Searching For Our “Baby Mama”

Words by Ruthie Ackerman

I’d already spent years online dating, scrolling through profiles of strangers searching for something, anything, that screamed: he’s the one. So when my fertility doctor dropped the bomb that my husband Rob and I would need to use donor eggs to have a child, I tried to imagine what awaited us inside the database of women who I’d come to think of as my replacement.

It took months of blood tests and invasive procedures to make sure my body was ready before our clinic would give us the coveted code to access the pool of women whose 23 chromosomes could become half of the building blocks of our child. Behind a locked door on my computer, the woman who held a portion of our child’s DNA deep in her body waited. The woman I jokingly referred to as our “baby mama.”

Intellectually I knew that our donor would not be our child’s mother–that title would be held by me, the person cleaning diaper explosions on the sidewalks of New York City and waking up at 3am to wails that sounded like fire engines racing to put out a deadly blaze–but still, the absurdity of our whole situation was not lost on me. Choosing a donor felt like dating on Tinder except if everything went right, I wouldn't gain a husband, but a batch of eggs, one of which would hopefully become our child someday.

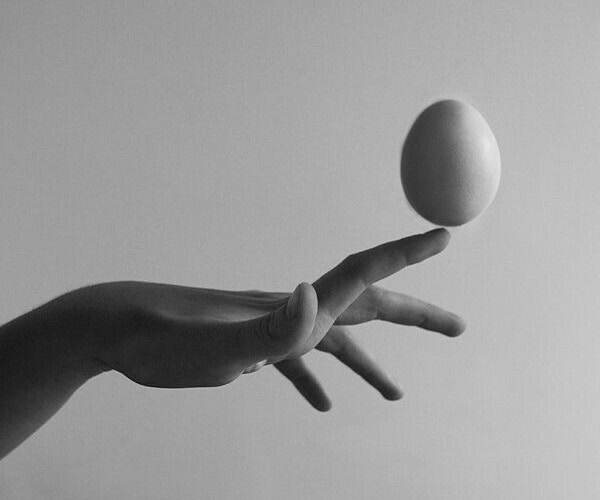

Our fertility doctor tried to make the whole donor thing sound like it was no big deal. “An egg is only one cell,” he said. “Your body will decide how the baby’s genes are expressed. Your blood will flow through the baby’s body.” But I didn’t know anyone who had used donor eggs before. Not only that, I’d never even heard of them.

The first night we opened the donor database, Rob and I were sitting in a dark bar with beers in hand, knees touching under the table, laptops open. After a few minutes of silence, Rob pointed to a profile and asked, “What about her? She has a clean medical history and her genetic tests look good.”

I shook my head, wondering what about her Rob liked. “She looks nothing like me,” I finally said. My fear was that if our kid didn’t resemble me, that everyone would notice, my failure imprinted on our child’s face. The other thing I feared: choosing the generation upon generation of molecular history our baby would carry.

We kept scanning through the donors’ photos. Some clearly posted the same pictures they used on Bumble or Hinge, their head tilted to the side, wearing a low-cut dress. One even had a picture of herself in downward facing dog on a deserted beach. Her profile screamed, “Pick me! I’ll make all of your motherhood dreams come true!”

" Choosing a donor felt like dating on Tinder except if everything went right, I wouldn't gain a husband, but a batch of eggs, one of which would hopefully become our child someday."

I’d gone out on enough shitty first dates to know that people lied in their profiles. They looked nothing like their photos. They twisted and cherry-picked the truth about their lives to make themselves appear better than they were. The ridiculousness of trying to choose our child’s unique genetic signature from a few photos of a stranger as a baby and an adult, a short essay, and answers to a series of inane questions like “What would you bring with you to a deserted island?” overwhelmed me. The fact that I wanted to be pregnant yesterday didn’t help.

The majority of the women we scrolled by were just plain wrong. If Rob and I had had a one-night stand and I’d gotten knocked up that first time we had sex, we wouldn’t have had a choice as to which genes to use. Our chromosomes would have combined in mysterious ways, and when our baby popped out, we would have marveled at how his eyebrows looked like rainbows just like Rob’s, or how the shape of her face was a mirror image of mine. But now, here we were, being asked to choose the clay from which our baby would be molded. I didn’t like playing God.

The first thing that struck me, after I got over the fact that Rob and I were swiping on women as if we were perusing a dating site together, was just how few donors there were. My nurse reassured me that new donors were being added every few days, but the reality was that there were only about three dozen profiles. By the time we filtered those down to the women who looked even remotely like me—brown curly hair and brown eyes—there were less than ten. The truth is that I was looking for someone who looked familiar. And familiar, in my eyes, meant Jewish. The donor didn’t need to be Jewish, but since I’m Jewish, I hoped she’d at least look Jewish. That night on the train ride home, Rob and I decided to keep checking for new donors every few days.

Which is what we did. And then a few weeks later, as I lay across our uncomfortable couch long after Rob fell asleep, there she was. She looked like she could be my cousin. Brown hair, brown eyes, high cheekbones, wide smile, 5’6”, 142 pounds, just like me. When I saw her profile, I thought: this one could work. But I didn’t trust myself. What if there was someone better waiting just around the next corner? This didn’t seem like a decision I should rush into.

"The ridiculousness of trying to choose our child’s unique genetic signature from a few photos of a stranger as a baby and an adult, a short essay, and answers to a series of inane questions like “What would you bring with you to a deserted island?” overwhelmed me. The fact that I wanted to be pregnant yesterday didn’t help."

Suddenly, my heart ached for all that would be lost by not using my genes. I’m funny. Is that genetic? Or how about my square-shaped face that I always attributed to my Eastern European ancestry? My genes aren’t perfect, but at least I know what my genes hold (for better and worse).

Over the next couple of days, I stayed up lurking in Facebook groups for donor egg recipients. The women in these groups talked about everything. “How did you choose your donor?” I typed. And then closed my laptop.

By now I’d named the donor who looked like my cousin, Rachel, not her real name (!), because it was a bland enough, Jewish sounding name. The next time I opened my computer, I heard a ding, letting me know I received a reply to my message from the Facebook group. “Look for someone who you’d want to grab a coffee with, someone you’d want to get to know,” a stranger typed. “No more and no less.”

That seemed like good advice. So I scrolled through all the profiles in the database again, imagining sitting at Joe coffee in my neighborhood next to each woman. Are you coffee-worthy? And how about you?

"The first thing that struck me, after I got over the fact that Rob and I were swiping on women as if we were perusing a dating site together, was just how few donors there were. My nurse reassured me that new donors were being added every few days, but the reality was that there were only about three dozen profiles."

The next day I told Rob about Rachel. “There’s something about her,” I said, stabbing at my screen. He looked over, pulled her profile up on his screen too.

“What is it about her that you like?” he asked, curiously. I didn’t know how to answer his question. I still don’t. I felt a click, a sense of connection, a “this could be it” feeling. “She seems like someone I’d like to have coffee with,” I finally said.

We didn’t make any decisions that day. Over the following weekend we spoke to our doctor who told us that Rachel was a first timer, meaning there was no data to give us a sense of how many eggs she might produce. He recommended going with a “proven donor.” But I was certain about Rachel.

I didn’t want to disappoint our doctor by going against his advice, though. Wasn’t he the expert? Isn't that why they gave him the white lab coat? I also didn’t want to not get pregnant and then have our doctor and Rob say: “We told you to go with another donor.”

Then again, I knew that if I didn’t choose the one my gut told me to and then I miscarried or never got pregnant in the first place, I would hate myself for not having listened to my intuition. There are some decisions that just aren’t rational. And this was one of them.

I’d spent so many years distrusting my deepest desires. I hadn’t been certain I wanted a child. I wasn’t sure if I’d be a good mother. I didn’t know whether to attempt to have a baby on my own or find a partner. And now with this most personal–and precious–decision, I could finally hear what I wanted. And her name was Rachel.

After many more days of discussion, Rob agreed that if I felt good about Rachel then he did too. As long as she had no medical or genetic concerns he was on board. “Call the clinic and tell the nurse,” he said, squeezing my hand gently. “I won’t stand in your way.”

Five years later, our daughter has just entered kindergarten. I still look back on that moment we chose our donor and smile. For one of the first times in my life, I listened to my own voice. For one of the first times in my life I made a decision just because I felt it was the right one. For one of the first times in my life I didn’t try to people-please and pretzel myself into distorted shapes.

I followed my heart and it didn’t lead me astray.

An award-winning journalist, Ruthie Ackerman’s writing has been published in Vogue, Glamour, O Magazine, The New York Times, The Atlantic, The Wall Street Journal, Forbes, Salon, Slate, Newsweek, and more. Her Modern Love essay for the New York Times became the launching point for her memoir, The Mother Code: My Story of Love, Loss, and the Myths That Shape Us. Ruthie launched The Ignite Writers Collective in 2019 and since then has become an in-demand book coach and developmental editor. Her client wins include a USA Today bestseller, book deals with Big 5 publishers, representation by buzzy book agents, and essays in prestigious outlets. She has a Master's in Journalism from New York University and lives in Brooklyn with her family.