My mother fled Iran. Her firsts stayed behind.

Words by Shideh Etaat

If you’re a child of immigrants there’s always a story that lives inside of you. For as long as I can remember, mine has been — RUN. My parents and two-year-old brother had to escape Iran during the 1979 Islamic Revolution and subsequent war. Except it was too late for airplanes. They had to flee on horseback in the middle of the night through the mountains that connect Iran to Turkey.

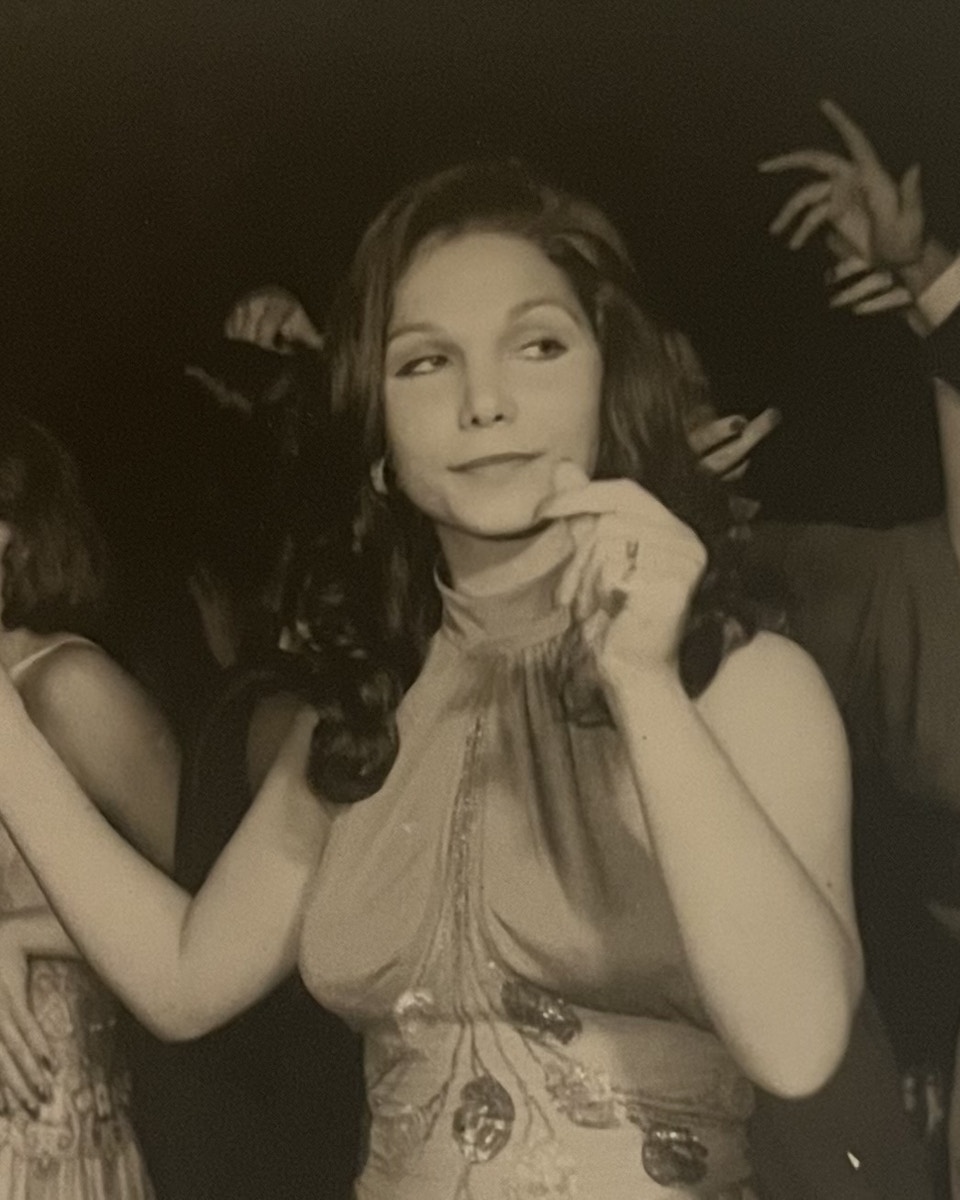

My mother, an incredibly well dressed, elegant woman, had to leave all her clothes and things behind. She could only bring a bag of diapers for my brother. Never having ridden a horse before, she had to sit on one with no saddle and kept sliding down as they navigated the bumpy terrain.

It’s only the complete undoing of a place and the terror projected onto its people that would push someone to take such a journey, I think. The Iranian people were fighting for democracy and once they ousted the king, which was no small feat, they got a theocracy instead. A leader, Khomeini, who cared more about some extreme version of Islam than Iran. To put her own life and the life of her child at risk for the great unknown means that what was — a country overtaken by religious fanatics — and what was becoming — a country crumbling from war — became an unbearable idea, so dismal, such a threat to freedom, to life itself.

They had to run from the big, bad, terrible thing that was after them. They had to run from the home they once loved, one that was now disappearing overnight, towards hope, towards better, towards the wild unknown laid out before them. They dressed like Kurdish villagers to lessen suspicion. Puffy lace, glittering skirts, baggy pants, round hats.

At one point, my mother had to cross a river that had gone wild, their paid guides trying to help her get to the other side. She handed my brother to their guide and told him if anything happened to promise he would take care of her baby.

"My parents and two-year-old brother had to escape Iran during the 1979 Islamic Revolution and subsequent war. Except it was too late for airplanes. They had to flee on horseback in the middle of the night through the mountains that connect Iran to Turkey."

I imagine what the terror must have felt like, lightning bolts sending a buzz throughout her body — the primal need to survive electric, shooting through her while her heart ached at the thought of never seeing her child again.

I might die here, she must have thought, and will it be worth it in the end?

How many mothers have had no choice but to cross such terrain, have made this same impossible decision, have offered to sacrifice their own life to make sure their children could not only survive, but live better than they did?

My mother speaks of this story like the plot of a dramatic movie instead of the lived trauma that it actually is.

"How many mothers have had no choice but to cross such terrain, have made this same impossible decision, have offered to sacrifice their own life to make sure their children could not only survive, but live better than they did? "

Once they finally arrived in Turkey, clothes torn in shreds, skin scratched, bloodied and bruised, they walked straight into the Hilton hotel and asked for a room. Of course they were rejected, told there were none. But my father put down a wad of cash.

“Then give us the suite,” he said.

And of course they did.

My mother says she took a bath, drank cognac and smoked a cigarette while the hot bubbles soaked her torn up skin.

“It was the best night of my life,” she always tells me. The relief of living after the possibility of death. I wasn’t there, I didn’t ride the horse or cry when my mother handed me to a stranger, or breathe the tense air or break bread with the Kurdish villagers, but somewhere in my body I know this is a part of my origin story too.

Run.

Run.

Run.

The opposite of run then could be thought of as — Stay. As lay down roots, as allow yourself to be carried and held by a place. For me that place has always been Los Angeles. A lot of Iranians ended up here for a variety of reasons. My family already had family here waiting for them. It was a soft place to land. And no matter where I have lived and traveled to in this world — LA has always found a way to call me back.

And now I’m 40 and my six-year-old son has fallen asleep in the car on the majestic canyon that stretches from The San Fernando Valley to Malibu. He’s too old for afternoon naps but he slept at my parents’ house the night before and for some inexplicable reason was up in the middle of the night. Now I’m forcing him to nap, intentionally taking him on this hypnotic road.

I park the car in the Malibu Bluffs parking lot, a little park across from Pepperdine University that overlooks the ocean. I’ve been coming here since I was a little girl. I finally wake him up because too much sleep will also make him an unhinged little boy. It’s a struggle, this transition between dream state and wakefulness.

“Carry me,” he says, and even though he’s too heavy for all of this, I do. Because it’s a gorgeous day and I want to go look at the ocean. He’s half asleep, half awake and I’m doing my very best to keep him afloat, to hold him securely in my arms and make sure he doesn’t slide down.

Another mother passes by, nods in acknowledgement.

“Another Super Mom,” she says. As if it’s a secret handshake only mothers know, this understanding, this silent code that we become the strongest versions of ourselves in order to mother.

We finally land on a picnic table overlooking the ocean and sit up on the table itself. It seems like the ocean sounds send a wave of energy through my son because his eyes are wide now and a small hint of smile appears. It’s winter but sunny which means we can sit here with our sweaters on and not feel cold. We bundle up together and watch the ocean in all its brilliance.

A thought I don’t expect creeps in, a memory, a moment, a first. I don’t say it out loud, only to myself.

This is the exact spot where I had my first kiss. This picnic table. This one, right here. The one we’re sitting on.

His name was Phil, he was a tall and beautiful biracial senior headed for college and I was an inexperienced and eager junior on the brink of being a senior with no greater desire in the world than to be kissed. It was the summer of 2001. We came to this park, to this table at night.

I don’t tell my son this story, but I’m grateful it exists and one day I certainly will. But as I watch the ocean in its enormity, I can’t help but think about my mother and all her firsts I will never see.

The street corner where she had her first kiss, the first apartment she ever lived in, the high school where she smoked her first cigarette with her friend.

Both my parents have impeccable memories when it comes to their youth in Iran. The level of detail, their ability to tell a story, it always amazes me. When your home is stolen from you, when you’re exiled from it for forty-three years and can never go back your memories are the only thing you feel like you belong to, and so you remember. You remember really fucking well.

I want to cry and I want to laugh and I want to squeeze my child and let him run free all at once. I’m sitting on a picnic table with him but I’m also sixteen and kissing a boy who will immediately disappoint me after this kiss and never call me again after that night and I’m holding hands with my mother as we walk through Tehran and she points out all her firsts to me.

"Both my parents have impeccable memories when it comes to their youth in Iran. When your home is stolen from you, when you’re exiled from it for forty-three years and can never go back your memories are the only thing you feel like you belong to, and so you remember. You remember really fucking well."

This is the building where I had my first job.

This is the restaurant where I went on my first date with your father.

This park is where I took your brother out for the first time after he was born.

LA is so expansive and vast that it’s hard to always feel your belonging, but I know this ocean is my home, these mountains, these canyons, this energy of always dreaming. This is the home my parents created for us and I’m grateful for it. After a journey of exile and escape not everyone gets to land somewhere so softly. And how beautiful that I’m raising my son here, that he will see and know my firsts. That he will feel deeper and deeper roots than I ever did.

My son is bored now because he can only stare out at the ocean for so long. So we get up and as we do I take one last look. I can’t help but wonder if my mother paused at all somewhere on her journey, somewhere in between slipping off that horse, in between the lightning bolts of fear traveling all the way to her fingertips. I wonder if she even got the chance to look back, one last time, if only to let her body swallow up all her firsts, to make sure no piece of her got left behind.

Shideh Etaat is a LA based mama and writer with roots in Iran. Her first novel Rana Joon and the One & Only Nowwas published in 2023. She is also founder of Aramesh Well Being where she does one-one life coaching and leads women’s groups with the intention of processing through writing and the magic of being witnessed.