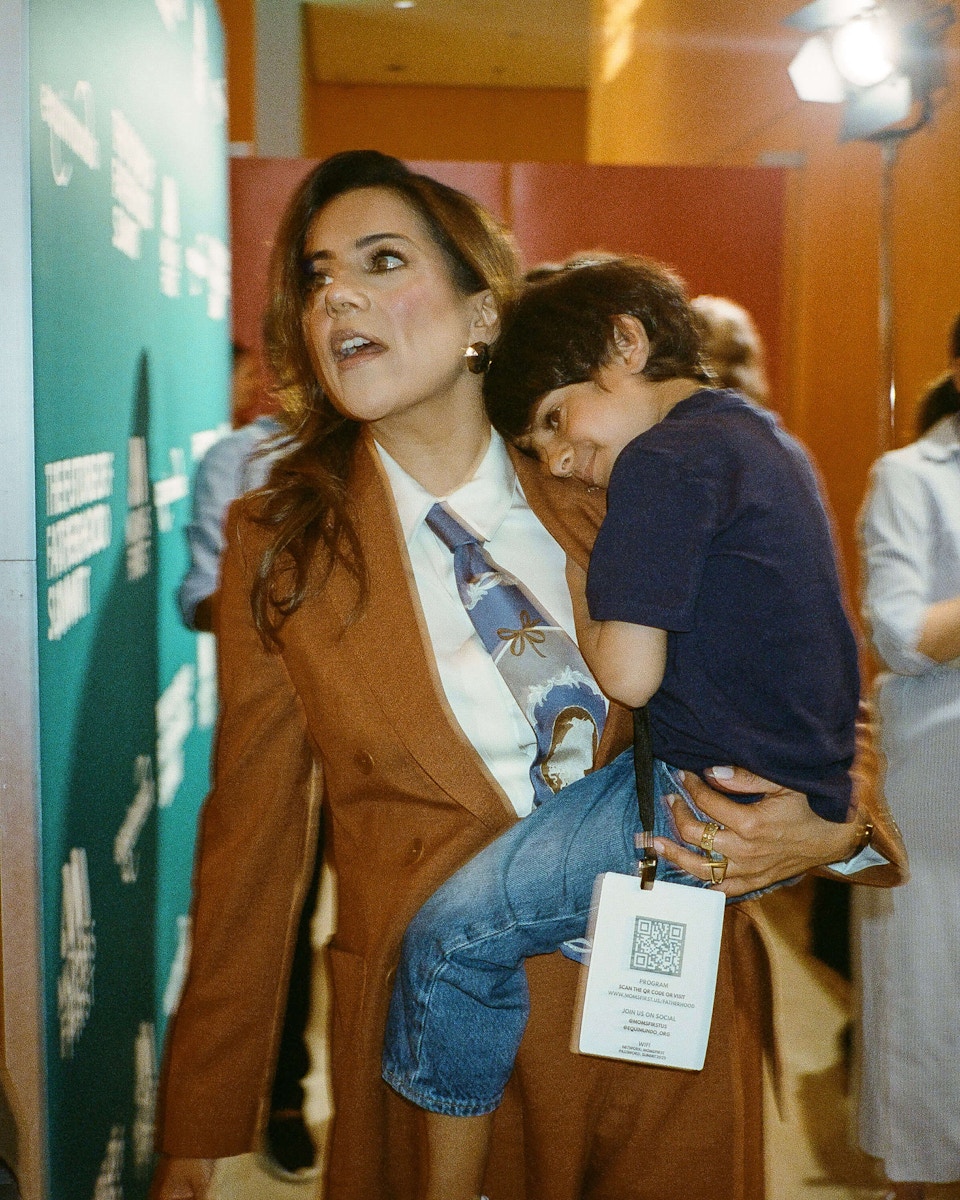

And when I had Shaan, I thought, Oh, I’m gonna show you. It felt like the ultimate girlboss moment. I’m gonna show you I can breastfeed while talking to governors and giving a speech with no help. I wanted to prove I didn’t have to sacrifice my career to be a mom; that I could still be a great mom.

And you know how it is when you’re trying to work and be with your kids; you’re never really doing either fully. When I had Sai, the pandemic in that sense was a gift. It made me stop traveling, it made me slow down, it made me be present. The idea that you could die at any moment made me realize: Oh wait, I don’t have to do it this way.

Culture eats policy for breakfast

The version of motherhood I appreciate now is the freedom to have choice. The freedom to move in and out. I don’t feel like I’m sacrificing my job for my kids or my kids for my job. If I could create the perfect workplace structure, that would be it.

This idea of facetime—of being always on, always available, always working—is stupid. It doesn’t lead to productivity. When you give people control over their time, and clear goals, they can decide for themselves how to manage it. They’re not sacrificing family for work. And they’re still crushing it.

It’s about women being respected and valued in their homes, in their workplaces, in their doctor’s office. Because I really do believe culture eats policy for breakfast, all day, all night.

One of my favorite lessons came from my friend, Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson. It’s this idea of blooming where you’re planted. How do I make the most out of the moment I’m in right now? Not regretting the past, not obsessing about the future, but being fully present.

Actually, the next generation is bursting with empathy

I always say: the girls in my Girls Who Code programs are just incredible. This next generation is so empathetic. They care less about material things. They're laser-focused on the world around them and on solving the problems we’ve left behind. And I feel good about that.

You can see it. They’re outraged by war, by poverty, by climate injustice, and they’re doing something about it. They’re smart as hell.

So I have a tremendous amount of hope in the next generation. That said, I think one of the challenges I’ve given myself is this: no movement succeeds without the voice of young people.

But when it comes to child care and paid leave, it’s hard to get folks who aren’t parents or don’t want to be parents to see the urgency. That’s something I’ve been thinking a lot about.

We have a lot of young women who work with us who may not want children, but they care deeply about care. Maybe they’re caring for a parent. So part of my work is figuring out how to get the next generation engaged in motherhood, even if they don’t want to become mothers themselves.

"This next generation is so empathetic. They care less about material things. They're laser-focused on the world around them and on solving the problems we’ve left behind. They’re outraged by war, by poverty, by climate injustice, and they’re doing something about it. They’re smart as hell."

The gift of aging, of evolving

There’s something I really love about midlife that I’m leaning into right now: To go up, you have to go in. There’s something about this phase of life that comes with big change. (It’s what motivated me to launch My So-Called Midlife with Lemonada; this idea that women are forced into irrelevance once they reach a certain age, when in reality we are just getting started.)

You lose a parent. You lose your job. You lose your soul dog. You have these huge, cataclysmic moments of grief, pain, and suffering, and they force you to reexamine your life. They force you to look at the places where you’re stuck.

I lost my race at 30. I was this working-class kid trying to make it in the big city. And I had (still have) real issues with rejection. I was a brown girl in a white working-class neighborhood that didn’t have many friends.

That theme of rejection has haunted me for a long time. And I didn’t even realize it until about a year ago. Now when it shows up, I can name it. I can see it. Midlife has given me the opportunity to sit with my own demons and to evolve. It’s helping me become a better person. A better human. And that’s such a gift.