What will my daughters remember?

Words By Gabby Lester-Coll

When I think of my mom growing up, I picture her at a dinner party. Not one dinner party in particular. In fact, I’m not sure if these dinner parties have actually happened, but I see our large wooden table and mismatched glassware and adults filling each chair. Scraps of food and smeared sauces on each plate, forks and knives scattered in different directions, crumpled up cloth napkins discarded off to the side.

My mother is sitting at the head of the table, slightly reclined, all eyes glued on her. She speaks, pausing for effect to add weight to her words, allowing ample space for everyone to savor and digest. Her hands are dancing in the air alongside her face and they stay there, suspended, throughout her pause, held up by stone pillars of confidence.

When I think of my mom growing up, I think of car rides with my brother next to me, my head leaned against the glass window, the radio too loud to speak. Her swerving the car and pumping the brakes to make us laugh. Our eyes locked from time to time in the rearview mirror. When they do, she sticks out her tongue.

I think of her getting ready for late night meetings and dinners and dates. I’m laying on the bed in her room with my legs pressed up against the headboard, my feet dangling in the air. She’s putting on dangly beaded earrings with missing beads by the one lamp that’s turned on in the room—she doesn’t believe in overhead lights—leaning so far forward I imagine the imprint of her shiny cheek against the mirror before she switches to the other side.

My stepfather is blasting Jazz in the other room, and the sound of my mom opening and closing bottles and drawers blends with the trumpet and trombone.

She puts Clinique body lotion on her shaved legs and too much blush on the apples of her cheeks. When she puts on her heels, the sound echoes into the corners of the high ceiling. She stomps so hard I stare at her footsteps, certain she will leave a trail of cracks in the hardwood floor behind her. I wait for the dark red kiss she leaves on my cheek before hearing the click of the brass door knob.

When I think of my mom growing up, I think of missing her. Of needs that could never be met. I think of the scent, the trail, the chase, of how big and dark and empty the house felt without her.

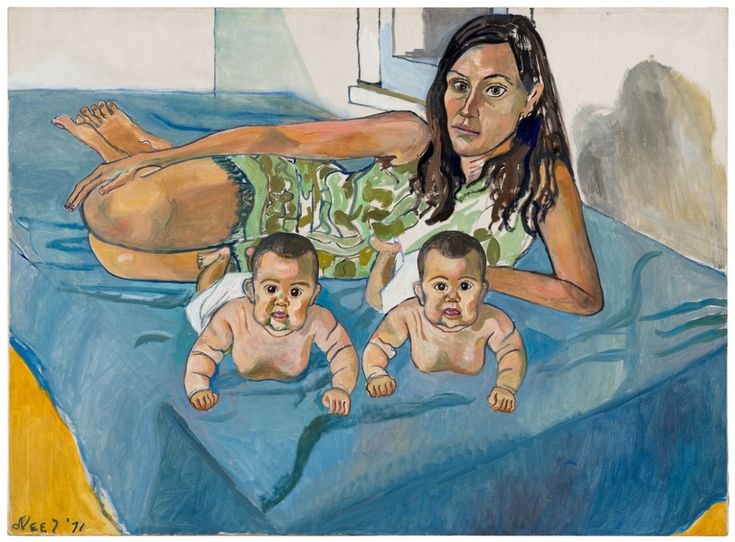

A year or so ago, I was in our kitchen making dinner, with Rafa and Paloma coming in and out from the playroom to ask me for things: to help them build something, to play kittens with them, to help them get dress up clothes on, they were hungry, they were thirsty, was I done yet?

In between requests and stirring pots I took a sip of red wine and looked out the window, overgrown with trees so large we could no longer see the sunset. I wondered, for the very first time, how the girls would remember me. Not me necessarily—no`t who I was as a mother or my personality or my heart or soul, if that is even something they get to know, and god I hope they do—but how they would remember our memories together. The kind of scenes their minds will create from bits and pieces of all the combinations of these exact scenarios that have happened so many times. The ones that are more real than the ones we forget.

If memories belong in the past, maybe these aren’t memories after all. Maybe it’s a parallel universe we close our eyes and step into in order to remember the essence of each other.

I wondered if this, me in the kitchen making dinner, will be the universe the girls step into when they think of me.

The garlic and onion crackling on the stove.

The sounds of lids and ladles and water running and cabinet doors opening and closing.

Nag champa burning in the other room.

What did I smell like to them?

Do they see how tired I feel?

If they close their eyes will they hear the sound of my hushed voice in the other room sending voice notes?

The slices of dusty light spilling onto the floor in reds, oranges, and pinks, before our household goes dark with the world around it.

I reach, on tippy toes, into our shell lantern, to turn on the one lamp in the room. The sound of seashells clang, a warm light emanates from the corner.

Turns out, I, too, don’t believe in worlds with overhead lights.

I wonder if they won’t either.

Gabby Lester-Coll is a full spectrum doula, writer, and brand marketer living in Rincon, Puerto Rico with her husband, two baby girls, Paloma (5) and Rafaela (3), and their one too many cats. Her Substack newsletter Yayas explores birth, motherhood, and parenting through personal stories that explore the powerful, painful, transformative work it is to be a mama. Drawing inspiration from the Taino word "Yaya" (creation, life-giver), she writes from experience as a homebirth mama and doula who's walked the path herself and guides others in claiming their journey into motherhood. She loves spending slow time in nature with her family, spends all week looking forward to hip hop on wednesdays, and is hoping to learn how to sew this year.