First sobriety, then suburbia

Words by Emily Barasch

When I started dating my now-husband, he presented his desire to live in the suburbs eventually as a red line. This was not a passing preference but a non-negotiable. An adept practitioner of magical thinking, I perceived this not as a fixed point but as a challenge—one I could erase with charm, persistence, and the sheer force of will.

Born and raised on the Upper West Side, the city was my blood. My short five years away for college and a job in D.C., a blip. The city gave me life; I found it cute, stimulating, and vital. The noises and smells, noxious to many, were ambient and relaxing. Every day, something deliciously familiar and dazzlingly new. Like many a cringy millennial who grew up on Carrie Bradshaw, the city was a central character in my life whose sometimes unsavory behavior I could excuse with ease.

The only thing I was more besotted with was this guy. I found a man with whom I could be completely comfortable with, who made me howl with laughter. Handsome and smart, he didn’t care that I had struggled with my mental health and got sober in my early twenties.

This should be a given, but my experience dating as a young sober woman had taught me otherwise. There was the one guy on a second date at Eataly, as we walked past prosciutto racks and cases of braciole, pressuring me to tell him why I chose to abstain. Mildly hungry and massively miffed, I shared a little and only in vague terms. He looked down, looked at some tomato galettes, and then looked back up at me. “I’m sorry,” he said. “But my ex, ex-girlfriend—” that’s right, two girlfriends ago, “was bulimic and I really don’t want to deal with taking care of someone like that ever again.”

There was the painter I saw on and off for several months, so absorbed in his own mythology that one night, he forgot I was sober entirely and casually offered me cocaine. (He was so hot. I was a baby. But I still said no, thankfully.)

Shortly after I met my husband, it was my two-year sober anniversary. He brought cupcakes, balloons, and flowers to my apartment. His tone was the right combination of solemn acknowledgment and hearty cheerleading. He didn’t make me feel like a freak (which I did, always, and is probably why I used to begin with), but strong, healthy, and worthy of celebration.

I fell in love for that reason and about a million other ones. So I said I’d do the backyard, the mini-van, and the mortgage in exchange for a ring, babies, and forevermore.

"I fell in love for that reason and about a million other ones. So I said I’d do the backyard, the mini-van, and the mortgage in exchange for a ring, babies, and forevermore."

*

The city had offered me an opportunity for reinvention in sobriety. Instead of partying, being sad, and bedrotting, I ate, I gabbed, I beep bopped around town. I found God, or at least a group of orderly (female) drunks, at an all-women meeting in the same Greenwich Village church where they shot the last scene of Lady Bird. I went to a space on West Houston on top of a bar that held meetings 24 hours a day. I spotted celebrities and queer icons and busboys and business-people and designers and artists and old-school Beatniks all trying to get and stay sober.

I ate sushi everywhere, Pinkberry on 14th street, and pancakes in Gramercy diners with other sober women and gay men. Talking, talking, talking in Via Quadrono, the greatest restaurant on the Upper East Side and maybe the world, more Indian food in Curry Hill, and vegan food that made my belly ache almost as much as the laughter. There was the Greek restaurant with the largest salads I’d ever seen, I was so hungry in early sobriety I’d eat pieces of leaves and feta cheese in lumps with my fingers, plunking olive-oil soaked warm pita into hummus, slurping club sodas with a splash of cran. Walks down the Hudson River, into Washington Square Park amongst the stoners for whom I had at first so much jealousy and contempt for and then complete neutrality. There was coffee too, so many coffee dates. I’d never felt more popular, not realizing people wanting to get together was a part of the program, that they were reaching out to me to help themselves.

There was also a sort of New Yorker superiority complex that kept me buoyant. My life could suck—which was at times how I felt about getting sober and the circumstances that led me to it—but at least I lived in the greatest city in the world. New York was the Face Card that didn’t quit, an expanse of pure vibes: art, food, and people-watching that could soften many blows.

*

I had six years of sobriety (and relatively good mental health) when we had a baby. We chose the Upper West Side as our landing pad. Early motherhood, especially with the first, tends to resurge unearthed memories of your own childhood. Raising a child where you were raised only adds to that sensation. A fascinating part of my sobriety has been reconnecting with my child self. My pride and happiness with how far I had come and experiencing that in my old home created a pair of rose-colored glasses, the lens I came to experience the UWS.

It was still the city but, in that neighborhood, there was a slowness, an oldness. Every corner I turned I wanted to take a picture and etch into my mind: Emily’s Version of Beauty. Bagels and schmear and cherry jam in yogurt all over his highchair. The park, only a block from our apartment. Each season brought new delights. Just as I met female friends in sobriety who put me back whole, the mother friends I met in the park did the same. Where did I find my Higher Power? In this one century-old tree on 79th Street that made me feel like there was something bigger than me, designing a universe capable of beauty, justice, and kindness.

So yes, I was prone to romanticizing the many moments of our UWS time. My husband, less so. Plugged into his Citizen app, he’d alert me to crimes large and petty. He didn’t appreciate parking in the city, the Central Park crowds, or our cockroach roommates who would emerge during the summer. But it was more than normal city grievances. I had made a somewhat obtuse mistake: I took his acceptance of my brain’s history to mean it wasn’t something he thought or worried about. But he did, often, especially in the context of our kids (within our first year on the UWS, we were pregnant with our second) and the reality of the genetic nature of these diseases.

"The city had offered me an opportunity for reinvention in sobriety. Instead of partying, being sad, and bedrotting, I ate, I gabbed, I beep bopped around town. I found God, or at least a group of orderly (female) drunks, at an all-women meeting in the same Greenwich Village church where they shot the last scene of Lady Bird. I spotted celebrities and queer icons and busboys and business-people and designers and artists and old-school Beatniks all trying to get and stay sober."

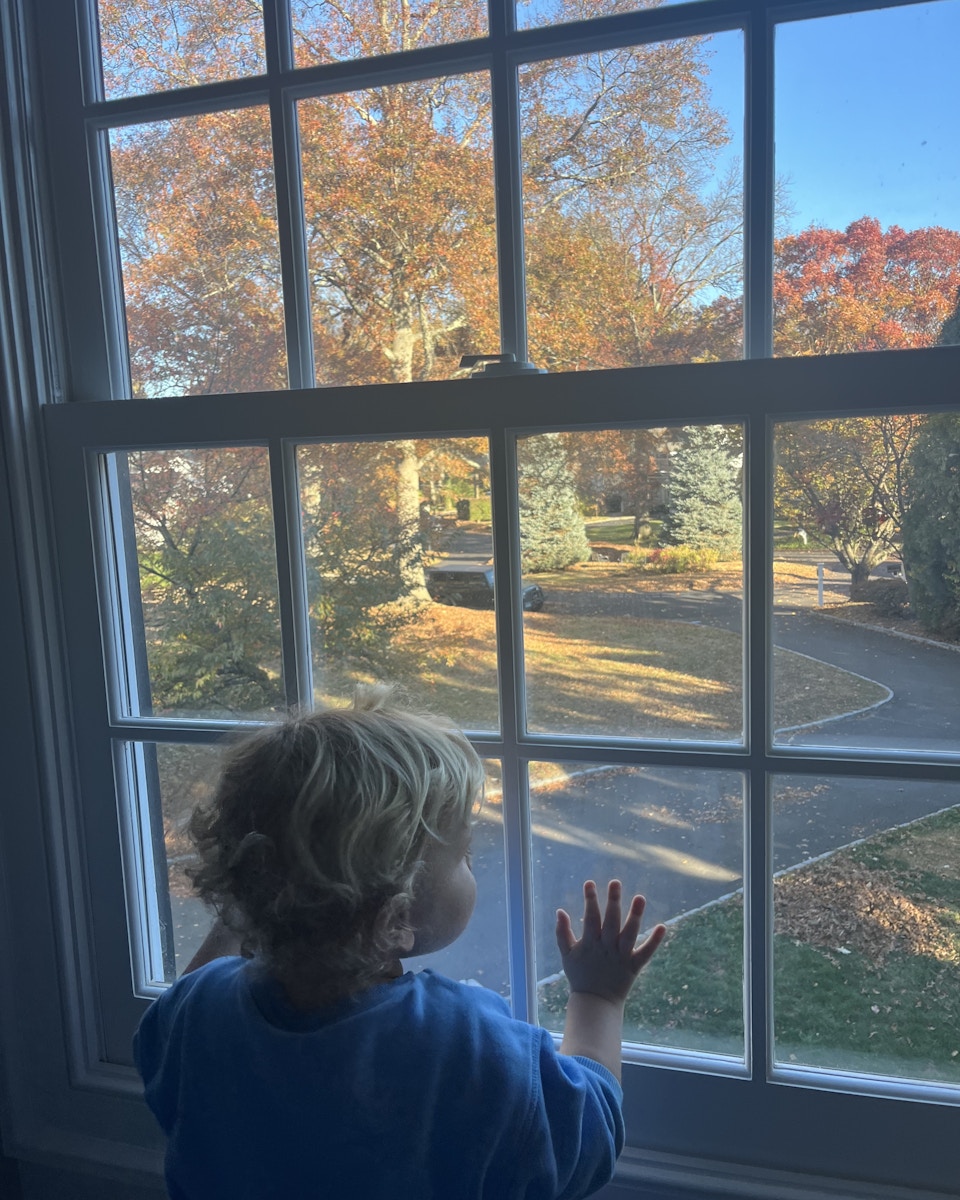

Once we had a child, his desire to move out of the city reemerged. He believed that more time outdoors meant better health, mental and physical. I couldn’t imagine my boys spending more time outdoors, park rats that they were, but the point was taken. In my inbox came a story about how outdoor childhood independence leads to better mental health and then, another, how over-stimulation is bad for mental health. There was a podcast about how putting your face into sunlight and feet into grass makes your brain less noisy. There were many conversations about the way city kids grow up quickly—a topic of conversation that may trigger your friends who grew up in the burbs. We smoked cigarettes, too! They’d say. Yeah, we know!

Alongside the heady stuff was the reality of our situation. Two boys born within 18 months, teeming with energy and stuff—clothes, toys, gear. The more I grew into motherhood, the more I discovered my own preferences around it and one of them was that I found being outside with them pleasurable, indoors with them at times maddening. I fantasized about a basement where we could put our shit. A backyard where I could let my own personal freak fly while they played appealed to me, versus in New York where you never knew who you’d run into which led me to questionable decisions like loafers in the park.

And fuck it, I’ll say it: If I could make any decision that would lessen the odds of them developing my mental illness and/or addiction, even if I were decreasing the chances by a fraction of a percentage, I’d make it three million times over. I’d make the decision knowing it was affording me a sense of control over and an added layer of confidence on something that scared me a lot, even if I ultimately knew it was perhaps an illusion, that nature could easily overpower nurture.

Losing your mind and getting sober in your early twenties is serious stuff; having two healthy energetic boys with a year and a half between them is most of the time profoundly unserious. Now they have their yard, basement, and soccer. We have our cackling fireplace we light for movie night, a public beach seven minutes away. The city, a short 55-minute train ride, waiting for me.

Emily Barasch is a writer who lives in Connecticut with her husband and two sons. She has contributed to Vogue, Romper, Violet Book, The Coveteur, Into the Gloss, and Hey Alma. She is also Head of Content for Seven Starling, a virtual maternal mental health clinic and has a Substack called The Mom News.