A Disembodied Mother

Words by Reema Rao

The first time I remember meeting my son was twelve hours after I birthed him via emergency C-section.

There’s a knock at the door of the room where I’ve just woken up. In here, the air smells manufactured and it’s dark, except for a single recessed light that reflects in the black of the window. Out there, it’s the sticky part of August and still dark – though I’m told it’s the morning and going to be a beautiful day. I feel neither here nor there. I push my palms into the bed to lift myself up, but only my legs move, and I wonder if this is actually what I intended to do. Maybe that’s why in here, over the next five days I will spend in the hospital, things just seem to happen. I am told what will happen, and I do it.

A nurse wheels a glass box into the room, careful to avoid the tangle of wires, shoes, and duffel bags cluttering the floor. She announces that the baby is hungry at the same time she tells me I need to take my meds. A plastic cup appears in my hand containing a cocktail of colored pills: Gas X to kickstart my digestion slowed from the anesthesia, Colace to ease my first bowel movement, extra-strength Motrin to relax the swelling where I’ve been sealed back up, and oxycodone for good measure. A different medicine to repair each unworking part of me. To be postpartum, I realize, is demanding my misshapen, mangled body to care for another outside of it, simultaneously.

The nurse takes the baby out of the box and places him in my arms. I don’t hear a cry. He doesn’t make a sound. Even if he did, I wouldn’t recognize it. I don’t even know what he looks like. This baby, he stares up at me with eyes peeled wide open. I feel it’d be a good time to cry. Proof of something deeper inside of me that knows this baby and claims him as mine. But my body doesn’t make the tears, even against the baby’s unflinching stare.

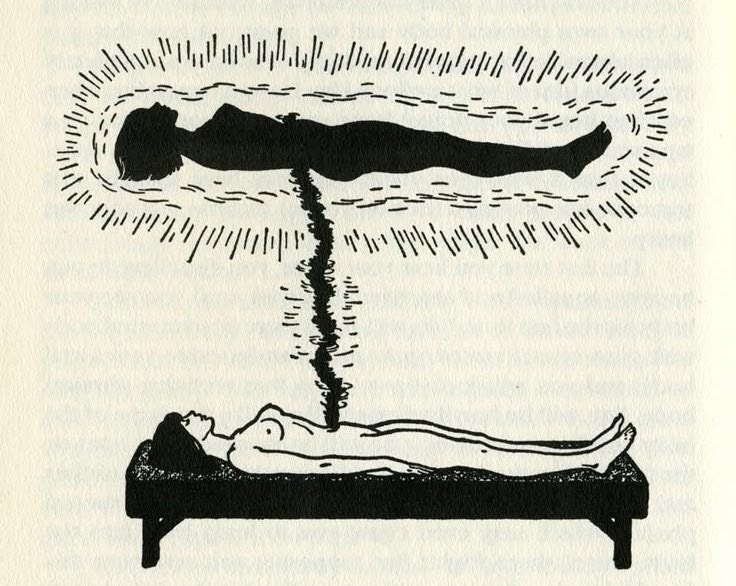

Later, my husband will tell me to scroll through the photos on my phone that commemorated our first meeting – baby and I – in the operating room. In the photos, it’s just his cheek to mine, instead of a full skin-to-skin embrace. My arms are taped down to the table like a crucifixion. Him tightly swaddled after being worked on by the NICU team and me in a surgical hair net. His eyes squinting in the bright light and mine soulless, from sheer exhaustion and being pumped with meds. It’s me in the photo, but it doesn’t feel like it. My body is there, but I am not.

The nurse tells me I need to try breastfeeding now if I want my milk to come in. I don’t really know what these words mean – “try breastfeeding” – and pray that my body does. I push my palms into the bed again, harder this time, and feel a sharp rip across my stomach. I don’t yet remember the cold metal of the operating table under my naked, shivering body, or the trash bags near my head for my insistent vomit, or the hands pressing bruises in my skin to stop the hemorrhaging. I don’t remember why I hurt. I will later, these flashes of reality coming to me in frequent, heavy doses. But right now, I just need to figure out how to feed the baby. I pull him towards my breast and hope he’ll know what to do. I reposition him several times so that his legs don’t rub the Frankensteined staples lining my low belly.

“Don’t worry Mom, it’ll take time to get used to,” the nurse says. She means the breastfeeding.

“But is it happening? Is it working?” I want to ask. The breastfeeding, yes, but also the rest of it.

I think about the quote I’ve seen on my Instagram feed all too often: “The day a baby is born, so is a mother.” What then, if I don’t remember my baby being born? Would I really know how to mother?

***

I was never the woman who knew she wanted to have children. Though after having my son, I often wished I was in fact that woman.

I imagined those who wanted children their entire lives always felt a deep instinct to mother – whatever that meant to each. I’ve been close to many pregnant women in my life, and in their ripe states, watched their skin stretch itself taut across their bellies and form fissures like cracks in the desert. They revered these changes, or at the very least, were at peace with them – the outward manifestation of something deeply complex and almost mystical taking place on the inside. I had also read that pregnancy chemically augments a woman’s brain, so much so that she can be considered an entirely different person after. Her biology will also remember every pregnancy, even those that end in loss, evidenced by remains of fetal cells in her body. But it wasn’t just that these women felt an instinct; rationalized or emotional, they trusted it, too. How often had I heard new mothers say, you just won’t know until you know. They believed their bodies would transform when called to. What a daunting thing to comprehend for someone who’d spent her whole life needing to know!

I dated my husband for nearly a decade before we got married. I relied on a color-coded shared calendar to track the happenings of our daily lives. Our vacations started to follow a reliable February and September cadence. I had a daily birth control alarm before we lived together and after. My period showed up every month on schedule. When we neared our 30th birthdays, we had “the talk” about children because it seemed like the right sort of thing to expect next. I didn’t know how starting a family would ever fit in this carefully constructed life of mine, but we decided to try. And just to be sure, I scheduled a fertility consultation first. If it wasn’t going to happen, I needed to know that, too. I would come to find that it would happen, and thankfully, easily.

Much of my hesitation around having children wasn't rooted in fear of how a baby might change me, but rather, a fear that I wouldn’t know how to change for a baby. Even midway through my pregnancy, I wondered aloud to my friends, How do I know if I’m really ready to be a mom?, my belly burgeoning and I having no choice but to believe it.

Unfortunately, my delivery would only validate my fear.

No one wants a C-section if they can help it. And despite knowing that one in three women end up in the operating room, I was sure I had the privilege and power to avoid it. I had insurance and close access to a large hospital system (what many called a “baby factory”); I consulted with a pelvic floor therapist and chiropractor weekly; I worked from home and had a highly-present partner; I found the energy and strength to stay active for most of my pregnancy; I watched all the Instagram reels about breathing techniques, birthing positions, perineal stretches, and how six dates a day could soften my cervix; I prepared “laboraid” to power me through contractions. I was readying my body for its greatest test, determined to be in continual lockstep with it, if not one step ahead. A C-section was not in my birth plan – not the one in my mind nor the one on paper.

In hindsight, I find the idea of a written birth plan indulgent. I don’t mean the notion that a mother should exercise her autonomy and the right to those decisions, but the falsehood of any control over our bodies in this process. As a culture, I believe we perpetuate a romanticized narrative that how and where one gives birth is indicative of the kind mother she’ll be and the bond she’ll have with her child. I picture homes with pools and candles, birthing rooms brimming with essential oils and instrumental crescendos, dimmed hospital lights and the gentle, rhythmic beeping of a heart rate monitor. For some, that beautiful birth story is a reality. But for me, and others like me, our true experiences don’t match the stories we’d pre-written for ourselves or our babies.

I labored for twenty seven hours and pushed for three – through failed epidurals, back labor, then stalled labor due to the baby’s malposition. I suffered an amniotic infection, which infected the baby, which forced us into a code blue, category 1 C-section. I hemorrhaged a liter of blood and the baby came out initially not breathing. After nine-and-some months of living in physical tandem, my son was swiftly cut from me in under sixty seconds.

In the only dark solace I could grasp at, I believed my son and I were still together – navigating the same trauma, just on opposite sides of the steel blue curtain. I reached for my husband’s hand, feeling a deep pressure and rummaging around where I guessed my abdomen was. Through my medicated high, I said, They’re taking him out now, he’ll be okay. My husband started to cry, He’s already out. What I was feeling was the doctors rushing to stop the blood loss.

Later, I will read a play-by-play of my delivery in the doctor’s post-op notes: After anesthesia, abdomen was entered via transverse incision. Rectus muscles separated…bladder blade was placed…bladder removed…uterus shifted. Vaginal hand was used to de-station fetal head. Fetus delivered. Bladder replaced, uterus replaced. Skin approximated with staples.

My body had been severed. And at times, quite literally, I existed completely separately from my body. From the baby, my son, too. Though I didn’t know it. I couldn’t feel it.

***

It’s somewhere between the blur of six-to-eight weeks postpartum, and I am crumpled inside our guest room closet. The lights are all on – bedroom, desk lamp, inside the closet too – because I’ve become too terrified of anything that resembles night. The world goes too quiet and it’s just us and the baby to fend for ourselves. When my husband finds me, pulling apart the accordion doors, it feels like I’m finding myself here too.

“I can’t put him down,” I sob. “I can never put him down.”

“Blow out the birthday candle,” my husband coaches me – an act meant to help me slowly inhale and exhale.

We are amidst a nap strike. The baby refuses to sleep anywhere but in our arms. But if it’s not a nap strike, it’s a difficult feeding session, and if it’s not feeding, it’s gas. And if not that, shouldn’t I have figured it out by now? Time feels stretched, endless, fruitless in this totally normal postpartum spiral. But the only place my spirals end are in the thoughts of how I must run away – for the good of the baby and the good of this family. I briefly think about how I’m not even healed well enough to run in this “run away” plan.

If I couldn't birth the baby – normally, vaginally, as planned, as expected – I surely couldn’t put him down for a nap. Or do much else that will be required of me. I would believe this for much of my son’s first months. I would look at him, growing and thriving, and repeatedly think there’s no possible way I had anything to do with it.

“Touch the carpet beneath you,” my husband continues. “Name five things you can see.”

I don’t touch and I don’t see. He appears to be wiping the tears off my face, a thumb swiping a u-shape under each of my eyes, but I don’t feel this either.

***

My C-section may have saved two lives, but it also led to so much loss.

I lost trust in the hospital as an institution, especially with its bias towards 24-hour deliveries, statistics, and surgical means to the end. I felt urged into a series of membrane sweeps, artificial water breaking, and Pitocin to rush labor. Along the way, I was told each had “very minimal downsides,” but no doctor ever gave me a clear or consistent explanation as to what happened in the end. I will always wonder if my C-section wasn’t a result of misguided interventions at odds with my body’s natural impulse. Is this where my “instinct” was compromised?

I lost any sense of joy and pride in my birth story the way others can share of theirs – the way that pain could be understood as purpose; the tradition of having their partners cut the umbilical cord; to hold their babies close, seconds after they come from you and smell, feel, and know that they in fact came from you; to feel hungry and to eat a dream post-delivery meal, for satiation not for survival; to smile at their baby more than they cried into its skin.

I lost out on what was yet to happen. My second pregnancy was full of insecurity. Instead of knowing better from experience, I only questioned more. Should I opt for a planned C-section, knowing that it still comes with heightened risks and complicated healing yet again? If I tried for a VBAC, would my body really have what it takes? Or would I just end up in the same trauma as the last? The odds for me, I was told, were literally 50-50. In either case, I wouldn’t have the confidence of “second births are often faster and easier.” My baby would never just “slip out” of me. My second delivery would ultimately be a decision based on fear rather than hope.

The worst of it all, I lost faith in myself and my body. I am repeatedly told it wasn’t my fault by my doctors, my therapist, my friends, my husband. But if not me, then whose fault was it? I needed someone or something to blame when I traced my fingers across the purple rubber of my keloid scar. Because my birth story, at its worst, made me feel that I didn’t prepare well enough. At its best, it assumes I did but failed.

***

Once you birth a child, their demands don’t wait for anyone or any body. Healing, therefore, isn’t a choice but necessary for survival. How one gets there is the question.

It is nearly a year-and-a-half later when I can look at my incision scar plainly. Sliced in haste, it’s jagged, dense in parts, crooked yet upturned, just like my motherhood origin story. My body now holds an ever-so-slightly tampered arrangement (twice over) of my uterus and all that cushioned the babies inside me. I often think, is healing not re-living shards of our memories and finding new ways to put it back together, until it vaguely resembles what it once was?

Every day I compare photos of the baby I don’t remember birthing to the photos of the son I have now. I think about the baby who was cut from me and the son who chooses to attach to me. I reconnect with parts of myself. I watch my hair cycle from loss to growth, I feel my body strengthen with each carry and caress, I notice subtle features in my son’s face that are only my own, I feel my skin warm when my beautiful boy calls out to me without hesitation: “Mama!” All of these signs that, yes, I am his mother. And slowly, gently, one day at a time, this is how I come to know – this body is a mother.

–

Reema Rao is a writer from Chicago. She most often writes fiction but also essays when her life compels something to say. Her work has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize and appears in Witness, The Los Angeles Review, and The Lipstick Politico, amongst other publications. In all of her writing, she is interested in moments of body transformation and how shame manifests in and around our bodies. She is a tired and proud mother to her two-year old son, three-month old daughter, and six-year old pup.