Getting Sticky With Rena Karefa-Johnson

Words by Emily Barasch, Photos by Kanya Iwana

Freedom—what does it mean to get free and to stay free? Who gets to be free and stay free? These are questions that lawyer and activist Rena Karefa-Johnson has devoted her life’s work to. As Vice President for National Initiatives at FWD.us, an organization that fights for criminal justice and immigration reform, she is at the forefront of the prison abolitionism movement, working to release incarcerated individuals and intrinsically rethink how our society ruthlessly dons out punishment. Her first job out of Harvard Law (what, like it’s hard?) was a juvenile public defender. She also worked on the historic bail reform 2020 bill in New York state and Black Mama’s Day Bail Out.

(For context: 80 percent of women jailed in this country are mothers with children under 18 and an estimated 58,000 people every year are pregnant when they enter local jails or prisons. Moreover, the U.S. has more than 20 percent of the world's prison population, even though it only makes up about five percent of the world's total population and research has consistently shown incarceration is an ineffective way to achieve public safety.)

Karefa-Johnson’s first child, Kenrick, was born in 2019, and the experience of having him during that year of pandemic, isolation, and racial reckoning still reverberates. With her now-two kids at home, she navigates issues around punishment and repair, post-baby body feels, and interracial marriage. While her political values are perhaps considered radical (though they shouldn’t be), her stance is never rigid. It is instead steeped in empathy, humanity, humor.

Below, Karefa-Johnson on the scope of her work and how it’s evolved, both as a mirror of broader societal shifts and in tandem with her own motherhood journey.

A continuation of legacy

My husband wasn’t sure about having kids given the state of the world. I understood what he meant, but it didn't resonate with me. I come from people who had children while literally in bondage. And as a Jewish person, so does he. It doesn't feel like a determinative thing given that times are looking weird or tough to not choose life. For me, it was a big thing to choose to perpetuate my lineage. I feel so deeply connected to my grandparents and my ancestors and honored to be in their legacy, but I also feel a huge responsibility to carry that on through my own children. I said to my husband, you're getting neurotic, I get it, but it's going to be fine.

But fast forward to now, I have a five year old and an eleven month old. We're in the middle of the collapse of the American Empire and the rise of fascism and climate disaster. I am sometimes thinking, in this context, why did I have children?

I lost my father when I was four and it was a big part of my life. I'm acutely aware of what it means to lose someone important to you, and I'm acutely aware that having more people that are important to you increases the probability that you have to go through that trauma. So I always knew having children was going to be a whole new level of battling fear, anxiety, mortality and precarity.

It's definitely been that way for me. I have been more anxious as a mom than I would want to be, especially around their health and their well-being. At the same time, it’s brought so much joy and meaning into my life. I named my son after my father. I did it because it felt right to me, but I didn't realize how spiritually powerful it would be to have everyone in my family saying my dad's name all the time. Saying his name has brought his presence back in a way that's been so cool and powerful.

I’m not surprised by the heaviness of motherhood. I am surprised by this inkling, or maybe it’s a theory I've had: that I’m doing this generational work to honor my ancestors. And how much I actually feel the fruits of that every day with my kids.

"It doesn't feel like a determinative thing given that times are looking weird or tough to not choose life."

Can you handle this?

I don't love straight men as a concept. So I kind of knew once I was in a serious relationship with one, especially a straight white man, there would be absolutely no way I could commit unless l could pressure test his ability to understand and deal with patriarchy, white supremacy, and white fragility. I myself was in therapy, but I started couples therapy to answer, Can you handle this?

I knew that to build a life together, we were going to have a lot of differences. I need to make sure that we're on the same page about big things. I need to know that we're able to talk, hear, and respect each other in a way that doesn't make me feel like I'm reproducing the hierarchies and the kind of micro and macro-aggressions that I experienced as a Black woman in the world in my home. I'm not going to have to fight for my life for him to get to see my perspective, the way I did in our law school classroom, or the way I do in meetings in my bedroom. I'm just not doing that.

A big part of couples therapy is making sure we have a practice of how to talk about things that are quite honestly centered around me. Not that he doesn't get to be heard or seen, but we have norms around when it's important for him to listen, be curious and affirm versus when it's important for him to push back.

The nuclear family model = absolutely insane

I always described my first year of motherhood as a mixture of boot camp and bliss, heavy on the boot camp. It was insane. Hi, it's my first day of a new job that I'm doing from my tiny little Zoom office. Please don't acknowledge my child taking three of the shortest naps he has ever taken in his life and then deciding that he was going to scream at decibels I had never heard.

There was nowhere I could go. There was nowhere I could hide. My husband was also working full time, so we were both trying to juggle; I literally would have my son playing with toys, underneath my desk, trying to pretend he wasn't under there.

When Kenrick was two weeks old, he got a UTI and was admitted to the NIQU. I had a lot of health anxiety already, which I think a lot of new moms do. Having that in COVID was wild because my kid would make a noise that even sounded like a cough and I would have a full, full body panic attack meltdown. I was like, here it goes, we're having it! It was hard also for me to calibrate how much of that was a normal adjustment to motherhood, and how much of it was this COVID weird hellscape parenting that we were in.

"I always described my first year of motherhood as a mixture of boot camp and bliss, heavy on the boot camp"

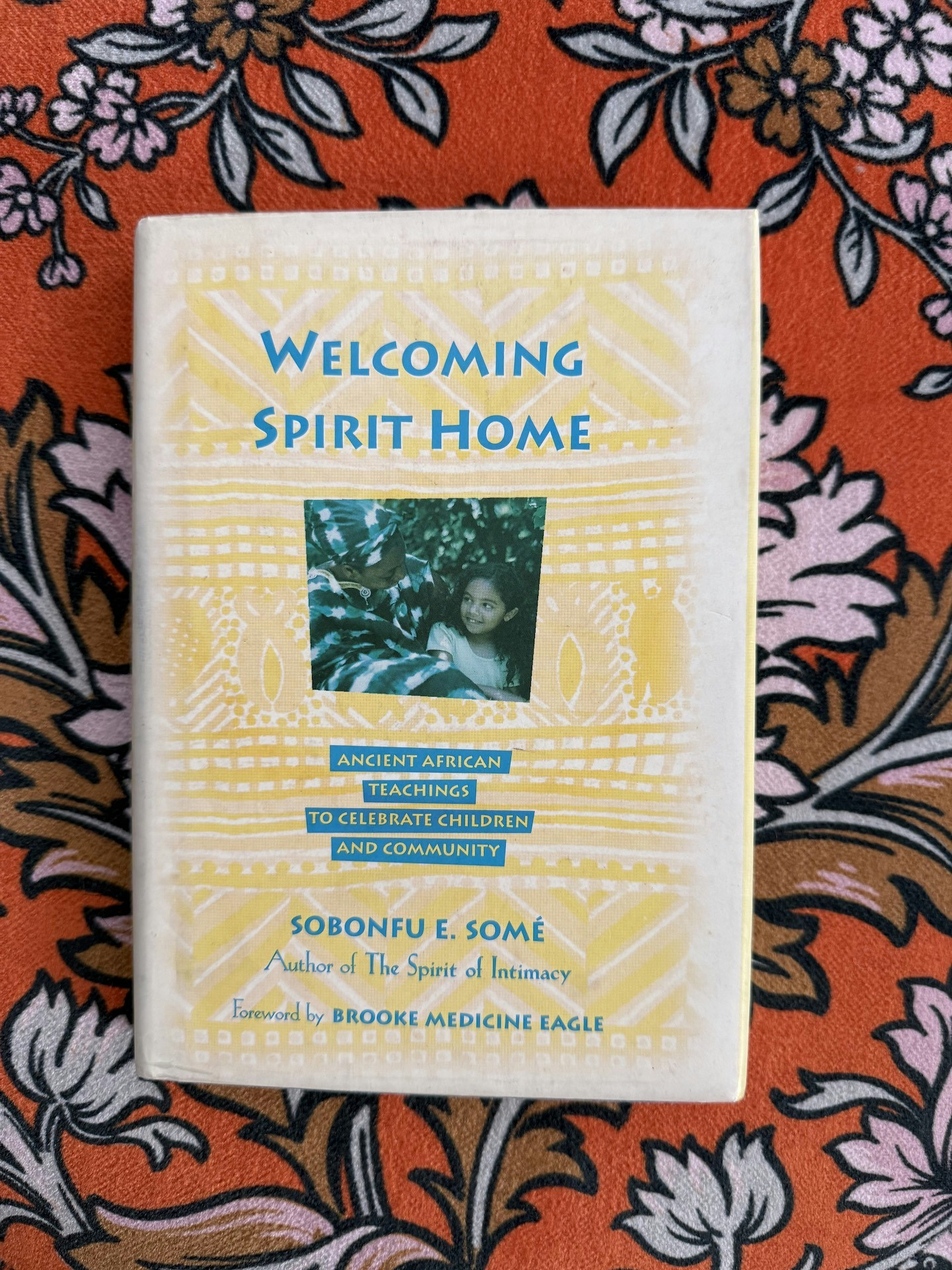

The way we raise children in America, the nuclear family model, is insane and doesn't make sense. COVID forced me to realize what a broken model that system was because it was just the three of us in the house all the time. And it felt like, I need my sisters and my friends here both for camaraderie for me, but also to help raise my child. I need our dinners to look broader than the three of us. I cannot mother outside of a community.

But at the same time, the tiny crystal of positivity was that I had this incredible experience that came with a very high cost of my sanity, which was being home with my kid for the first two years of his life. I was working more than I wanted to, but he was in earshot of me that whole time, and that felt special and rare, especially given that he was my first.

When you take one life, an entire family goes with it

I do human rights work. My calling is to get people out of prison and jail, and in this country, it's predominantly Black people who are in prison and jail, and predominantly Black people who are harmed and killed by our mass policing system. We all remember the summer of 2020 as a moment when many more people became politicized around our police state and the ways it enacts hugely unchecked violence on communities—especially Black communities. It was beautiful to see so many more people sign up to come along on a journey that had been trodden by far fewer before. But also, it was really painful.

My work forces me to grapple with how easy it is for folks to take a life, whether that's locking someone in a cage for their whole life or killing them like in the case of Mike Brown and George Floyd and so many others.

Human beings are valuable. When you're a parent, I think you see how much is poured into a child. There's a level of immorality of killing someone alone, but then there's also the additional level of how you’ve robbed all of the physical and emotional and spiritual resources that people put into this kid. Our children are so precious to us. How many nights do mothers or parents or caretakers not sleep? How many days are we stressed out and losing time because we're worried about a sniffle that they have? How many things do we sacrifice for ourselves so that we can give to our kids? How many days do we not take care of our own needs so that we can take them to do something that they want to do? I was envisioning this tsunami of love, care, and resources that go into every child on behalf of their community, just snuffed out like it was nothing.

I felt very tender that summer as a new mom. My son was turning one, and I was struck by how precious and invaluable he was: not because of anything he did, but simply because he was alive. I was also realizing how our children become repositories for everything. We pour our love, hopes, and dreams into them—not in a projecting way, but with a willingness to give all we can, in the hope that they grow up whole, happy, alive, and vibrant. That was true for Breonna Taylor’s, Tamir Rice’s, and Kalief Browder’s mothers, too.

"Human beings are valuable. When you're a parent, I think you see how much is poured into a child. There's a level of immorality of killing someone alone, but then there's also the additional level of how you’ve robbed all of the physical and emotional and spiritual resources that people put into this kid."

Abolitionism informs motherhood

Having a kid makes you realize that everybody is, at their core, good. So much of what goes wrong in our society is based on what people encounter and what needs they don't have met. That’s what creates a tartar around that core, and that can lead to really fucked up behaviors.

I look at my kids now and I realize that I'm going to do my best to raise them with values that hopefully help them be kind and caring. In my family we say, we want to afflict the comfortable and comfort the afflicted, and I hope that they grow up guided by that. I also understand that if they were to have experiences beyond my control—ones that harden them, or if violence were done to them in ways that made them want to inflict violence on others—their behavior would never be okay, but it would never erase their worth. I think most mothers feel that way. It’s just interesting how easily people can hold that kind of compassion for their own loved ones but struggle to extend it to anyone else.

I identify as an abolitionist, which is not a very common position. To me it is the belief that we can't and shouldn't fix our problems by caging people. Yes, we have real issues of violence and harm, all types of horrible things, but the way that we look to cage and invisiblize people does nothing to actually solve those problems. In a lot of ways, it actually aggravates those problems.

Mothering has been interesting to my overall politics and the work that I try to do in the world. I have a lot more empathy for why people want to punish. I have been in the position where my kid just seems to not be listening to me, he’s wilding out, and I very much think: I get why people want to punish kids.

Or I’ll yell, and I’ll recognize: that didn’t make anything better… but it was also important for me to do in that moment. I shouldn’t have done it, but it was serving some kind of purpose for me. And I think what a lot of young millennial parents are struggling with right now is this question: What does it mean to know that yelling at or punishing your kid is, A: sometimes really hard to avoid, and B: does serve a purpose for us in the moment, without telling ourselves a false story about what it’s actually doing.

It’s not actually doing anything. If anything, if it’s changing your kid’s behavior, it’s doing so out of fear, and I don’t think any of us feel comfortable with the idea that we want to practice fear-based parenting. So, I try to hold these two things at once: I don’t necessarily always have the answer, and I also know I’m imperfect and will make mistakes. But that doesn’t mean I have to justify what I’m doing by creating some theory about why it’s good. Sometimes, it’s just not good and not great. I’m human. I’m trying my best.

I mean, I wish people had that same orientation around our criminal justice system. Look, if you don't actually feel comfortable with certain people walking around, and you’re more comfortable with the idea of millions of people getting arrested and going to jail and prison? Okay, that's fine, but you don't have to pretend that's actually the best or the right way to solve our problems because it's not.

"In my family we say, we want to afflict the comfortable and comfort the afflicted."

It’s good to admit when it’s a “me” problem

It's all about the repair. What has been very interesting for me as a parent is recognizing that a lot of times when I snap at my kid, it is not a “him” thing, it is a me thing. Maybe he's doing a behavior that is objectively annoying or diabolical, but it also might be developmentally appropriate for him. And depending on what I am bringing to that moment, I can either handle it or I can't. So I've started trying to be honest. If I snap at him, I go back and I apologize. I usually snuggle with him for five minutes before he goes to sleep and that’s where both let our guards down. We have tender talk moments where I'll go back to the moments of the day that were hard and try to talk to him about it. I've taught him that mommy can be overstimulated and just dysregulated sometimes, too.

That second baby

My second child is lovely and amazing. The thing about being a parent is that becoming one radically transforms your life, and after your first, you’re already doing it. And having a second child means you’re doing it more. The transition from zero to one was harder than the transition from one to two, because I'm already like: Well, guess what I'm not going to do on the weekends: relax or do fun things for myself or dates with my husband.

My baby is almost 11 months old and I still feel like it can be traumatic or chaotic to leave the house with both of them: the coordinating of naps, the snacks, the breast milk, the whatever, can be extremely overwhelming.

With the second, I do feel more body stuff. With the first, I was very much like: This is a beautiful thing and breastfeeding is beautiful, and I don't care that my body looks or feels different or isn't mine. This time, I felt more angst. I'm still breastfeeding and I want to be breastfeeding. But I also want to smoke weed. I'm going to a Beyonce concert and I might want to do some drugs but I can't because of breastfeeding.

An art form that encompasses many mediums

When I first had Kenrick, I was like: What the fuck is this? I would call my mom crying, so stressed. And she would literally dead-faced say: No, baby, I'm so sorry. I can't even imagine how you're handling all that. She was a working single mom of five kids. My father died when my twin sisters were seven months old. I was four, my sister was seven, my brother was ten. She did the unthinkable. If I were her, I'd be like: Girl, if you don't shut up!

My mom made me realize that mothering is a craft. Mothering is an art, and some of us have to work harder than others to master our art. And it's a bunch of different mediums. There's no one way to mother. There's a million ways to mother incredibly, but I see my mom and I'm just like: You're not new to this, you're true to this. She makes it look effortless in the way that I know people don't like because it's invisibilizing labor, and I think that that's true.

But you know, who doesn't make it look effortless? Me. I am groaning, moaning, complaining on Twitter, and complaining to my friends. I love my kids so much, but I find it hard. You can see that I find it hard. Mom obviously had real challenges, but she is a master at mothering. It's been incredible to watch my kids benefit from that.

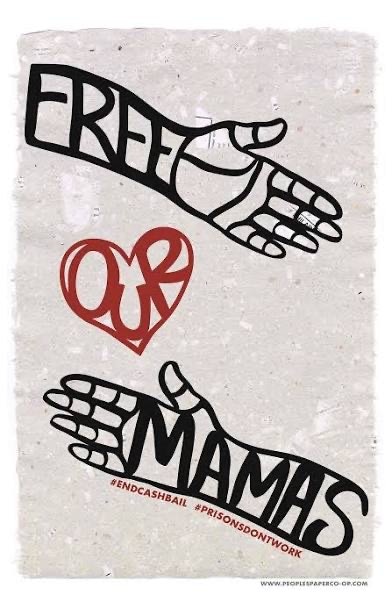

Incarceration is a mother’s issue

Incarceration is a woman's issue. It is a mother's issue. Somewhere near 80% of the women in jail in prison are mothers. These are people who are just like us, who have babies and struggle to breastfeed, and are up late at night googling what their kids' poops should be looking like. But they’re trying to do all that while in a literal cage. We are now as a society unable to see or raise up these people because we've decided to invest in punishment over repair, restoration and investments.

"Incarceration is a woman's issue. It is a mother's issue. Somewhere near 80% of the women in jail in prison are mothers."

Mass incarceration is a woman's issue, a mothers issue, because of how many women and mothers there are in jail and prison and because of the uniquely awful treatment they receive. Until about ten years ago, pregnant women in California could be shackled while giving birth. Pregnant women in prison and jail often have to pay for general hygiene products like tampons and pads. If they can't afford that based on the slave wages they make in prison, they have to figure out how to go without them.

When I was a juvenile justice attorney on Rikers Island in the boys unit with sixteen and seventeen-year-old boys, the people I spent the most time speaking to weren’t my clients. It was their moms. It was their mom was calling me. Their mom was trying to follow up about things. Their mom was collecting support letters or any type of thing that we could use in court or at the arraignment to make sure their kids got less time. It was the mom who was putting second mortgages on their home so that they could make the $5,000 bail so that their child could be out. These issues have been siloed and coated in ways that make it easy for even well-meaning people to be like “I care about this in a benevolent way, but this isn't really my issue.” But any mass incarceration is an environmental justice issue. It’s a public health issue. It's a reproductive justice issue. It’s a mother’s issue.

--