Getting Sticky With Diarrha N’Diaye

Photos by Lelanie Foster, Words by AnaMaria Glavan

Diarrha N’Diaye was a salon baby. When she wasn’t in after-school programs, she was perched in a chair at her mother’s salon in Harlem, surrounded by women who’d known her since birth. That early exposure to beauty—and the entrepreneurial spirit of her Senegalese parents—would inspire her path toward democratizing the industry. (This despite a blip in the medical field, which she abandoned after failing stats, much to the disappointment of her parents. More on that later.)

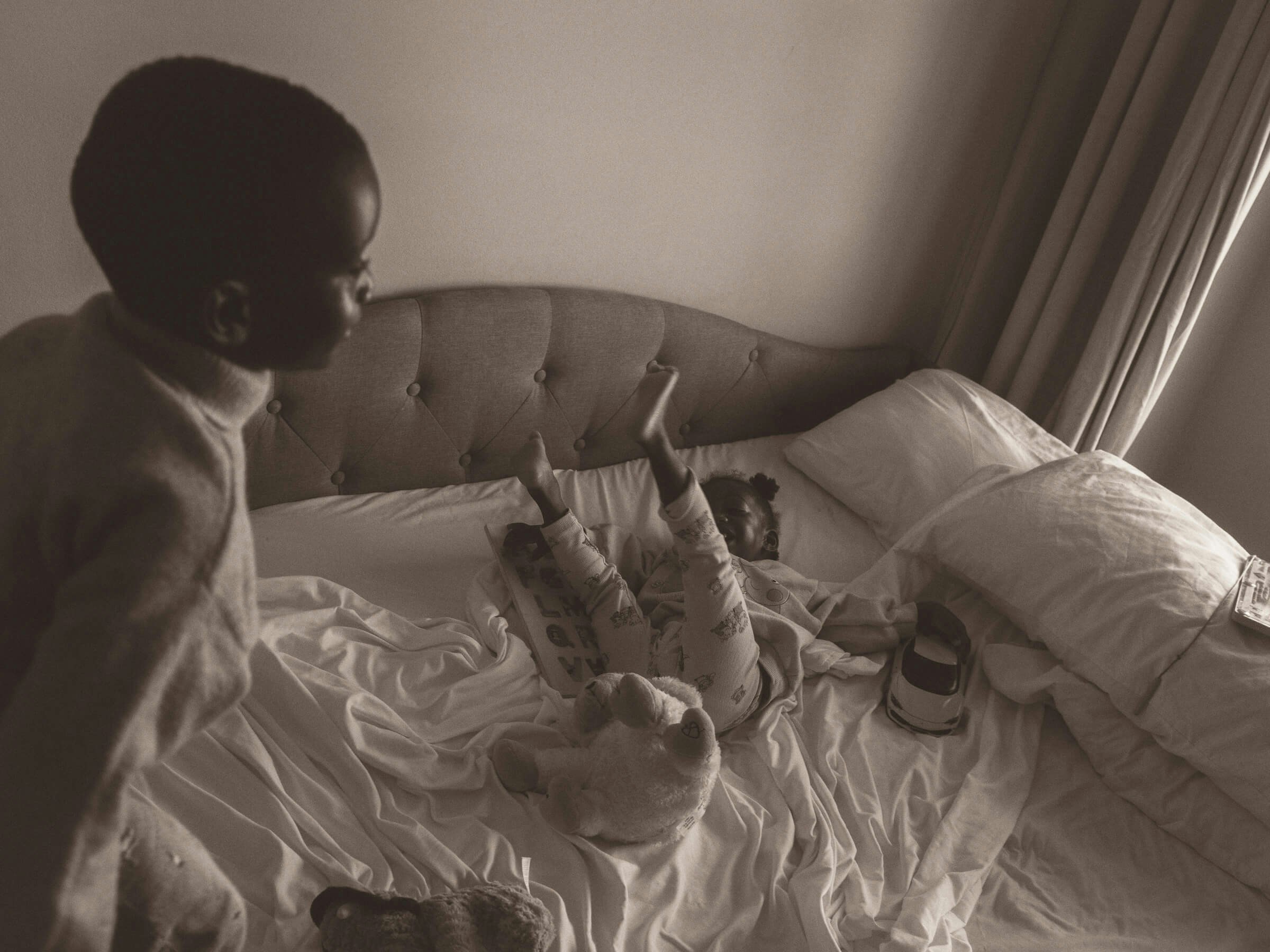

In May 2021, Diarrha announced her beauty brand, Ami Colé. She found out she was pregnant with her first son just ten days later. What followed was a beautiful whirlwind of chaos and learning in equal measure, as she juggled two births at once: one of a brand, and one of a child.

Then, July 2025: Diarrha announced the closure of Ami Colé. It was a shock. The brand was beloved, and seemingly doing well. Her accompanying essay for The Cut went viral for its raw honesty about the realities of entrepreneurship and the impossible pace of growth demanded of founders, particularly of ones who were under-resourced from the jump. In the months since, she's stepped into a new role: Executive Vice President of Beauty and Fragrance at Skims Beauty.

Below, Diarrha reflects on her past professional accomplishments—from Sephora retail to L’Oréal, Glossier product development, and the birth of her semi-firstborn, Ami Colé—through the lens of her Senegalese roots, the complex pride of being first-gen, and a dual inheritance: “My parents gave me the incredible gifts of grit and tenacity, but there’s so much I have to unlearn, too.”

“Why are you freaking out?”

My family is from Senegal, West Africa. Senegal is known for teranga, which means everyone opens their doors to you. Food is a big part of the culture and so is family: They really take care of moms postpartum, but that concept was mythical to me because I was born and raised in New York City.

My parents immigrated to Harlem in the late ’80s, and I saw grit and hustle but I never saw rest. My mother owned a hair salon and had me on her back as soon as she could walk; she would breastfeed me between clients. They watched me grow up.

I was part of the wave of kids who’d come from after-school programs and sat waiting for our moms to finish work. I had aunties at the hair salon, but that was the extent of the community I knew. We didn’t have any extended family here and I still never saw my mom sweat.

So when I was pregnant with my first child literally weeks after announcing the launch of Ami Colé—I announced on May 17th and found out I was pregnant on May 27th—my first thought was: My mom did it. I’ll be fine. Boy, oh boy…

As soon as I gave birth, I looked at my own mother through a different lens. She was suddenly always worried, and I would think, Wait, you made it seem so easy, why are you freaking out?

"As soon as I gave birth, I looked at my own mother through a different lens. She was suddenly always worried, and I would think, Wait, you made it seem so easy, why are you freaking out?"

Naming ceremonies and unanticipated retirements

My mom had forgotten how crazy motherhood was. She was desensitized; she’d seen women in the salon give birth and come back to work two or three months later like nothing happened. I don’t think she was prepared for how much help I’d need. My husband was the one cooking porridges, making soups, and really taking care of me.

Culturally, we have our baby showers a week after the baby’s born. That means getting dressed, glammed, stitched up, stretched out, and all dressed up in a girdle for this huge celebration. There’s a lot of superstition—they want to make sure the baby’s here and healthy—and the baby has no name for an entire week. There’s a naming ceremony exactly seven days after birth, usually a big one for the firstborn. It was February, freezing cold, my body was in complete shock, and there I was going to a tailor to get fitted.

(It was terrible. I would never recommend it. My body was engorged, cold, and shaking. I did not do that for my second child. In fact, I did postpartum very differently: I hired a nanny, got someone to cook for me, and asked for help. I learned it was impossible to do it all alone.)

And then, when my son turned three months old, my mom and dad decided to retire and move back to Senegal. It made me so sad and overwhelmed. Your whole life you hear: Don’t get pregnant, do it the right way, get married, have kids, and then you’ll have all this support. Suddenly, that support was gone.

And I get it. They’d been here almost 40 years. It was time for them to move on. But where does that leave first-generation immigrant kids like me, who have to figure it all out from scratch? They look at you and say, You’re so lucky, you live here, you have access, but actually, you have to figure out childcare, paperwork, medication, all on your own.

"When my son turned three months old, my mom and dad decided to retire and move back to Senegal. It made me so sad and overwhelmed. Your whole life you hear: Don’t get pregnant, do it the right way, get married, have kids, and then you’ll have all this support. Suddenly, that support was gone."

If it’s not the pregnancy, it’s the birth, and vice versa

My pregnancy was smooth with my son, then I was getting a pedicure and felt some pressure. I thought my water broke and my mom insisted I go to the hospital right away. They admitted me on a Friday—they were worried about an infection—and I didn’t give birth until Monday. No food, hooked up to everything, being poked, prodded, turned over, contractions… I was exhausted. And my mom, this strong lady, was freaking out in the delivery room so badly the doctor had to escort her out.

By Monday afternoon, they said we may need to do a C-section. My mom’s freaking out once again. She stayed at the hospital but went downstairs crying and doing all the things. I get rolled into the OR, my husband gets scrubbed in, and I’m basically in a T position waiting for this thing to happen. Suddenly my doctor looks at me and asks if we can try just one more time. I push, she uses the vacuum, and my son comes out. He’s silent for what feels like forever. That minute and a half felt like an eternity!

My experience with my daughter was totally different. The morning sickness was hard but the birth was smooth, and having skin-to-skin contact felt like a euphoria I’d never felt before. I had postpartum preeclampsia after the first baby and that felt sterile and scary. But with the second one, I felt like I was on a high. I wasn’t trying to figure out if my blood pressure was okay, or if his blood pressure was okay. She was so lovely, and we ended up naming her after my mother. It was such a beautiful experience.

Murphy's Law is a sick SOB

Out of nowhere, I’m drinking tea and talking to my husband, getting to know our first son, and I realize I can’t feel the left side of my face. The tea is scorching hot: One side of my tongue is burning and the other side feels nothing. I thought it was stress, so I went to sleep and woke up with my entire face drooped.

I thought I was having a stroke. I rushed to the ER—the baby was only three or four weeks old—and found out it was Bell’s Palsy. It was the most inopportune time ever. I was stressed out, freaked out, and on top of it all, running a business. My team was still new, the stakes were high, the company was doing well, and I was trying to hold it together. My body was in shock.

I did everything to try and save my nerves: all the steroids, I’m patching up my eye, doing my best. It was heartbreaking because as my son was growing, I couldn’t do facial expressions. I couldn’t talk to him or babble with him without drooling or struggling to eat. It was traumatic. Obviously, I was grateful it wasn’t life or death, but it definitely gave me PTSD about postpartum.

"I thought I was having a stroke. I rushed to the ER—the baby was only three or four weeks old—and found out it was Bell’s Palsy. It was the most inopportune time ever. I was stressed out, freaked out, and on top of it all, running a business. My team was still new, the stakes were high, the company was doing well, and I was trying to hold it together. My body was in shock."

We need to rebrand self care as selfless care, actually

I’m currently in the thick of it with an almost two-year-old and an almost four-year-old. I’m trying my best to take care of myself because I’m just not a nice mom when I’m exhausted.

My fuse was short, and I found myself spending more time in the bathroom trying to run away and regulate my nervous system. Now, when I take time for myself—when I go to a coffee shop, or get a massage—it’s not about being rah-rah, it’s just that your cup has to be as full as possible to pour into them. These are such formative years for my kids and they can feel everything.

In the beginning, you think you have to create a home, but no: You are the home. Home means a regulated nervous system, making your children feel safe and not burdensome. The more anxious I get, the more rowdy they get. But when I’m silly with them? They giggle and eventually wander off to play on their own. It’s so interesting to see that their being calm is dependent on my own regulation.

"In the beginning, you think you have to create a home, but no: You are the home. Home means a regulated nervous system, making your children feel safe and not burdensome. The more anxious I get, the more rowdy they get. But when I’m silly with them? They giggle and eventually wander off to play on their own. It’s so interesting to see that their being calm is dependent on my own regulation."

Noticing the success barometer, even as a child

My dad was a travel agent, and I remember sitting in his office on 34th Street spinning the globe, wondering what life looked like in places that were not New York City. Because my parents were so busy during summer, they’d send me to stay with family in Germany. I’d fly alone as an unaccompanied minor, as young as nine, to Frankfurt. That opened my eyes early to how big the world was.

There I was—a dark-skinned Senegalese girl in Germany—where everything was different and felt harsh: our complexion, our language, our food. But I learned I could adapt and connect through storytelling and fashion. My aunt had a magnolia tree in front of her house, and I’d think, What if I made the leaves into shoes? I’d take shoeboxes, size her feet, find leaves that matched, and spend all day making shoes out of magnolia leaves. And then I’d sell it to her: It’s so smooth, it’s one of a kind, I spent six hours on this, you owe me five euros.

That creativity sort of got capped at home. I felt the pressure to be successful because my parents had sacrificed so much in their entrepreneurial struggles in ’80s and ’90s Harlem. It was rough.

"My aunt had a magnolia tree in front of her house, and I’d think, What if I made the leaves into shoes? I’d find leaves and spend all day making shoes out of magnolia leaves. And then I’d sell it to her. That creativity sort of got capped at home. I felt the pressure to be successful because my parents had sacrificed so much in their entrepreneurial struggles in ’80s and ’90s Harlem."

The universal first-gen disappointment: not becoming a doctor (or lawyer)

I babysat for free in my building when other parents were working—sort of like a Harlem Baby-Sitters Club—and decided that maybe I could be a pediatrician. I’ll never forget my parents’ faces lighting up when I said that. They were so proud, and I loved that feeling. I loved fashion and beauty but told myself: No, there’s no money there, and I already told my parents I’d be a pediatrician.

I took my first statistics and pre-calc classes, saw the chemistry and lab classes where we had to dissect guinea pigs, and thought, I’m not doing this.

I told my parents by sophomore year that this path wasn’t for me, and they were devastated. My mom was praying and fell to the floor crying. Why do you always disappoint me? Why do you do this to me? What do you mean? You’ve wasted our lives.

It was a big, stressful moment. It was the first generational decision I made that broke my parents’ hearts, but one I knew was right for me. I would’ve been miserable if I stayed on that path. I literally failed stats. Career-wise, I eventually found my way, but it took breaking my parents’ hearts that first time to finally gain their trust that I knew what I was doing.

I ended up graduating with an English degree from Syracuse and studied abroad in Paris, a program that studied the literary greats: James Baldwin, Langston Hughes, Josephine Baker. People who took art and language and made a career out of it. That experience showed me that you could turn storytelling into a life. It was the first time I really believed I could, too.

In college, I worked at Sephora. I was the dorm room girl doing everyone’s pregame makeup: the lashes, the purple eyeshadow, all of it. I always had that knack, and being a salon baby, I was always around women talking about beauty and about showing up as their best selves.

After college, I worked at Rebecca Minkoff and Temptu, worked backstage at Fashion Week, and eventually graduated into L’Oréal, doing social media marketing and campaigns. Then I landed a dream job at Glossier doing product development.

The “anti–French-man-telling-us-what-to-do approach” to beauty

It was a big gamble for Emily Weiss to bring me on. She knew my strength was storytelling and using social to connect with people around beauty, and she wanted me to bring that strength into product development.

But Glossier was going through its “big girl” phase and I eventually got laid off. They brought in all these executives from Estée Lauder and essentially cleaned house. They looked at me like, Girl, you’ve never done PD before, but you’re a PD and innovations manager? You gotta go.

I was there for maybe a year and a couple months. It wasn’t long, but it was such a transitional year for them that it felt like ten. It was hard. I was learning on the job. I was learning how to create briefs, how to create products, understanding chemistry, how much retinol dispenses per pump, how to use the right component delivery system.

It was the perfect time in my career. I was a single girl in New York City, fully devoted. It was heartbreaking to get cut but it also taught me something important: I really loved product development. I loved not just talking about beauty but making the beauty we talk about.

I don’t even think I told my parents I’d been laid off. I used a little bit of my severance to go to Thailand and sit with myself. The universe was clearly telling me that this wasn’t mine. And honestly, no one has a great job when they’re not doing a good job.

But I was still high off the possibility of what Glossier represented. It was one of the first disruptive brands doing the anti–French-man-telling-us-what-to-do approach to beauty. It democratized beauty and there was still so much room left. I knew there was a multicultural element missing. I knew there were different skin tones, textures, and finishes that still weren’t being told in an elevated and accessible way. Why not raise my hand for the job?

Being dark-skinned, I knew the challenges that came from walking into Macy’s and not finding the experience we created at Glossier. I wanted to make beauty fun and less serious. I had a list of problems I wanted to solve, and the love, passion, and energy to do it. Ami Colé was born from that clarity. From knowing what was missing and what I never wanted to repeat.

On her symbolic semi-firstborn: Ami Colé

Ami Colé launched in 2021. We built a non-toxic, clean brand that celebrates melanin skin. From storytelling to the photoshoots, to the photographers we used, to the lighting, the retouching, the formulas—every detail was considered. And it took off faster than I ever imagined.

I went from traveling to Thailand with a dream to, 16 months later, being in 250 Sephora stores and online, winning over 80 awards, including five Allure Best of Beauty Awards in just four years. It was a whirlwind. We kept running and running. Fundraising, fixing what broke along the way. But at that kind of speed, unless you already have a solid infrastructure, it’s really hard to keep up.

And on top of that, the climate was tough. In 2019, only 0.4% of venture capital went to women of color. That number jumped to 1.6% during Black Lives Matter, which sounds like a lot, but is still almost nothing. It literally doubled and still wasn’t even 3%. In 2025, that number is down to 0.2%. It’s actually worse than it was in 2019. Yes, there’s economic instability, but what happens in that world is that people who already started under-resourced get hit the hardest. Between tariffs, social shifts, and the economic climate, everything compounded. We just didn’t have enough time to get the business model where it needed to be.

So this year, 2025, in July, I decided the best thing we could do for ourselves and our customers was to put the pencils down, to pause and set the brand up to be reimagined. The way we were doing business just wasn’t sustainable.

And yet: I’m really grateful. While it was sad to come to the end of that chapter, I truly know it’s just the beginning. I’ve learned so much and I’m still excited about the industry. I’m fascinated by how beauty evolves, how the economy works, and how culture intersects with it all. I’m excited about the next chapter. It feels like the first day of school.

"In 2019, only 0.4% of venture capital went to women of color. That number jumped to 1.6% during Black Lives Matter, which sounds like a lot, but is still almost nothing. It literally doubled and still wasn’t even 3%. In 2025, that number is down to 0.2%. It’s actually worse than it was in 2019."

A house filled with noise is a very, very fortunate one

I commend children for saying when they’re hungry or tired. They know exactly what they want and have the confidence to say it out loud. I’d be even more powerful if I had that kind of permission growing up. As a first-generation kid, it’s tricky—my parents gave me the incredible gifts of grit and tenacity, but there’s so much I have to unlearn, too.

If I was walking with my mom to school, everything felt rushed. Everything was urgent. Don’t touch the grass. Don’t play in the dirt. Your hands are dirty. Pow-pow. Mornings are still chaos, but I carve out time on weekends for my kids to take off their shoes, run on the grass, put their hands in the dirt, and just feel what that is. My mom would never have done that.

When I’m totally overwhelmed, I remind myself: a noisy house is a happy house. When they’re running around, yelling, being silly, even when my nerves feel fried, I take a breath and think, they feel safe. They’re happy. They’re not masking anything. I built that. I’m proud of that.

The biggest lesson I’ve learned from these past four years as a mother and an entrepreneur is: don’t let anyone put you in a box. I’m not just a Black founder. I’m not just a female founder. I’m many things. I’m an artist, a creative, an entrepreneur, a mother. All of these parts make up who I am, and I pray I can raise my kids with that same freedom.

"The biggest lesson I’ve learned from these past four years as a mother and an entrepreneur is: don’t let anyone put you in a box. I’m not just a Black founder. I’m not just a female founder. I’m many things. I’m an artist, a creative, an entrepreneur, a mother. All of these parts make up who I am, and I pray I can raise my kids with that same freedom."