Getting Sticky With Laura Chautin & Masami Hosono

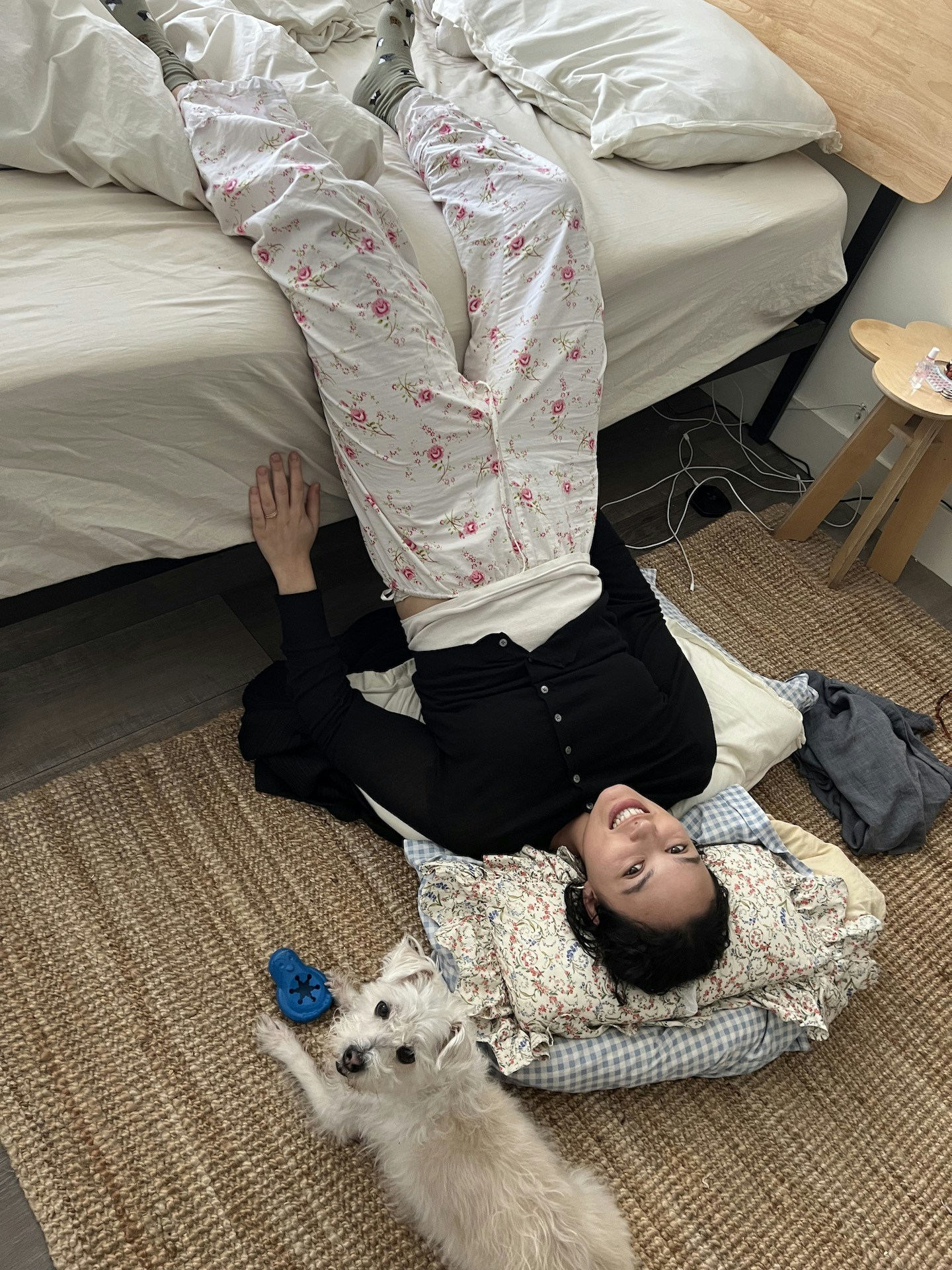

Laura Chautin and Masami Hosono live in Vinegar Hill with their daughter, Kokoro. Laura is an artist whose delicate, dreamlike work feels suspended between memory and imagination. Masami is a hairstylist, DJ, chef, and the owner of Vacancy Project, an East Village salon built on the radical idea that everyone deserves to feel safe and seen.

Right now, they’re in it: navigating postpartum, new parenthood, and the mountain of costly paperwork that comes with being a queer family in a country that still makes it harder than it should be. And yet, the U.S. is far from the most difficult place to parent as a queer couple. Same-sex marriage isn’t legal in Japan — and when Laura and Masami visit Masami’s mother in Tokyo, they can’t actually “enter” the country together. This also complicates the process of getting Kokoro Japanese citizenship (though more on that later).

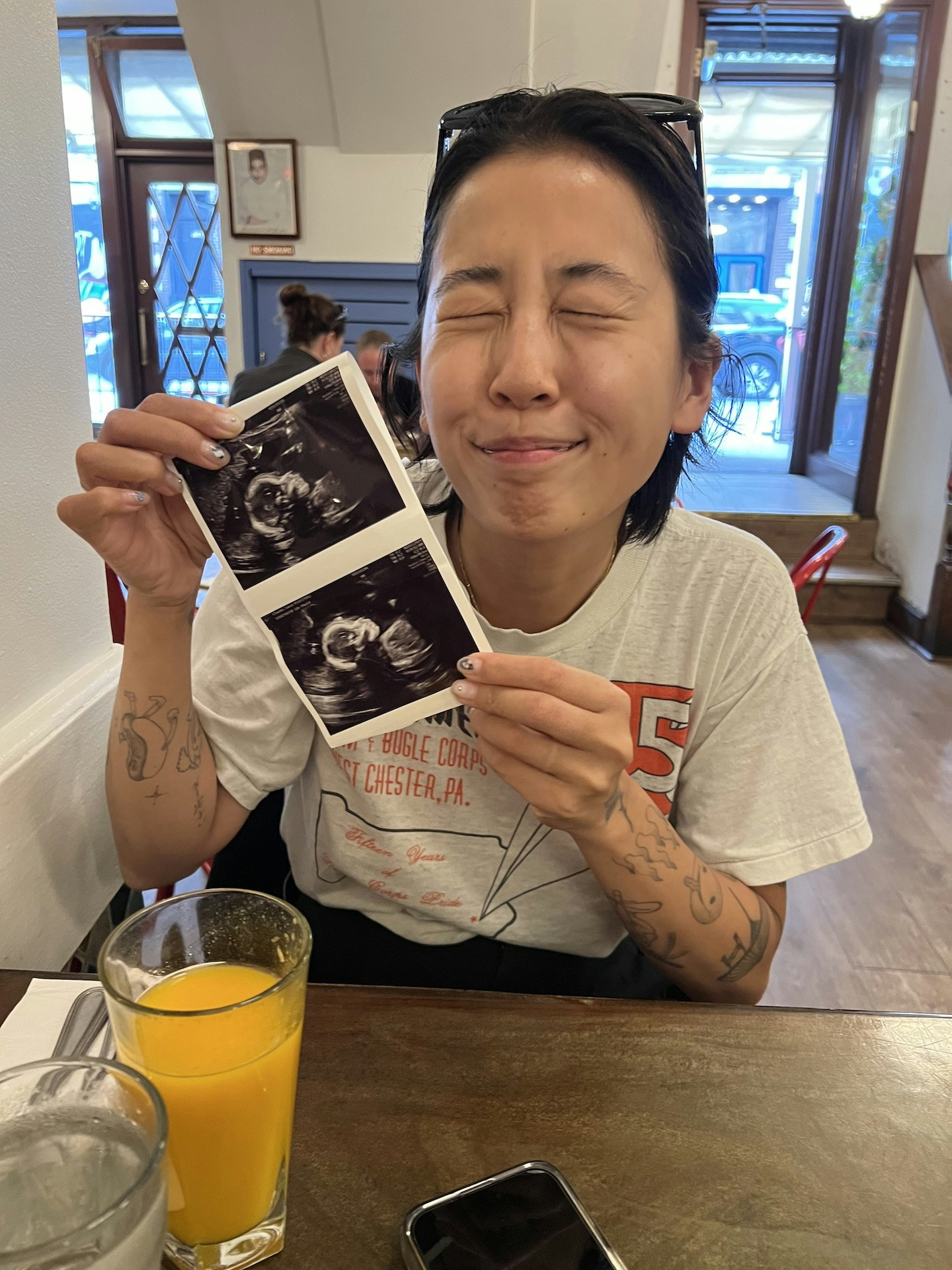

Below, the two share what it’s really been like: fertility clinics, finding a Japanese sperm donor, second-parent adoption, and the real cost of IUI. But more than anything, this is a story about what it means to be a parent. As Laura puts it: “I want people to see us not as queer parents, but simply as parents.”

“For us, this was the only way to conceive”

Laura: The fertility clinic we went to, Generation Next Fertility, felt pretty inclusive and didn’t make us feel bad. But we were going all the time—every month, sometimes multiple days in a row—and we barely saw other queer couples. It was mostly straight couples or women coming in alone. That dynamic felt very different from ours because for us, this was the only way to conceive. I’m 33 so I didn’t get labeled as a “geriatric pregnancy” but that term is so strange and harsh.

Postpartum on the other hand was a little weird. We gave birth at Columbia and some of the nurses weren’t super friendly. Who knows why, but I do wonder if it had to do with us being a queer couple. We’ve also run into issues with Vital Records since then. Our daughter’s birth certificate was wrong and there are so many gendered assumptions every time we call. They’ll say, Okay, so your husband— and I have to tell them I don't have one.

Yes, you see baby pictures of the donor

Laura: We originally wanted to use a friend as a donor but eventually decided to use a donor bank. At first, we didn’t have any information, but luckily we had friends who had used donors so we got to hear about all kinds of experiences, which helped us figure out what felt right. It was mostly through friends that we learned everything.

We wanted to use a friend, but then that friend started asking questions and wanted to be more involved than I was comfortable with. We also had other friends we considered, but they lived in Australia and that would’ve been difficult. Eventually I had to get over the hurdle of using an anonymous donor. Once I did, I realized that’s actually what I wanted. Our top priority was finding a full Japanese donor, if possible. Japanese donors are harder to find compared to Chinese American or Korean American donors. There were only seven total.

A lot of people ask and are surprised to know this: yes, you see baby pictures of the sperm donor, but if you want to see adult photos, you have to pay for them. That part was kind of disappointing. It feels like a scam in some ways. They know people are desperate and will pay…and we did, for a lot of it. You pay extra for everything. They give you the basics, like a general medical history and one or two baby photos, and then you can add on things like extended medical info, a voice note, or adult pictures. Some people don’t want to see the adult photo—we didn’t want to—and I’m glad we didn’t. At the time it felt like it mattered so much. But now that Kokoro’s here, none of that really matters.

"A lot of people ask and are surprised to know this: yes, you see baby pictures of the sperm donor, but if you want to see adult photos, you have to pay for them. That part was kind of disappointing. It feels like a scam in some ways. They know people are desperate and will pay…and we did, for a lot of it."

Birth class, meet real life

Laura: We ended up seeing my OB mostly because she took my insurance. It was fine for a while, but toward the end of the second trimester and into the third, I started to really not like her. I was getting more stressed and she said things like, Why aren’t you chill anymore? She also wasn’t nice about my weight. She told me I was gaining too much which really triggered me. And the way she talked, especially when explaining something difficult or medical, she’d just assume I didn’t understand. I was getting so stressed that my blood pressure would be high at the start of the appointments, visibly elevated, and then it would go back to normal by the end. It was insane.

And at one appointment, my OB said that because I had high blood pressure and Kokoro was measuring in the 10th percentile, I needed to be screened for preeclampsia and that if I had any other symptoms, I’d need to go to the hospital. And at 37 weeks, I had the mildest headache, no high blood pressure. But I had to go.

We’d taken a birth class and they told us, If you go to the hospital, they’re going to want to hurry things along and you’re probably leaving with a baby. So in the back of my head, I knew we might have her early but it was okay because 37 weeks is full term. When we got to the hospital, they took my blood pressure and got two high readings because I was nervous. I did get eight normal ones but based on those two high readings, they decided to induce me that day.

Sleep deprivation and shitty hospital food

Laura: Masami burst into tears. It was really sweet. Everything happened really fast and went fine, but the one thing I hated was the induction. I didn’t know anything about it even though we’d taken birthing classes. I got induced with the balloon and I nearly passed out because it was the craziest pain I’ve ever felt in my life.

The day nurse was amazing—she really made us feel good. We’d never held a newborn before; we don’t have babies in our families. And then suddenly we’re supposed to know how to breastfeed or swaddle, and swaddling is the craziest thing when you have no brain cells left and you’re like, Am I breaking this baby? And then the night nurse made us feel like complete shit. She was just mean. We had her for two nights and that was devastating because they’re super obsessed with breastfeeding. We wanted to breastfeed, but my nipple was bleeding and painful, and we hadn’t slept, and the hospital food was shit, but still, they were like, You have to breastfeed. It wasn’t until the last day that the lactation consultant came in, and that helped a little, but honestly, they should’ve come the first day.

Actually, fed is best

Laura: We've always done a combo of breastfeeding and formula, which is totally fine. But my experience at the hospital made me feel bad about it. I felt guilty when we got home and I started using formula. I was even sad that I was sad, which sounds ridiculous. Kokoro wasn’t latching but she loved the bottle. Masami was amazing through all of it, but I’d even get frustrated with them for telling me that I shouldn’t breastfeed while my nipples were bleeding. I’d think: No, I have to. Even though it was hurting me.

A lot of people I know are very much in the “breast is best” camp. Even friends, without realizing it, have kind of pushed that belief on me. It’s been hard. I was formula-fed and I turned out fine. The pressure is real, though. Interestingly, my friends in London have a much more relaxed attitude. They’re like, Do whatever you want. My baby’s formula-fed. We’re definitely not getting that same messaging from doctors here in the U.S.

Folding laundry is postpartum support

Laura: In the beginning, it helped when people brought us food, or even just folded laundry for us. Uber Eats and DoorDash were lifesavers because coordinating mealtimes was so hard. We don’t have a car so friends who could drive us were essential. They took us to the hospital, to the doctor; that was especially helpful during the first five days when Kokoro had jaundice. Friends with cars have basically been our lifeline. Our neighborhood, Vinegar Hill, has been amazing too. Everyone has a kid. One of the biggest gifts has been the number of hand-me-downs we’ve received—cribs, bassinets, so many clothes—all from other queer parents. It’s really made us feel like we’re part of a community.

Just posting about Kokoro on Instagram opened up a whole other support system. Moms I hadn’t talked to in ages, or even people I didn’t know that well, reached out offering advice, support, or just to chat. It’s been amazing. We haven’t hired a night nurse yet, but we’re thinking about getting a nanny—not just for help but also because I want Kokoro to speak Japanese. We’re hoping to interview a Japanese nanny sometime soon. And I want to go back to work, too.

The cost of IUI

Laura: I think people would benefit from a breakdown of the actual costs involved in trying to conceive, whether it’s through IUI or IVF. There’s so much variance. Can you go through a hospital with insurance, or do you need to go private? Sperm alone cost us $2,500 per vial. And when you factor in shipping, storage, and the IUI procedure itself, it was another $2,500—so $5,000 per try. We did four IUI tries, and none of it was covered by insurance. We planned to be on Medicaid during pregnancy so labor and medication would be covered for both me and Kokoro. That kind of planning made a big difference financially, and it’s something we definitely want to share with others.

"Sperm alone cost us $2,500 per vial. And when you factor in shipping, storage, and the IUI procedure itself, it was another $2,500—so $5,000 per try. We did four IUI tries, and none of it was covered by insurance. We planned to be on Medicaid during pregnancy so labor and medication would be covered for both me and Kokoro."

A group chat worth leaving off mute

Laura: For people in New York who think parenting isn’t possible here, or who just don’t know where to begin, it’s definitely hard, especially in today’s climate. But there are communities out there. I actually found one online that’s full of queer parents and seeing how many people are navigating this makes me feel so much less alone.

Masami: We're actually thinking about starting something like a queer parents picnic club, something small and casual. We’re really lucky. I’m a hairstylist so I meet people every day, but I know a lot of people don’t have any queer parent friends. Single moms too. There is the Brooklyn Queer Parents group but that’s just an email thread. So maybe something more personal, in real life, could be really nice

Same-sex marriage isn’t legal in Japan

Masami: A lot of tourists say that Tokyo is super family-friendly but as a local, it’s different. You can’t really bring a stroller on public transportation. People look at you like, Why are you bringing that? And there’s definitely a colder attitude toward things like babies crying or breastfeeding in public. Moms get judged a lot more.

Since I’m from Japan, where same-sex marriage isn’t legal, queer couples can’t even legally share parental rights. After becoming a parent, I realized New York isn’t perfect for queer parents either, but it feels so much better here compared to Japan. For example, Kokoro can’t have a Japanese passport because it has to go through the birth mother or something like that.

Laura: The biological father has to be Japanese, not a sperm donor—but if I were to give up parental rights, then Masami could be recognized. Maybe one day that will change. A lot of people don’t realize that same-sex marriage still isn’t legal in Japan. So when we go back, we even have to enter through different lines at immigration. I basically can’t travel to Japan alone with Kokoro. Maybe there’s a way for me to write a legal letter, but it’s still incredibly complicated, and if there’s an emergency while we’re there, we couldn’t even go to the hospital together. It’s pretty dangerous to travel or live there under those conditions.

"One important thing about being queer is that Masami has to adopt Kokoro. We have to go through a second-parent adoption process even though we’re married. In New York, our marriage is recognized, but especially with the political climate now, it’s essential for Masami to legally adopt Kokoro because they wouldn’t be recognized as a parent in some states."

Also, one important thing about being queer is that Masami has to adopt Kokoro. We have to go through a second-parent adoption process even though we’re married. In New York, our marriage is recognized, but especially with the political climate now, it’s essential for Masami to legally adopt Kokoro because they wouldn’t be recognized as a parent in some states. For example, if Kokoro needed medical care in a place like Texas or Kansas City and Masami wasn’t legally her parent, it could be a huge issue. And the adoption process costs a lot; it involves hiring a lawyer, undergoing a full background check, submitting taxes, having a social worker come to our house to ensure we’re not abusive, and then going to court where a judge has to officially grant the adoption.

I wish there were more accessible information on this; we only just started learning all of it recently. It’s crazy. We also spoke to a friend who used a surrogate, and even though one of the women was genetically related to the baby, both had to legally adopt the child. Being queer, being immigrants—this is supposed to be a good place to live, but now it’s starting to feel scarier. We were literally talking this morning about whether we should move to England.

We’re all just parents

Laura: I want people to see us not as queer parents—but simply as parents. It doesn’t have to be “two moms” or “two dads” or “one parent” or whatever. I want that recognition—like, we’re just parents, sometimes. I mean, people think it’s cool that we’re queer parents, and that is cool—but sometimes it also makes me feel like we’re all seen as one kind of thing. I want to be treated like everyone else. In New York, I definitely feel more of that equality… but even then, I still sometimes wonder, are we actually being seen that way? Are we treated the same as other families? And I do think someone has to be a role model to help normalize this—to show that this is just everyday life. We need role models, too.